As the news broke internationally last Friday of the death of former Chinese Premier Li Keqiang (李克强), one word in the headlines seemed to condense the political significance of his passing. That word was “sidelined.”

Many outlets told the story of a determined reformer, a “moderate technocrat,” who within the torrid climate of Xi Jinping’s political rise had been increasingly marginalized — left out on the cold frontier of pragmatism as the country’s new emperor showered himself with glory, and surrounded himself with the kind of yes-men Li was not.

When it comes to Li’s exposure in the official Party-state media, a preponderance of evidence supports this basic storyline.

Li’s marginalization within the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) was often salient as we compiled our regular monthly reports on official discourse in the CCP’s flagship People’s Daily newspaper through to March this year, by which time the outgoing premier merited barely a whisper. Most months for more than two years running, Li Keqiang logged a meager 30 or so articles to Xi Jinping’s imperial 700-plus-or-minus. And while no one in the PSC could touch Xi’s numbers, it was often the case that Li, though nominally number two, trailed behind his closest peers.

Even when he was compellingly human, like that time in August 2020 when he trudged knee-deep through clay-colored floodwaters in Chongqing, Li Keqiang could not turn the spotlight from his immaculate superior, something we looked at more closely in “Li Keqiang in the Muck.”

In death, it seems, Li Keqiang has been sidelined too.

Commonplace Superlatives

As is typical in China, where the deaths of Communist Party officials are never personal but must be properly filed within a careful pecking order of prevailing political calculations, the leadership honored Li over the weekend with straight-from-the-box superlatives.

Li’s life had been “a life of revolution, a life of struggle, a life of glory, a life of serving the people wholeheartedly, a life dedicated to the cause of communism,” it said, words that might have been lifted directly from the June 2007 obituary of Huang Ju (黄菊), a Politburo Standing Committee member who passed before completing his term as first-ranked vice premier.

Li had been “an outstanding proletarian revolutionary and politician, and an outstanding leader of the Party and the State,” the text added — language perfectly mirroring that following the June 2015 death of Qiao Shi (乔石), and the July 2019 death of Li Peng (李鹏) — before adding the terse details of his death. In Shanghai. Ten minutes past midnight on October 27, owing to “a sudden heart attack.”

Who was at his bedside? What grieving family members are now left behind?

Such earthy and human details can never be included in the CCP’s formal accounts of death. They would distract from the Party’s unassailable centrality. Instead, Li the faithful servant is treated as though the ruling Party was the pulsing center of every act of love he ever made, that “from the time he was a teenager, he loved the Party, loved the motherland, and loved the people.” (This is identical language, mind you, to that marshaled for the death last year of Yuan Longping, the Chinese agronomist and inventor celebrated for first developing hybrid rice varieties.)

In the People’s Daily, the treatment was predictable. Li’s official obituary was published as expected on October 28, the day after his death, and it was handled exactly as the July 2019 obituary for Li Peng, also at the time a former premier.

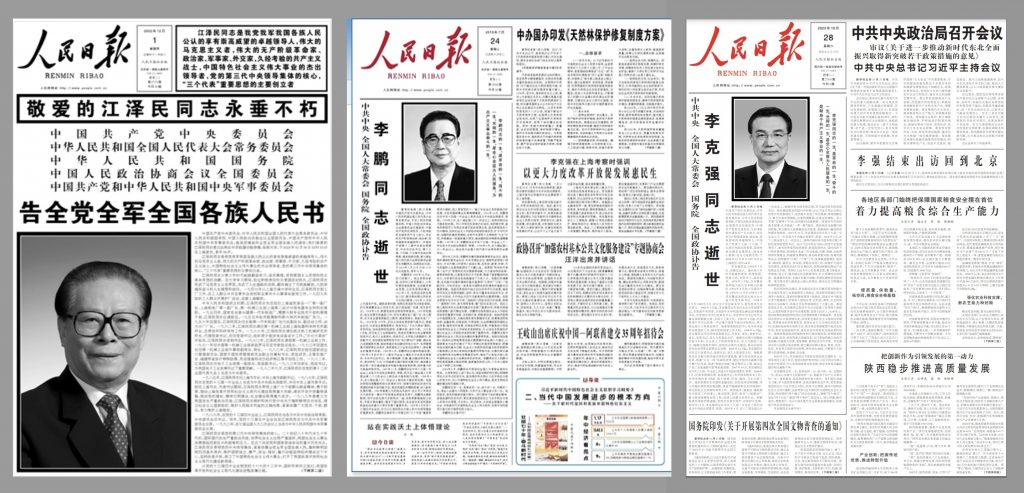

Looking at the three front pages for the obituaries of former top leader Jiang Zemin (江泽民), Li Peng, and finally Li Keqiang, we can see clearly that Jiang — like Deng Xiaoping before him — is given marquee treatment. The entire page for Jiang goes black, including the bright-red People’s Daily masthead.

What was done for Jiang would of course not be done for Li Keqiang, very much his junior in status. Like Li Peng, Li Keqiang is put in his proper place and filed away with the proper honorifics.

A Quick Burial for the News Cycle

But even as it remained in keeping with the Party’s terse traditions, Li Keqiang’s paint-by-number treatment in the official Party-state media, including the brief initial announcement on the 27th and the official obituary on the 28th, closely mirrored the former premier’s sidelining by the leadership under Xi Jinping. This likely reflects plans at the top to ensure that Li’s death can be made to pass swiftly, with due respect and properly stage-managed solemnity.

Xi and his acolytes surely hope that all possible political inferences stemming from Li’s death can be quickly buried, particularly as they might relate to and intersect with questions of economic governance — and, for many Chinese, real economic pain.

Through the day on October 27, the day of Li’s death, mentions in the state media were downplayed, and sometimes not at all visible. The image to the left shows the homepage of People’s Daily Online, a site majority controlled by the flagship People’s Daily newspaper. The headline about Li’s death (highlighted) is literally sidelined — placed to the right, below a massive headline about the city of Wuhan as a hub for high-tech development, and a smaller headline about Xi Jinping meeting with California Governor Gavin Newsom.

Below the homepage image is a screenshot of the full text of the terse announcement of Li’s passing, ending with a note that his “obituary is forthcoming.” For more than 24 hours, this official Xinhua News Agency release was the only word on Li at all, an unsatisfying place-holder.

On Xinhua’s own news portal, the story was similarly shoved to the side, not appearing in the featured slideshow or in the prominent top headline.

The top story at Xinhua was again about Xi’s meeting with California’s Newsom, and in second place, just above the clipped Li Keqiang headline, was a story about the publication of yet another collection of Xi’s remarks on a policy issue, this time “civil affairs work” (民政工作).

Even this tinder-dry news might easily have been linked to Li’s time in office — but the intention is to quickly move past the story, not to plumb it for its deeper significance. In a Chinese political context, there is always a great deal of forgetting in every act of remembrance.

In a Chinese political context, there is always a great deal of forgetting in every act of remembrance.

Even more striking, however, was the way Li Keqiang’s fuller obituary the next day was shoved right out of the news on many prominent websites despite the undeniable newsiness of the news.

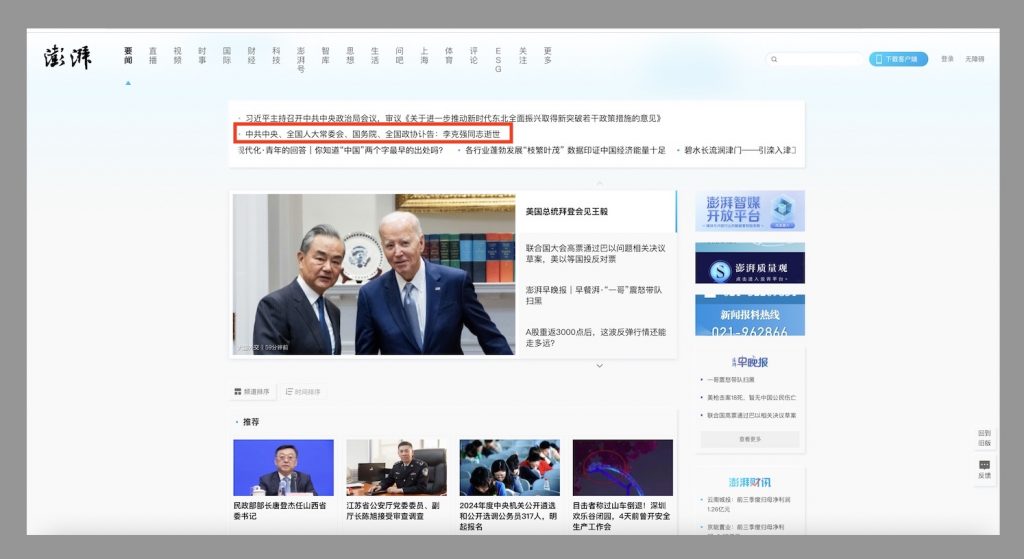

Neither Xinhua nor Shanghai’s The Paper (澎湃新聞), a relatively popular digital news outlet under the state-owned Shanghai United Media Group, played news of Li’s death in a prominent position. The top story instead was the most recent meeting of the CCP Politburo, led by Xi Jinping to discuss the revitalization of China’s northeast. Also in a prominent position on the site, the first story appearing in the featured slideshow of top news, was the Xinhua report of the meeting between US President Joe Biden and China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi (王毅) in Washington.

The Paper ran its mention of the Li Keqiang obituary just below the headline about the Politburo meeting but with no visual presence for the departed former premier. Visually, the focus was on Wang Yi and Jo Biden.

At websites and on social media in particular, the strategy was to draw attention away from Li Keqiang, because conversation and commentary are more liable in these more interactive channels to develop in unpredictable ways — the same way things have unfolded offline as ordinary Chinese have expressed their heartfelt (and often subtext-laden) condolences to Li, voiced their hunger for justice, and sometimes dissolved with palpable grief.

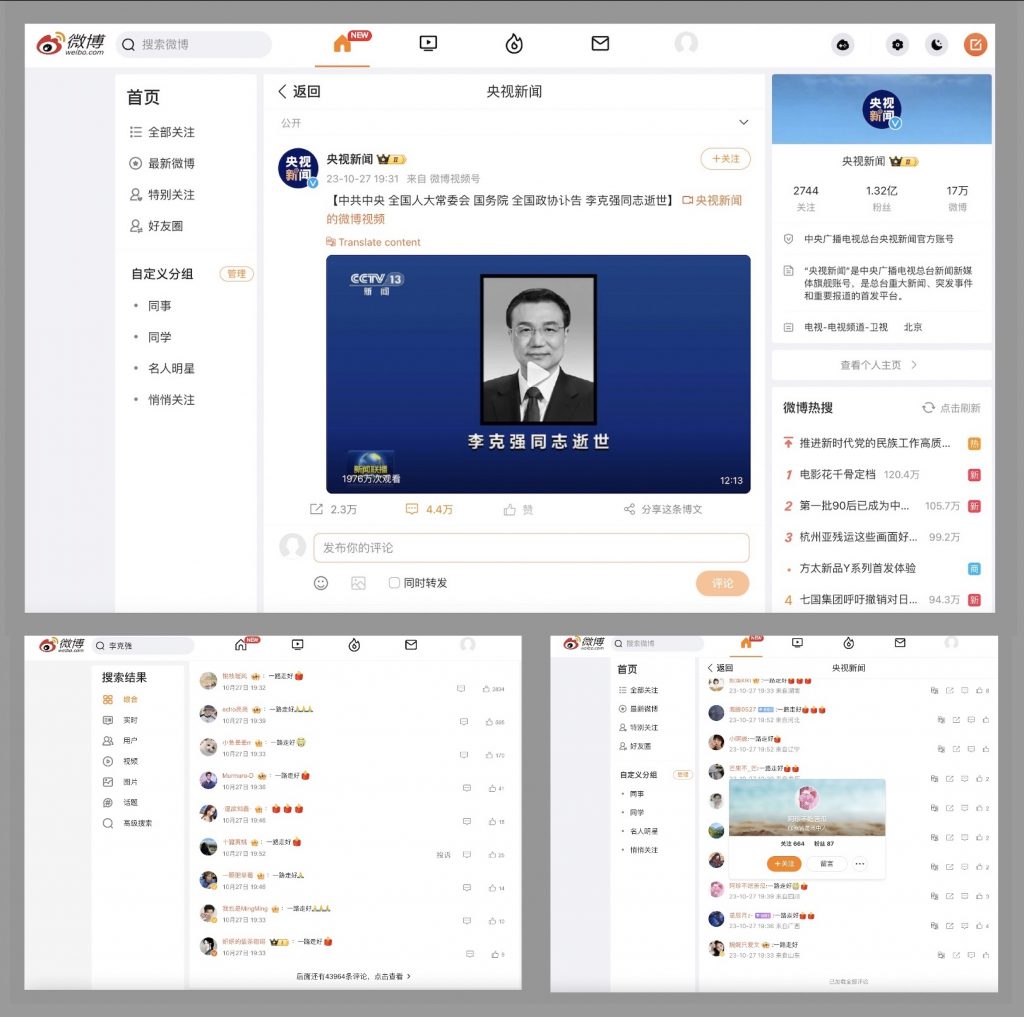

The hot topics list on the social media platform Weibo on Saturday, the day of Li’s death, was unaccountably topped by news of the Politburo meeting, which was displayed as “hot” — almost certainly through artificial promotion. A slate of social stories and entertainment scandals followed, including the case of “Crazy Little Yang” (疯狂小杨哥), an online influencer and founder of the Three Sheep Network who reportedly shocked some internet users recently with his vulgar language and behavior online. Number three, according to the list, was a Xinhua News Agency retrospective on the country’s space program.

The thread on Li Keqiang, leading again only to the terse announcement of the former premier’s death and pending obituary, was toward the bottom at number nine on the list. Chinese, it would seem on the basis of this hot list, are so focused on the stars above and the influencers down below that they have little interest in the passing of a popular senior official. But this of course is social media engineering at work, what the cyberspace authorities in China call “public opinion channeling” (舆论引导).

The search results on Sunday for “Li Keqiang” on Weibo were another illustration of the effort to encourage ceremony over real emotion and remembrance. The top results were all from major official Party-state media, including Xinhua News Agency and China Central Television, and all shared the brief initial announcement. For these state media Weibo posts, however, the comments were strangely unexpressive for a comment culture that can often be extraordinarily clever.

Under a top post by the state-run CCTV, the numbers said that more than 44,000 users had already commented. The only words posted to successive pages of comments, however, were “Wishing you well on your journey” (一路走好), a common phrase with which to bid farewell to those who have passed on.

These uniform comments, differing only in the number of burning candle emoticons typed to one side, were a transparent ruse.

The search results on Sunday for “Li Keqiang” on Weibo were another illustration of the effort to encourage ceremony over real emotion and remembrance.

Posts below those of central state media were largely from foreign embassies in Beijing, likely promoted because they dealt with foreign relations rather than more delicate domestic issues.

These posts differed refreshingly — at least, in terms of detail — from those of the state media. The Embassy of the United Kingdom, for example, highlighted Li’s audience with Queen Elizabeth in 2014. “Li will be remembered for his contribution to the people of China and his contribution to strengthening the bilateral relationship between the UK and China,” the post read.

The comments under these posts were also more varied, their relative diversity reiterating the falseness of the homogenous comment threads under the posts from state media. They seemed to enjoy slightly greater latitude, possibly because the authorities and Weibo enforcers were a tinge more sensitive to the fact that these accounts were overseen by foreign missions. “The scale in the hearts of the people is the fairest of all,” said one comment, an oblique reference to the respect many Chinese feel for Li Keqiang as a leader who, from time to time, could surprise with his frankness on issues such as poverty that matter to the people.

Others were more direct, even criticizing the official handling of Li’s death. “Finally, someone is posting condolences and remembrances. In the domestic media, aside from repostings of the [official] obituary, there are no memorial videos or articles,” said one post on October 28.

As the leadership hurries grief behind the curtain, this act of dismissal has not gone unnoticed, a reminder of the perils on the flip side of control. The above comments, and many others, went tiptoeing to the heart of the issue: the fact that the country’s authoritarian Party regime (of which, it bears reminding, Li Keqiang was very much a part) cannot allow the public to open their hearts, except in ways that are scripted and unhuman.

For the Chinese Communist Party, every official death is a moment of ceremony, and a reminder of power, stripped of its humanity. Unfortunately, for the leadership, the acknowledgment of death is something deeply and viscerally human, and its intersection with memory is ineradicable. At such times, as the insistent memorials online and offline make clear, human beings require words and acts that pulse with life — and silences that are meaningful.

“At last,” said another Chinese comment after the UK embassy remembrance, with what seemed an immense sigh of relief, “a post that speaks a human language.”