When two men arrived outside the gates of a coal processing enterprise in the city of Zhengzhou back in May this year and began filming video, the company’s boss demanded to know their business. The men explained that they were journalists from Henan Economic News (河南经济报), and that they were documenting his company’s failure to comply with environmental standards.

From there, the conversation moved quickly beyond the facts of their planned report to a more practical question — how the company could make it disappear.

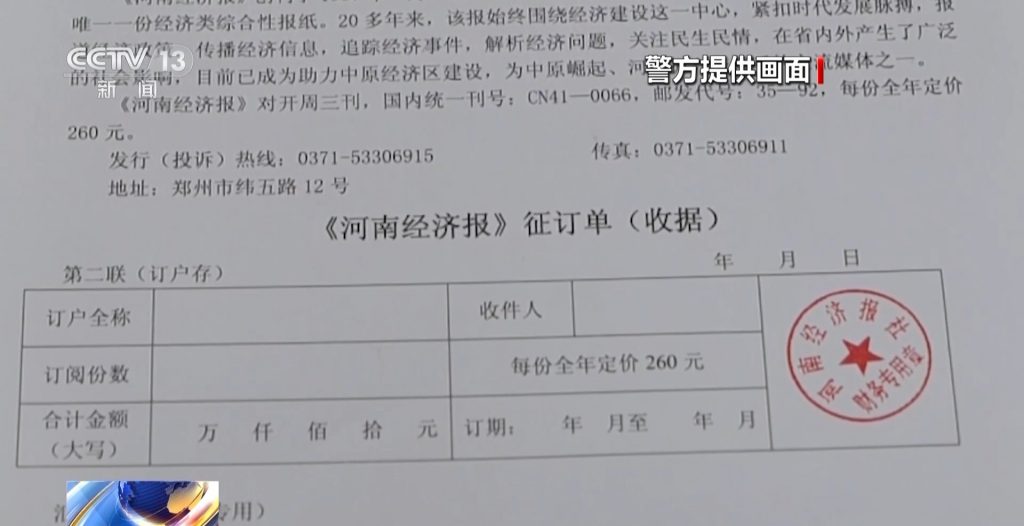

If the boss wished not to have his company’s violations reported publicly, a simple arrangement was possible. For 12,000 yuan (about 1,600 dollars) transferred directly to a designated account, the journalists could shelve the report. The transaction would be disguised as a payment for a company subscription to Henan Economic News. The men could even provide an invoice bearing the media outlet’s official stamp.

Understanding the adverse impact a news report might have on his company, the boss readily agreed and processed the transfer. Only months later, as police in Zhengzhou pried open the lid on other cons committed by the two men, would the boss come to realize that they were not in fact journalists at all.

The Big Business of “News Extortion”

The “gag fee” (封口费) offered by the Zhengzhou company in exchange for silence was just one of many documented examples this year of a practice known as “news extortion,” or xinwen qiaozha (新闻敲诈). In a special report aired earlier this month, the state-run China Central Television highlighted this and other cases, reporting that since early this year police across the country have launched a special operation to “strike fakes [and] stop extortion” (打假治敲).

In fact, news extortion has persisted in China, ugly and stubborn, since the rise of the commercialized media industry in the mid-1990s. The idea behind the practice is frightfully simple, and the practice frightfully common, though cases are rarely reported in China’s media and the true scale of the problem is unknown. Essentially, media dangle the threat of negative revelations in front of a company or individual before presenting paid-for silence as an alternative path.

In fact, news extortion has persisted in China, ugly and stubborn, since the rise of the commercialized media industry in the mid-1990s.

The question of who exactly these media are — who is real, who is fake, and why this distinction is meaningful at all — is a complicated one, going to the heart of how China regulates and controls the press. But despite decades of official attention to news extortion, including regular government campaigns and notices (some lumping the practice together with “critical reporting”), cases are by all accounts staggeringly commonplace.

Over the past few months, local governments from the cities of Heihe and Zhaodong in the north, close to the Russian border, to Zhoukou in the central province of Henan, down to Yunnan in the country’s southwest, have all issued various statements, campaigns or cases involving news extortion. This year and last, the China Association for Public Companies (中国上市公司协会) warned listed companies to be alert to the practice, even dealing with the issue in a closed-door session in April with senior propaganda officials.

Shortly after the airing of the CCTV report this month, police in Chongqing reported that they had uncovered two cases since August, both involving legally registered culture and media companies that had launched unauthorized news websites — Chongqing Reports Online (重庆报道网) and China Digital News (中国数字报).

Local authorities warned the public to remain alert to the “three press fakes” (新闻三假), including “fake media” (假媒体), “fake reporting stations” (假记者站), and “fake journalists” (假记者), and said that “news extortion not only infringes on the interests of the public and interferes with order at the grass-roots level, but also undermines the standardized and orderly press and public opinion environment, which is very harmful.”

Given the fact that China’s ruling Communist Party maintains stringent controls over the press in every conceivable form, the obvious question raised by this stream of fraud and fakery is: Why?

Serving Power and Profit

To its credit, the special report this month on CCTV did raise the question, though in a way that seemed almost baffled and plaintive: “Why, still, are there people who run the risks and constantly step over the red line?”

Sit back, CCTV.

The simple and obvious answer, which China’s leadership is unable to concede, is that it has created the conditions for media corruption by making power the only standard of truth that truly matters. Crooks and crooked reporters, whether they hold valid press cards or not, understand that their power as journalists arises not from their ability to expose the facts to the public, but from their share, real or perceived, of state power. They thrive commercially on the threat of journalism as a function of state power — and on the promise of silence on the flip side.

The practice of news extortion, and all other forms of media corruption, is quietly and insistently reinforced by the calculus at the heart of state-led journalism. As a matter of Party practice and doctrine, media in China are not agents of transparency and accountability, with their own reserves of hard-earned credibility, but rather servants of the ruling Party’s truth. This means facts and revelations must constantly be buried in the push to “emphasize positive news” and “tell China’s story well.”

The practice of news extortion, and all other forms of media corruption, is quietly and insistently reinforced by the calculus at the heart of state-led journalism.

In this sense, China’s entire commercialized media sector, which is tied directly to Party and government institutions, operates on a gag-fee principle so all-embracing that it remains generally unseen. The deal is this: Do the bidding of the leadership, keeping negative news under wraps as you praise its positives, and you will be allowed to profit and prosper. The government will license your media, and issue press cards to your reporters.

When media serve power rather than hold it to account, it stands to reason that they are vulnerable to the same distortions and excesses as unaccountable power. There are, moreover, no independent professional mechanisms to hold media to the highest standards, precisely because power defines the parameters of professionalism. The Party’s tight grip invites loose professional standards. Within media that are licensed — and therefore legitimate in the eyes of the state — journalists will see the false dealing behind the scenes, and understand the ultimate pointlessness (and even danger) of reporting the truth. Meanwhile, outside the formal media scene, or proximate to it, unscrupulous characters will rightly see how media power translates into commercial gain.

This is the secret behind the persistence of news extortion and other forms of media corruption in China — and the answer to CCTV’s question.

The Lie of the Fake

Is it the answer CCTV offered to its viewers? Of course not. China’s authorities and state media are trapped in an endless loop when it comes to explaining and combatting media corruption because understanding the real root causes would mean doing what they cannot — confronting thorny questions of institutional power head-on.

Instead, the perennial focus when questions of media corruption arise is on those instances of outright fakery that happen outside formal and accepted media. These cases support the necessary thesis that the root problem is the “fake” journalist, media, or reporting station, which reinforces the Party-state as the locus of the genuine.

Despite this framing, the uncomfortable truth is that Party-run media have historically been among the worst offenders when it comes to cases of media corruption, including news extortion. Such cases rarely come to light, for reasons that should be obvious. But the handful of examples we do have are outstanding. There is the 2007 court case prosecuting the many sins of Meng Huaihu (孟怀虎), the Zhejiang bureau chief for China Commercial Times — a Beijing-based business paper published by the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce (ACFIC). There is the 2008 cover-up of a mining disaster in Shanxi after journalists from scores from official media, and several imposters too, accepted pay-offs from the mine boss.

The most famous, and perhaps most egregious, media corruption case was uncovered more than two decades ago, in July 2002, when China Youth Daily reporter Liu Chang (刘畅) found that eleven reporters, including four from the government’s official Xinhua News Agency, had accepted gag fees (including cash and gold nuggets) to cover up news about an explosion in which 37 workers had died, their bodies stuffed away into a mine shaft while family members were forcibly detained.

It is no accident that these cases, which received rare attention in the nationwide media, all pre-date Xi Jinping’s “New Era,” emerging at a time when journalists like Liu Chang (who faced harsh internal pressure over his story) could manage to find space, despite controls, to pursue their own professional ideals. That space has contracted rapidly over the past decade amid renewed political controls on the media, and an overbearing emphasis on uplifting propaganda, or what Xi Jinping calls “positive energy.”

Concerns today over news extortion and the need to maintain an “orderly press and public opinion environment” focus on the depredations of imposters outside the system — which brings us back to the perpetrators of the con mentioned at the start of this story.

Not only had the two men presented themselves as reporters from a genuine newspaper in Henan, but they had also, in order to bamboozle other companies, created an online outlet called Mirror News (镜相新闻) through a locally registered culture and media company that kept its offices in a well-known Zhengzhou media complex. Using Mirror News as a front, the men had managed to secure a “news fee” (新闻费) of 130,000 yuan, about 18,000 dollars, from yet another Zhengzhou coal processing enterprise.

This time the process started with a negative report on the company published online, which was then amplified through social media channels until it got the attention of that company’s boss. The men followed up with a visit, identifying themselves as journalists for Mirror News, and this time claimed they could work behind the scenes, given their media connections, to ensure that the original story was taken down, and related social media posts expunged. Beyond these services, they said, they could offer ongoing protection against negative press.

The company boss agreed to the arrangement and was only tipped off that something was awry when he noticed that the negative posts remained online as the weeks passed.

But the account broadcast this month by CCTV revealed another important clue. In fact, the network reported, the boss had initially been skeptical of the two men in his office. He had never heard of Mirror News. The tricksters, of course, had another card up their sleeve to coax the boss past his skepticism. They told him that Mirror News was associated with The Paper (澎湃新闻), a Party-run digital news outlet operated by the powerful Shanghai United Media Group.

CCTV reported: “As these two men name-dropped a well-known media outlet to trick him and earn his confidence, and as he urgently wanted to remove these online posts . . . . the boss agreed to what the men proposed.”

Apparently, the boss’s instincts about the two men and this unfamiliar outlet Mirror News had been spot on. The imagined association with The Paper, however, changed his mind.

Real power can have that effect on people.