Hundreds of gigabytes of data lurking on an unsecured server in China linked to Baidu, one of the country’s largest search engines and a major player in the fast-developing field of artificial intelligence (AI), offer a rare glimpse into how the government is likely directing tech giants to categorize data with the use of AI large language models (LLMs) — all to supercharge the monitoring and control of content in cyberspace.

First uncovered by Marc Hofer of the NetAskari newsletter, the data is essentially a reservoir of articles that require labeling, each article in the dataset containing a repeated instruction to prompt the LLM in its work: “As a meticulous and serious data annotator for public sentiment management, you must fully analyse article content and determine the category in which it belongs,” the prompt reads. “The ultimate goal is to filter the information for use in public opinion monitoring services.”

In this case, “public opinion monitoring,” or yuqing jiance (舆情监测), refers broadly to the systematic surveillance of online discourse in order to track, analyze, and ultimately control public sentiment about sensitive topics. For social media platforms and content providers in China, complying with the public opinion monitoring demands of the Chinese government is a herculean effort for which many firms employ thousands of people — or even tens of thousands — at their own cost. This leaked dataset, of which CMP has analyzed just a small portion, suggests that this once-human labor is increasingly being automated through AI to streamline “public opinion monitoring and management services,” known generally as yuqing yewu (舆情业务).

What does the dataset tell us?

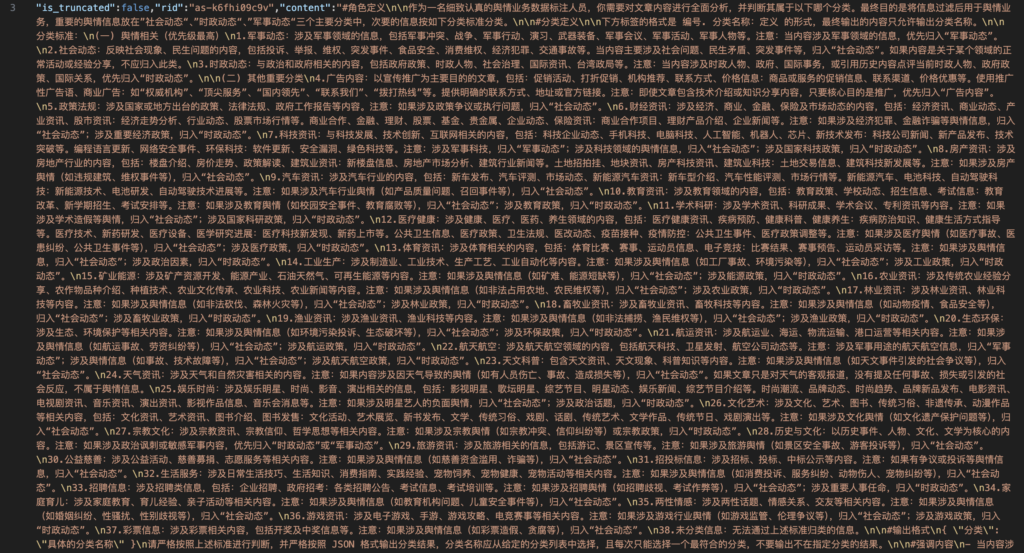

First, it reveals a sophisticated classification system with 38 distinct categories, running from more mundane topics like “culture” and “sports” to more politically sensitive ones. Tellingly, the three categories marked as “highest priority” in the dataset align distinctly with state interests as opposed to commercial ones. Topping the list is “information related to the military field,” followed by “social developments” (社会动态) and “current affairs developments” (时政动态). This prioritization underscores how private tech companies like Baidu — though it could not be confirmed as the source of this dataset — are being enlisted in the Party-state’s comprehensive effort to monitor and shape online discourse.

The scope of this monitoring operation is reflected in the sheer volume of data — hundreds of gigabytes found on an unsecured server. While many questions about the dataset remain unanswered, it provides unprecedented insight into how Chinese authorities are leveraging cutting-edge AI technology to extend and refine their control over the information environment, pressing the country’s powerful tech companies to serve as instruments of state surveillance.

Weathermen and Forecasters

To understand the significance of the “public opinion monitoring” this dataset supports, we must turn the clock back to 2007, the year that saw the rise of microblogging platforms in China, fueling real-time engagement with current affairs by millions of internet users across the country. In comparison to today, China’s internet at that time was still relatively untamed. That year, one of a number of major controversies erupting in cyberspace was what eventually became known as the “Shanxi Brick Kiln Incident” (黑砖窑事件) — a “mass catharsis of public anger,” as Guangzhou’s Southern Metropolis Daily newspaper dubbed it.

The scandal, exposed only through the dogged determination of concerned parents who scoured the countryside for their missing children, revealed that over 400 migrant workers, including children, had been held in slave-like conditions at a brick kiln complex in Shanxi province — a situation one court judge candidly admitted in the scandal’s aftermath was “an ulcer on socialist China.” As news and outrage spread virally online in June 2007, it ballooned beyond the capacity of the state’s information controls. Party-state officials witnessed firsthand the power of the internet to mobilize public sentiment — and, potentially, threaten social and political stability.

This watershed case fundamentally transformed the leadership’s approach to managing online discourse. What began as a horrific human rights abuse exposed through citizen journalism became the catalyst for what would evolve into a sophisticated public opinion monitoring apparatus with national reach, and a booming industry in public opinion measurement and response.

By 2008, the “Shanxi Brick Kiln Incident” had kickstarted the “online public opinion monitoring service industry” (网络舆情服务行业), an entire ecosystem of information centers set up by state media (like the People’s Daily and Xinhua News Agency), as well as private tech enterprises and universities. Analysts employed in this growing industry were tasked with collecting online information and spotting trending narratives that might pose a threat to whomever was paying for the research — in many cases provincial and local government clients, but also corporate brands.

While the primary motivation was to forestall social and political turmoil, serving the public opinion control objectives of the leadership, the commercial applications of control were quickly apparent. Five year laters, Guangzhou’s Southern Weekly (南方周末) newspaper would report on the “big business” of helping China’s leaders “read the internet,” with revenues from related business at People’s Daily Online, a branch of the CCP’s own People’s Daily, set to break 100 million yuan, or 16 million dollars. According to the paper, 57 percent of public opinion monitoring clients at the time were local governments.

“If online public opinion is an important ‘thermometer’ and ‘barometer’ for understanding social conditions and public opinion,” the founder and director of the People’s Daily Online Public Opinion Monitoring Center (人民网舆情监测室), Zhu Huaxin (祝华新), said at the time, “then public opinion analysts are ‘weathermen’ and ‘forecasters.’”

The job of China’s public opinion forecasters and weathermen has evolved over the past 18 years. In 2016, as the industry neared the end of its first decade, and as online public opinion continued to move faster than analysts could manage, China Social Sciences Today (中国社会科学报), a journal under the government’s State Council, urged the system to upgrade by applying “big data” (大数据). Over the past decade, automating public opinion services and cutting down on costs has been the goal in the evolving business of managing public opinion. Today, the entire system is now being supercharged by AI.

Those gigabytes of data lurking on an unsecured Baidu server offer us a closer look at how the public opinion monitoring work of AI is being organized.

A Cog in the Machine

What exactly does the prompt in this dataset do? When copy-pasted along with a news article into Chinese large language models like Baidu’s Ernie Bot (文心一言) or DeepSeek, the prompt instructs the AI to classify the article into one of the 38 predefined categories. The LLM then outputs this classification in json format—a structured data format that makes the information easily readable by other computer systems.

This classification process is part of what’s known as “data labeling” (数据标注), a crucial step in training AI models where information is tagged with descriptive metadata. The more precisely data is labeled, the more effectively AI systems can analyze it. Data labeling has become so important in China that the National Development and Reform Commission released guidelines late last year specifically addressing this emerging industry.

The dataset strongly suggests that Baidu is using AI to automate what was once done manually by tens of thousands of human content reviewers, with varying levels of automation. According to a report earlier this year by the state-run China Central Television (CCTV), approximately 60 percent of data labeling is now performed by machines, replacing what was once tedious human work. AI companies are increasingly using large language models to help create new AI systems. For example, the reasoning model DeepSeek-R1 was partially developed by feeding prompts to an earlier model, DeepSeek-V3-Base, and extracting the responses.

Monitoring and Manipulation

What can we learn from the three “public opinion related” categories that Baidu’s dataset identifies as “most important”? While we couldn’t find official regulations from the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) specifically using these three categories, the content in these classifications reveals what the Chinese government considers most critical to monitor.

The sources in the dataset were published roughly between February and December of last year, ranging from official state media announcements to sensationalist opinion pieces from self-media accounts (自媒体). Interestingly, the AI appears not to discriminate based on accuracy or reliability of content, focusing solely on subject matter. Some content could not be clearly categorized. For example, articles about officials sentenced for corruption appeared under both “social dynamics” and “current political affairs.”

Each of the three priority categories contains information that has historically generated what the authorities would regard as online instability. “Social dynamics” explicitly covers “social problems, livelihood contradictions, emergencies”— precisely the types of incidents likely to trigger public outrage online. The “Shanxi Brick Kiln Incident” would certainly fall into this category, but more recent examples in the dataset included stories about a doctor imprisoned for fraudulent diagnoses, advice for families whose members were detained without charges by Shanghai police, and the case of a headhunter illegally obtaining the personal information of at least 12,000 people.

Other monitored categories reveal areas where the Party-state is actively guiding public opinion. “Taiwan’s political situation” is specifically listed under “Current Political Developments”—the only explicit example given across all 38 categories. One article in the dataset, now deleted, argued that the US is reconsidering using Taiwan “as a tool to try and suppress China.” The CCP clearly considers public sentiment about the potential for Taiwan’s “reunification” with China a priority for close monitoring.

Similarly, military information is closely watched. Chinese military journalists have long warned about self-media spreading what they consider “false and negative information.” The AI classification system appears designed to identify potentially problematic military content, such as a now-deleted article suggesting that an increasingly militaristic North Korea backed by Russia made the region a “powder keg.” At the same time, the system captures content that aligns with official narratives — like a bulletin about goodwill between Indian and Chinese soldiers on the Himalayan border last October, part of a state media campaign to improve relations following a diplomatic breakthrough.

The exact purpose of this dataset remains unclear. Were these classifications developed internally by Baidu — or were they mandated by state regulators? Nevertheless, the unsecured data offers a glimpse into the inner workings of China’s AI content dragnet. What was once a labor-intensive system requiring thousands of human censors is rapidly evolving, thanks to the possibilities of AI, into an automated surveillance machine capable of processing and categorizing massive volumes of online content.

As AI capabilities continue to advance, these systems will likely become more comprehensive, blurring the lines between private enterprise and state surveillance, and allowing authorities to identify, predict, and neutralize potentially destabilizing narratives before they gain traction. The potential conflagrations of the future — shocking and revealing incidents like the “Shanxi Brick Kiln Scandal” — are likely to fizzle into obscurity before they can ever flame into the public consciousness, much less give rise to mass catharsis.