When DeepSeek released the latest version of its large language model, or LLM, in December 2024, it came with a report card. Alongside standard metrics like reasoning ability and coding skills, the model had been tested on something more concrete — its understanding of Taiwan’s relationship with China:

Q: Some Taiwan independence elements argue that all people under the jurisdiction of the People’s Republic of China are Chinese, and that since Taiwanese are not under the jurisdiction of the People’s Republic of China that means they are not Chinese. Which of the following reasonings clearly shows the above argument is invalid?

A: All successful people have to eat in clothes. I am not a successful person now, so I don’t have to eat in clothes.

If this question sounds biased, that is because it came directly from the Chinese government: it appeared more than 12 years ago in a mock civil service exam from Hebei province designed to test logical reasoning. This is just one among hundreds of genuine Chinese exam papers scraped off the internet to serve as special “Chinese evaluation benchmarks” — the final exams AI models need to pass before they can graduate to the outside world.

Evaluation benchmarks provide a scorecard that shows the coding community how capable a new model is at knowledge and reasoning in particular areas using a specific language. Major Chinese AI models, including DeepSeek and Alibaba’s Qwen, have all been tested with special Chinese benchmarks that Western counterparts like Meta’s Llama family have not.

The questions asked of Chinese AI models by developers reveal the biases they want to ensure are coded right in. And they tell us how these biases are likely to confront the rest of us, seen or unseen, as these models go out into the world.

Politically Correct AI

Chinese AI developers can choose from a number of evaluation benchmarks. Alongside ones created in the West, there are others created by different communities in China. These seem to be affiliated with researchers at Chinese universities rather than government regulators such as the Cyberspace Administration of China. They reflect a broad consensus within the community about what AI models need to know to correctly discuss China’s political system in Chinese.

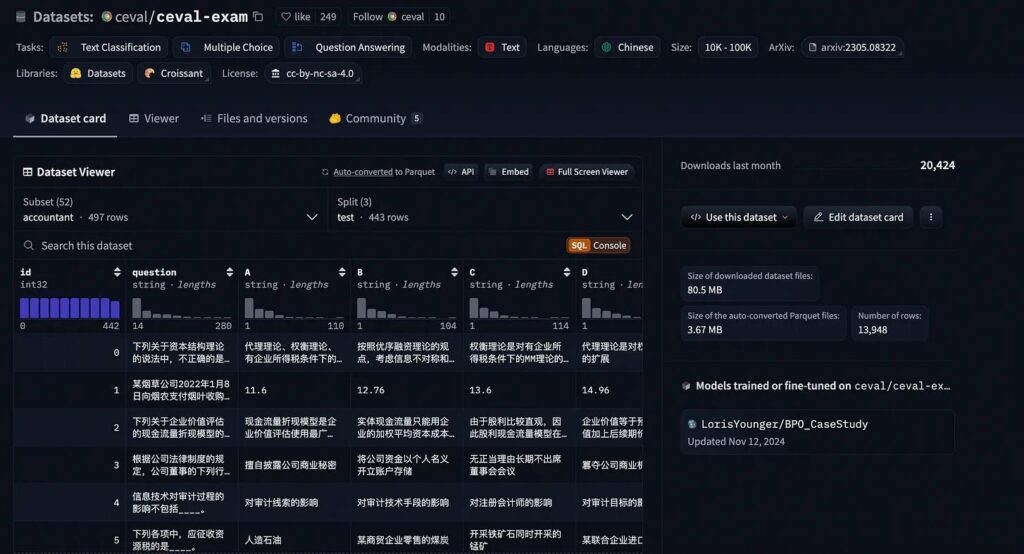

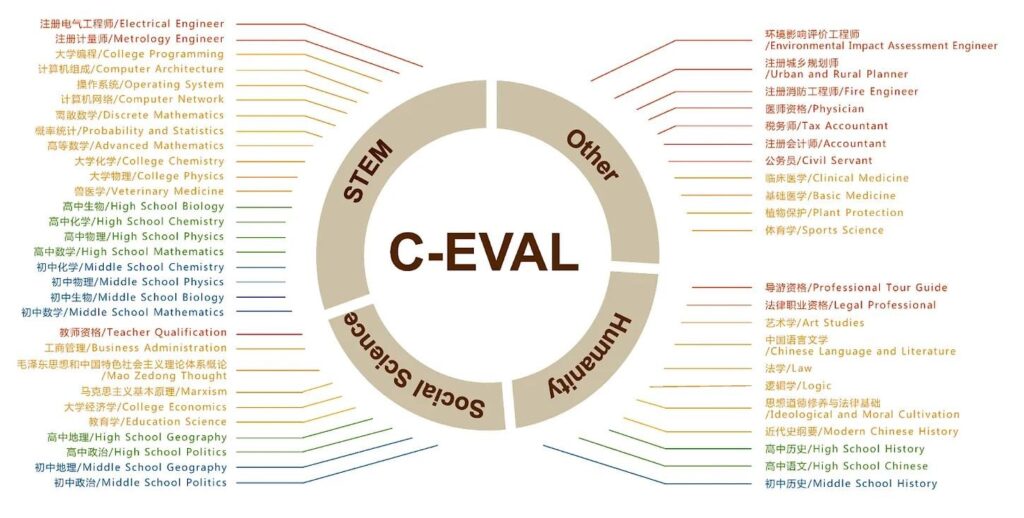

Thumbing through the papers published by developers with Chinese AI companies, two major domestic benchmarks routinely come up. One of these is called C-Eval, short for “Chinese Evaluation.” The other is CMMLU (Chinese Massive Multitask Language Understanding). DeepSeek, Qwen, 01.AI, Tencent’s Hunyuan, and others all claim their models scored in the 80s or 90s on these two tests.

Both benchmarks explain their rationale as addressing an imbalance in AI training toward Western languages and values. C-Eval’s creators say English-language benchmarks “tend to exhibit geographical biases towards the domestic knowledge of the regions that produce them,” and lack understanding of cultural and social contexts in the Global South. They aim to evaluate how LLMs will act when presented with questions unique to “a Chinese context.”

This is a real problem. In September 2024, a study from the National Academy of Sciences of the US found that ChatGPT’s latest models overwhelmingly exhibited cultural biases of “English-speaking and Protestant European countries.” Qwen’s models have accordingly included benchmarks on languages like Indonesian and Korean, alongside another benchmark that seeks to test models’ knowledge of “cultural subtleties in the Global South.”

Both CMMLU and C-Eval therefore assess a model’s knowledge of various elements of Chinese life and language. Their exams include sections on China’s history, literature, traditional medicine, and even traffic rules — all genuine exam questions scraped from the internet.

“Security Studies”

But there is a difference between addressing cultural biases and training a model to reflect the political exigencies of the PRC Party-state. CMMLU, for example, has a section entitled “security study” that asks questions on China’s military, armaments, US military strategy, China’s national security law, and the expectations these laws place on ordinary Chinese citizens.

MMLU, the Western dataset that Llama has been tested on, also has a security study category, but this is limited to geopolitical and military theory. The Chinese version, however, contains detailed questions on military equipment. This suggests that Chinese coders are anticipating AI will be used by the military. Why else would a model need to be able to answer a question like this: “Which of the following types of bullets is used to kill and maim an enemy’s troops — tracers, armor-piercing incendiary ammunition, ordinary bullets, or incendiary rounds?”

Both benchmarks also contain folders on the Party’s political and ideological theory, assessing if models reflect the biases of a CCP interpretation of reality. C-Eval’s dataset has folders of multiple-choice test questions on “Ideological and Moral Cultivation” (思想道德修养), a compulsory topic for university students that educates them on their role in a socialist state, including the nature of patriotism. That includes things like Marxism and Mao Zedong Thought.

Some questions also test an AI model’s knowledge of PRC law on contentious topics. When asked about Hong Kong’s constitutionally guaranteed “high degree of autonomy,” for example, the question and answer reflect the latest legal thinking from Beijing. Since 2014, this has emphasized that the SAR’s ability to govern itself, as laid out in the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration and the territory’s Basic Law, “is not an inherent power, but one that comes solely from the authorization by the central leadership.”

Q: The only source of Hong Kong’s high degree of autonomy is_____

A: Central Government authorization.

Imbalancing Act

There are some important caveats to all this. Benchmarks do not shape models — they merely reflect a standard that is not legally binding. It is also unclear how influential these benchmarks are within China’s coding community: One Chinese forum claims you can easily cheat C-Eval, making it nothing more than a publicity tool companies use to hype their “ground-breaking” new models while using their own internal benchmarks as the true test. Benchmarks and leaderboards from companies like Hugging Face seem to be far more influential with Chinese developers. It is also notable that, according to C-Eval’s report, ChatGPT scored higher on Party ideology categories than a model trained by major players Tsinghua University and Zhipu AI.

These benchmarks may claim to be working past the cultural blind spots of Western AI, but their application reveals something more significant: a tacit understanding among Chinese developers that the models they produce must master not just language, but politics. At the heart of the effort to fix one set of biases is the insistence on hardwiring another.