A procession of China’s Imperial Court in 1900 into the Palace in Beijing. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Throughout the first three decades of China’s reform period, the presentation of credentials by foreign ambassadors was a routine affair, hardly meriting special attention in the Chinese Communist Party’s flagship People’s Daily. This has changed dramatically in Xi Jinping’s New Era, as CMP noted in some detail our most recent monthly report on CCP discourse in cooperation with Sinocism.

Once consigned to the inside pages, such reports have risen to the front page, portraying Xi Jinping as a leader of imperial proportions, at the center of his diplomatic universe. Conscientiously constructed by party-state media, this image recalls the glorious dynastic past that Xi has so often invoked — when envoys, having traveled the Silk Road, would arrive in the capital to pay tribute to the emperor presiding over his court (万邦来朝).

Yesterday’s edition of the People’s Daily offered a glimpse of the reverse side of this same trend, the imperial treatment of Xi’s appointment of his own ambassadors.

Perhaps unnoticed by those who ignore the visual vocabulary of propaganda, the prominent treatment of diplomatic appointment news makes a simple but important point: that Xi Jinping’s centrality, significance and legitimacy as a national leader is bolstered by his genius as a commanding global leader.

Never in the time of Xi’s predecessors did announcements like that yesterday in the People’s Daily — of Xi’s appointment of new ambassadors to the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zimbabwe and Estonia — make it to the front page, much less to the “newspaper eye” (报眼), the space immediately to the right of the newspaper’s masthead. This coveted position has for decades been reserved (like the space below the masthead), for the most crucial of party news and announcements.

As a general point for observers of CCP discourse, such layout decisions in the People’s Daily and other official Party media are never incidental or aesthetic. They are intentional, and as such reflect decision-making and prioritization — being indispensable to how the Party speaks.

How have ambassadorial appointments been handled in the past?

When Diplomacy Was Just Diplomacy

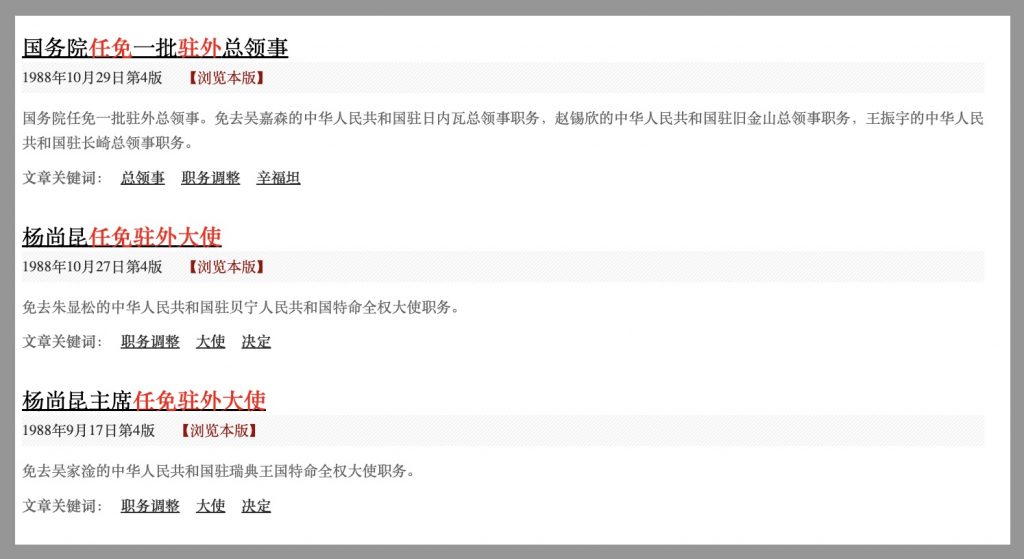

Turning back to the 1980s, we find that appointment news was routinely published on page four of the People’s Daily. In the image below, from the paper’s archives, you can see three such stories in September and October 1988, reporting appointments at the time by Yang Shangkun (杨尚昆), who had been appointed as president (国家主席) of the PRC that same year. All of these announcements are published on page four.

Moving on to the 1990s, we find that the same pattern prevailed still, with the notable difference that appointments were made by the top leader, Jiang Zemin, in his capacity as head of state, a position that from 1993 onward was held by the CCP general secretary.

Layout decisions in the People’s Daily and other official Party media are never incidental or aesthetic.

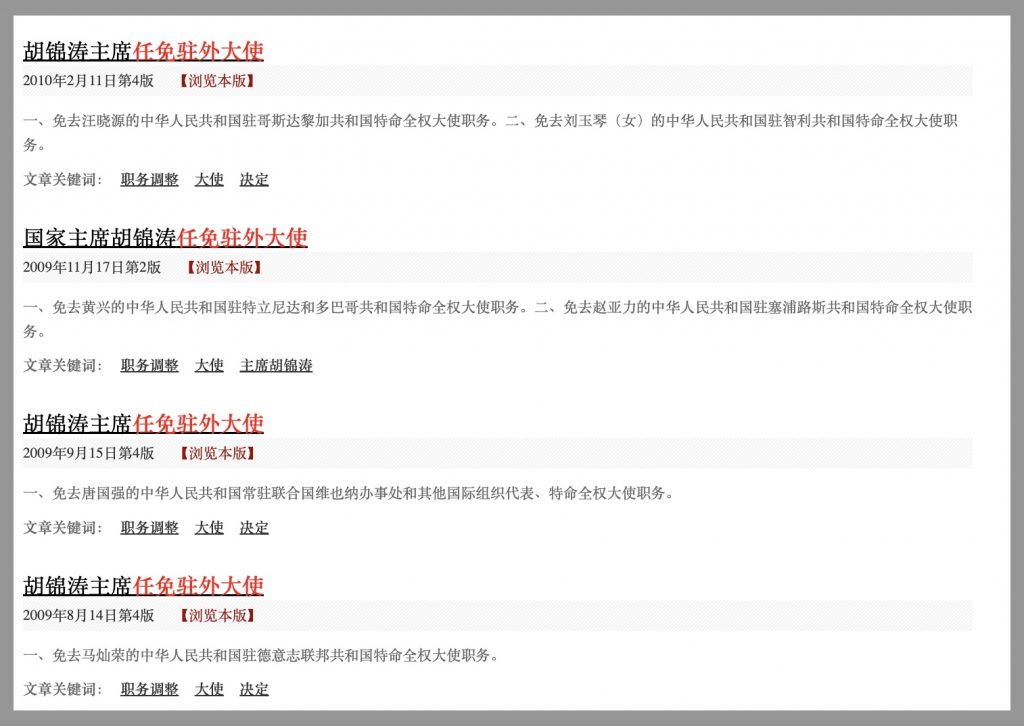

With just a few exceptions in the Hu Jintao era, this treatment of appointments in the People’s Daily remained consistent.

Such notices were never front-page news. Page four, certainly. Page two, possibly.

In 2013 and 2014, the first two full years of Xi Jinping’s rule, the old pattern persisted. In the archived articles below, you can see that ambassadorial appointments were published consistently on page three.

Bronze Mirrors for Xi

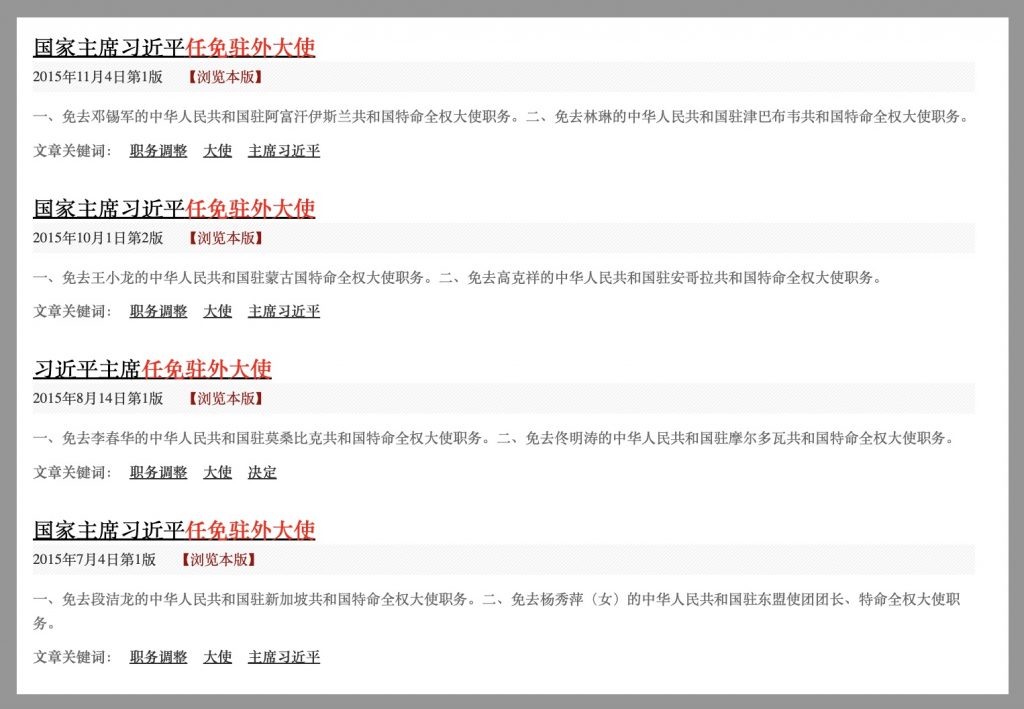

In 2015, common practice suddenly changed. When Xi made appointments of Chinese ambassadors to countries like Moldova, Mongolia, Afghanistan, and Singapore, these announcements appeared almost uniformly on page one of the People’s Daily.

By 2017, with the approach of the 19th National Congress and Xi’s second term in office, there were no longer exceptions to the front-page rule. Xi Jinping’s appointments were sometimes pushed out of the most coveted spots — by news of foreign visits and so on — but they were always among the top few stories.

From 2017 onward the elevation of appointment announcements continued in the People’s Daily.

Though a matter of educated speculation, it is likely that the prominent treatment of Xi’s diplomatic centrality was from the beginning about harnessing China’s international ambitions under Xi — seen in the trashing of Deng’s long-held bide-our-time policy — to further rationalize his personal grab for power.

In 2018, particularly, as the CCP scrapped presidential term limits, privately a profound concern to many within the Party, the need to manufacture sources of legitimacy was keen. By 2021 and 2022, it was not uncommon to spot announcements in the “newspaper eye,” such as this page (right) from May 13, 2021.

The sense in the official state media that Xi is holding audiences at court has been accentuated in recent years with pomp and symbolism on the ground as well. When French President Emmanuel Macron made an official visit to China in back in April, the symbolism at times reached absurd proportions. At one point after Macron’s arrival, the two were pictured standing stiffly at attention on an elevated red stage along the course of the red carpet, under a red pavilion with gold tassels and glistening gold railing. As Chris Patten, the last British governor of Hong Kong and a former EU commissioner for external affairs, noted, “[even] Macron himself seemed slightly embarrassed by the pageantry.”

Considering the imperial point Xi Jinping was trying to make, of course, none of these flourishes were too extravagant or too outlandish. Visually, as politically, the general secretary must be enlarged.