A rescue worker searches through the rubble of Japan’s 2011 earthquake. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

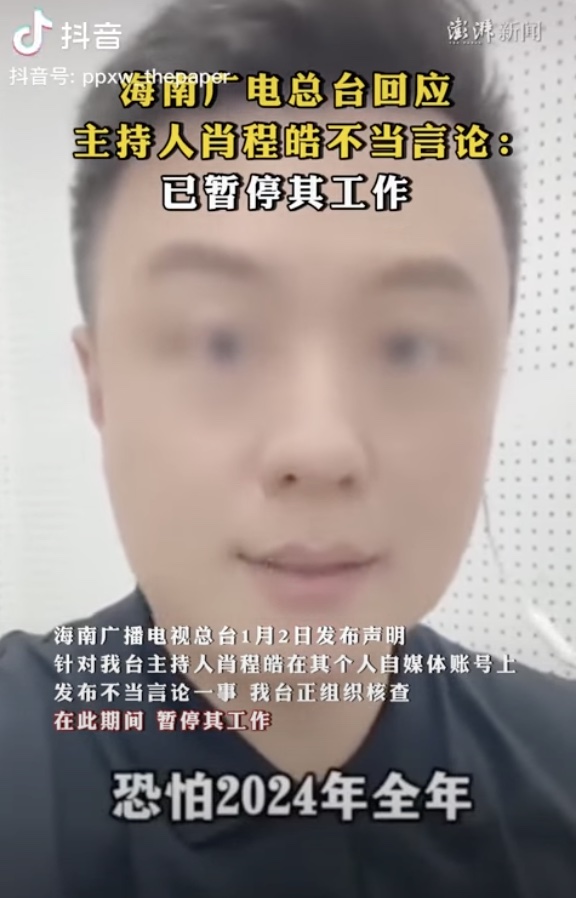

Last week in China, a state-run Chinese media outlet fell victim to the state’s own efforts to ramp up anti-Japanese sentiment. In response to a devastating earthquake in Japan’s Ishikawa Prefecture, Hainan Satellite TV (海南衛視) host Xiao Chenghao (蕭程皓) posted a video that asked, “Has Retribution Arrived?” (報應來了?)

“For such a strong earthquake to strike Japan may seem really unforeseen,” said Xiao, immediately before suggesting the temblor was directly linked to Japan’s controversial dumping into the Pacific Ocean last August of treated wastewater from the Fukushima nuclear plant. “But for such a major natural disaster to occur on the first day of the new year . . . It seems there are certain actions that should be minimized. Nuclear wastewater should not be released into the sea.”

It was the latest in a pattern of schadenfreude that rears its ugly head whenever natural disaster strikes Japan. Anti-Japanese sentiment has been more pronounced in China since last year, when state media launched a disinformation campaign on the supposed environmental damage caused by Japan’s actions (deemed harmless by UN regulators).

Although many netizens expressed concern for the hundreds dead or missing after the magnitude-7.6 quake, the idea that they deserved their fate was widespread.

In Xiao’s case, however, his employer tried to take the high road. The broadcaster announced it was suspending Xiao for “inappropriate” behavior. This caused a furore online — many believed Xiao had a right to be vocal given Japan’s historic (and supposed current) crimes. “We have been bullied and insulted so much,” a commenter wrote, “what does it matter if we say that retribution has arrived?” One netizen even reported the network’s director to the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI).

Beijing’s official line has been more dignified, offering condolences to the victims. Even nationalist firebrand Hu Xijin posted on Weibo that Xiao had caused “damage” to Hainan Satellite TV’s image. That said, Hu did not condemn anti-Japanese sentiment — he maintained that ordinary citizens were free to “applaud” the disaster if they wished, but urged public figures to “keep a distance.”

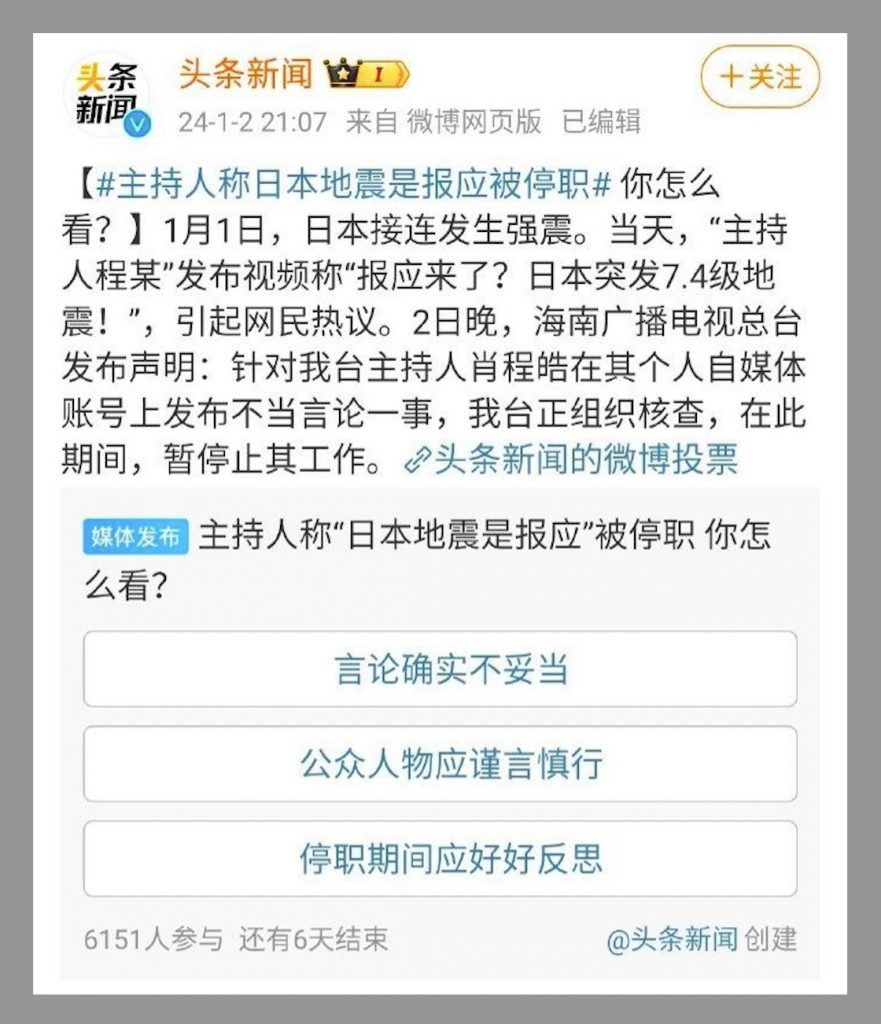

Other media opted to educate the public in a less subtle way. In a Weibo public opinion poll, where Toutiao asked the public for their thoughts on the suspension, the only options were various forms of agreement.

It’s possible giving netizens the option of expressing hatred for the Japanese could risk demonstrating how prevalent such sentiment is, or expose the outlet to accusations of stirring up such hatred.

With Xi Jinping calling on China’s state media to make the country appear more “lovable” (可愛) to the outside world, at least some realize that gloating over the deaths of innocent foreigners is not a good look.