These days, the death of a newspaper is hardly, well, news. In China, as in much of the rest of the world, information consumers long ago turned toward fresh digital alternatives, including social media and news apps. The country’s latest report on internet use last year showed that it had more than one billion internet users, of which nearly 98 percent used online video services — now one of the most popular sources of content.

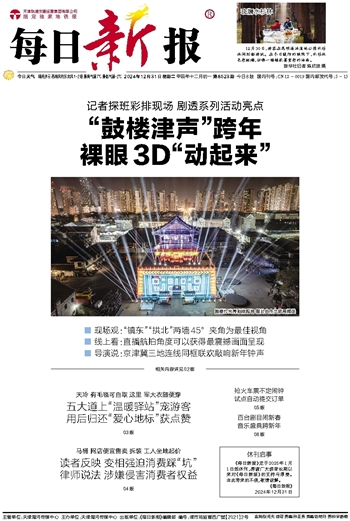

Mostly outside the headlines last month, the disappearance of print offerings in China’s media continued. Among the publications ceasing operations entirely was the Daily News (每日新报), a commercial newspaper launched a quarter century ago under the umbrella of Tianjin Daily (天津日报), the official mouthpiece of the Tianjin city leadership. The paper’s claim to fame back in December 2004, during the heyday of the metro newspaper in China, was to publish a single daily edition with 516 pages — a record at the time.

Joining the ranks of those that ceased publication (停刊) was Xijiang Metropolitan Daily (西江都市报), a paper based in the city of Wuzhou, in Guangxi, that was also launched in 2000. Like most commercial print publications in China, the paper was a spin-off of the local CCP-run outlet, in this case Wuzhou Daily (梧州日报). In many cases back in the halcyon days, as the advertising market soared on the back of breakneck economic growth, these “child papers” (子报) could provide the revenue stream to support their CCP parent publications. The bottom fell out of that market in the mid 2010s, with the emergence of powerful digital competitors like WeChat.

Also on the list of quiet exits was the Yunnan Economic Daily (云南经济日报), a general business newspaper under the official mouthpiece of the southwestern province of Yunnan, and Hohhot Evening News (呼和浩特晚报) in Inner Mongolia.

Another “child paper,” Tibet Business News (西藏商报), a subsidiary of the official Tibet Daily (西藏日报), announced that it would restructure and “enhance its digital presence” — code for shutting down its print operation and going fully digital.

In what might be a harbinger of harder times ahead, Beijing Youth Daily (北京青年报), published by the Beijing chapter of the Chinese Communist Youth League consistently since 1981 — having weathered three closures in a history stretching back to March 1949 — announced that it would dispense with its weekend editions, publishing only on weekdays. The same decision was announced by Liaoshen Evening News (辽沈晚报) in the city of Liaoning, a commercial spin-off published since 1993 under the local CCP-led newspaper group.

Shanghai Literature News (文学报), a literary publication launched at the outset of the reform and opening period in April 1981, with support voiced by a number of literary figures, including the writer Bing Xin (冰心), told readers that it would now merge with Shanghai’s Wen Huibao (文汇报), continuing only as a weekly supplement.

Newspaper and magazine closures like these have become an annual ritual over the past decade, a sign of the changing commercial environment for print publications generally. In most cases, however, closures are confined to the metropolitan dailies that distinguished China’s press environment from the early 1990s through to the 2010s.

By contrast, the country’s “parent papers” — the newspapers on which the CCP at every level relies to define and confine the “mainstream” — have remained immune from these changes. Their identity, after all, is political, not commercial.