In early February, Chinese media teemed with stories of cultural festivities in rural villages countrywide. In a “rural bookroom” in Xinjiang’s Ha’ermodun Village, a series of events “enriched the spiritual lives of villagers,” according to a local news release. More than 4,000 kilometers away, in Fujian’s Shuqiao Village, residents held a “Rural Spring Festival Gala” featuring song and dance performances. Down south, in a remote corner of Hunan province, more than 50 residents gathered for a “village lecture.”

These and thousands of similar events across China’s vast rural hinterland are part of a concerted push to achieve what the Chinese Communist Party leadership has called the “revitalization of rural culture” — and at first glance, the ambitious policy seems to offer an unprecedented level of cultural access at the grassroots.

Take, for example, the country’s growing network of rural bookrooms (农家书屋). First introduced as a pilot project in 2005, rural bookroom growth boomed through the 2010s, their numbers soaring past 580,000 nationwide by the end of 2021. For perspective, those numbers translate to 428 rural bookrooms on average in each of China’s 1,355 counties. Given these astonishing numbers, one might assume the rapid development of rural bookrooms has put literature in the hands of millions.

The full picture, however, is far more complicated. In fact, the drive to foster cultural enrichment at the grassroots is part of a broader effort by the CCP to tighten its grip on society, echoing the rural-based political movements of the Party’s past.

Accelerating since late last year under the notion of “Xi Jinping Thought on Culture” (习近平文化思想), China’s “revitalization of rural culture” (乡村文化振兴) is not a cultural rebirth but a red renaissance. And a more careful reading of China’s reporting on the policy hints at record levels of cultural waste.

Lessons in Gratitude

Early this year, the countryside revitalization program was given a further boost with the joint release of a work plan on cultural revitalization by two government departments, responding to a related high-level policy released in January.

Defining the basic terms of cultural work, the plan — called “The Countryside Flows with Color” (大地流彩) — began with the insistence that all activities “adhere to correct guidance” (坚持正确导向), a clear reference to the link between cultural control and political stability. While it called for “rich and diverse countryside cultural events” by designating 12 “key activities” (重点活动), the first activity made clear from the outset that programs must serve the political bottom line. There were to be public lectures across the country on the topic of “listening to the Party, having gratitude for the Party, and following the Party.”

China’s “revitalization of rural culture” (乡村文化振兴) is not a cultural renaissance but a red revival.

The plan also called for poetry, drawing on the enduring cultural motif of the hometown (家乡). But politics intruded once again. Rural poetry readings would adhere to the theme, “Love China, Love Your Hometown” (爱中华爱家乡), for which participants would be encouraged to “pay tribute to the Motherland, eulogize the Era, and praise their hometowns.”

Sandwiched in the middle of this cultural call, “eulogize the Era” was an unmistakable reference to Xi Jinping’s notion of his leadership as a “New Era” (新时代), a period of political renaissance. The notion of the Chinese “motherland” (祖国), too, is a common stand-in for the Party-state, emphasizing the CCP’s role as the protector and guarantor of prosperity.

The government’s cultural work plan is full of such acts of replacement, ensuring that the notion of cultural renaissance is braided tightly together with the Party, its legitimacy, and its power.

But is it not possible, despite the obvious political overtones, that the net result of the push to build cultural infrastructure in the countryside could be more widespread cultural access? What about those nearly 600,000 rural bookrooms?

Reading Between the Party Lines

Before we picture villagers huddled up with copies of Lu Xun’s stories, or collections of Tang dynasty poetry, it is best to look more closely at how the local governments and the Party-state media describe the purpose of these rural bookrooms.

Returning to Xinjiang’s Ha’ermodun Village, reports from county authorities referred to the local bookroom in 2023 as a “filling station” where CCP members and cadres could go to recharge on the “spirit” of the CCP’s 20th National Congress. A course taught in the space by a lecturer was devoted to the same topic, noting the importance of informing villagers about the latest political directives from the central leadership.

While rural bookrooms like that in Ha’ermodun have often been advertised as a way of encouraging “reading for all” (全民阅读), political themes are always at the forefront. In many official news stories, they are referred to as “red bookrooms” (红色书屋), an unofficial moniker that makes their political function even clearer. They have also been called “classrooms for Party history” — teaching rural people how they owe thanks to the Party for their “hard-won happy lives,” and how prosperity will continue so long as they “continue walking with the Party.”

“These little red bookrooms,” as the official People’s Daily put it in a report on remote Qinghai province, “have taken up the important task of fostering closer ties between Party cadres and the masses.”

The politicization of cultural pastimes is likely a key reason for the low level of response from village residents. In June 2018, the China Youth Daily, a newspaper published by the Chinese Communist Youth League, warned that rural bookrooms ran the risk of becoming mere “image projects” (形象工程), a term often applied to empty or superficial endeavors meant to please government superiors — and in many cases, to skim public resources. Without real efforts to ensure quality, the paper said, it would remain “very difficult to attract villagers to visit [local bookrooms].”

Six years on, the results are scarcely more encouraging. As the push for the “revitalization of rural culture” has become a political necessity, with pressure from the top, the establishment of rural bookrooms has continued apace. In April last year, Zhejiang province boasted in a report on rural development that by the end of 2022 it had built more than 25,000 rural bookrooms, covering each and every one of the province’s administrative villages.

Is a revolution in literacy on the horizon? Hardly.

A Flood of Cultural Waste

In March this year, a new work directive from the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), the Party’s top anti-corruption body, named rural bookrooms among the initiatives being routinely abused as “new image projects” by local officials, wasting public resources “under the guise of working for the good of the people.”

As a new campaign against formalism and corruption took hold, the official Anhui Daily newspaper reported last month — with a fresh sense of consternation — that one local jurisdiction in the province had rapidly constructed more than 600 rural bookrooms to “keep pace with the trend,” with virtually no visits from villagers recorded by the end of the year. The report confessed that waste had been fueled by campaign-style governance as higher-ups pressured local officials to meet quotas for the sake of political point-making.

“Formalism has emerged at the grassroots, but it is not quite true to say that the responsibility lies entirely with the grassroots,” the paper said.

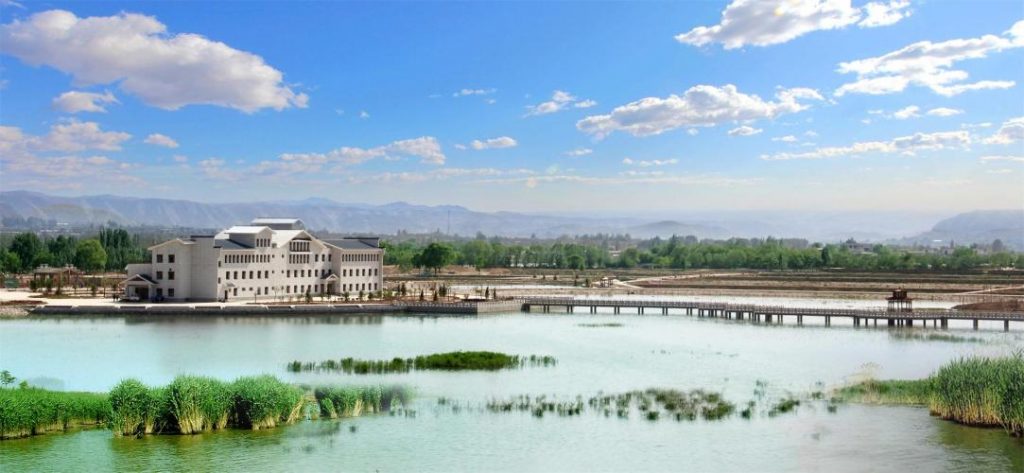

These problems extend beyond the country’s hundreds of thousands of rural bookrooms, according to the CCDI directive. It also cited the waste of public resources caused by the runaway construction in rural areas of “culture and sports centers for the masses” (群众文体馆), and the building of wetland parks at exorbitant costs in local areas suffering from water shortages.

Wetlands and man-made lakes, which have been rationalized over the past decade as potential tourist attractions (often a key priority in cultural development), are an example of just how broad, and how unbridled, the push for rural cultural development has become.

In 2021, environmental inspection teams in dryer areas of northern Henan province found numerous instances of local governments diverting scarce water resources from the Yellow River to create wetlands and lakes, justified as improving the natural landscape and creating a “beautiful countryside” (美丽乡村). Similar cases can be found across the country, including in far more arid Gansu, where in 2023 inspectors found that artificial lake and wetland projects in the fragile Heihe River basin had “exacerbated water resource tensions and increased the risk of ecological degradation.”

In a country where water has deep cultural significance, these projects are perhaps the most fitting metaphor for a cultural policy that has been pushed over the embankments by politics and power-brokering. As the top-down drive for cultural development has become an urgent political prerogative, a flood of wasteful and ineffectual cultural projects has been the natural result.

China’s leadership is responding the only way it seems to know how — with another top-down campaign to restrain what it unleashed. And as the push for the “revitalization of rural culture” persists on the one hand, and the campaign to curb its worst excesses advances on the other, the farthest thing from anyone’s mind will be real cultural empowerment.

David Bandurski