With 12 million fresh graduates soon rushing into China’s already competitive job market, help is on the way, according to the People’s Daily. On April 7, the newspaper, the official mouthpiece of the country’s leadership, ran an article listing how AI was turbo-charging supply and demand in the job market, pointing to over 10,000 AI-related jobs on offer at a spring recruitment center in the city of Hangzhou. The piece was accompanied by a graphic from Xinhua, showing a smiling recruiter handing out jobs (岗位) to incoming students, with an AI bot ready and waiting to embrace them with open arms. The message is clear: graduates can literally walk into AI-related positions.

But according to the Qianjiang Evening News (钱江晚报), a commercial metro newspaper published in Hangzhou under the state-owned Zhejiang Daily Newspaper Group, the reality is a lot tougher for new graduates. “It’s hard to find a job with a bachelor’s degree in this major,” said one of their interviewees, a recent graduate majoring in AI who was quoted under the pseudonym “Zhang Zixuan.” The graduate said they had gone to multiple job fairs without securinig a job. “I don’t know the way forward,” they told the paper.

China’s biggest tech companies are indeed angling for the leading edge in AI, battling it out to hire “young geniuses” (天才少年) graduating from AI programs at China’s top universities. But while these rarefied talents — whoever they are — may have their choice of elite positions, the picture is less rosy for the vast majority. “Despite the booming industry,” Qianjiang Evening News concludes, “many recent graduates of artificial intelligence majors from ordinary universities are still struggling in the job market.”

Hangzhou is now billed by Chinese media as a major hub for AI innovation and enterprise, home to China’s foremost large language model (LLM), DeepSeek. But if the city’s media are saying there are significant problems with AI recruitment, the rest of the country is likely experiencing similar complications. State-run media and universities in China are presenting the government’s AI policies as a gift for the nation’s entry-level job market. But these messages paper over a more complex reality.

The Hunt for AI Talent

The government has made it a priority to boost national AI development. In the government work report last year at the Two Sessions, China’s major legislative meeting, Premier Li Qiang launched the “AI+” initiative (人工智能+行动). The initiative aims to augment AI for every industry in the country, considering it a way to unlock “new productive forces” (新质生产力) — a signature phrase of Chinese leader Xi Jinping — that will bolster China’s economy and job market.

The latter needs it. Youth unemployment in China stands at 16.9 percent as of February this year, and comes at a time when graduate supply has never been higher. There are nearly four million extra graduates in the class of 2025 than there were even five years ago.

The stiff competition for jobs is a source of frustration for young Chinese. Earlier this month, Guangzhou’s Southern Metropolis Daily (南方都市报) reported that the state-owned nuclear power company CNNC had publicly apologized after boasting online that it had received 1.2 million resumes to fill roughly 8,000 positions. The company was accused by netizens of “arrogance.”

Aligning university education to accommodate AI training is considered by the leadership as key to harnessing this technology of the future. In 2017, a document from the State Council noted the country lacked the “high-level AI talents” needed to make China a global leader in AI technology. In 2023, the Ministry of Education issued a reform plan ordering that by this year 20 percent of university courses must be adjusted, with an emphasis on emerging technologies and a gradual elimination of courses “not suited for social and economic development.”

Universities across the country have responded with dramatic overhauls of their curricula. Ta Kung Pao (大公报), the Party’s mouthpiece in Hong Kong, reports universities in neighboring Guangdong province have already established 27 AI colleges, which are supposedly training 20,000 students a year. Meanwhile, universities like Shanghai’s Fudan University announced they will be cutting places in their humanities courses by 20 per cent as ordered, focusing instead on AI training. For Jin Li (金力), Fudan’s president, university courses must now explicitly serve China’s state-directed technological development goals. “How many liberal arts undergraduates will be needed in the current era?” he questioned rhetorically.

Technical Problems

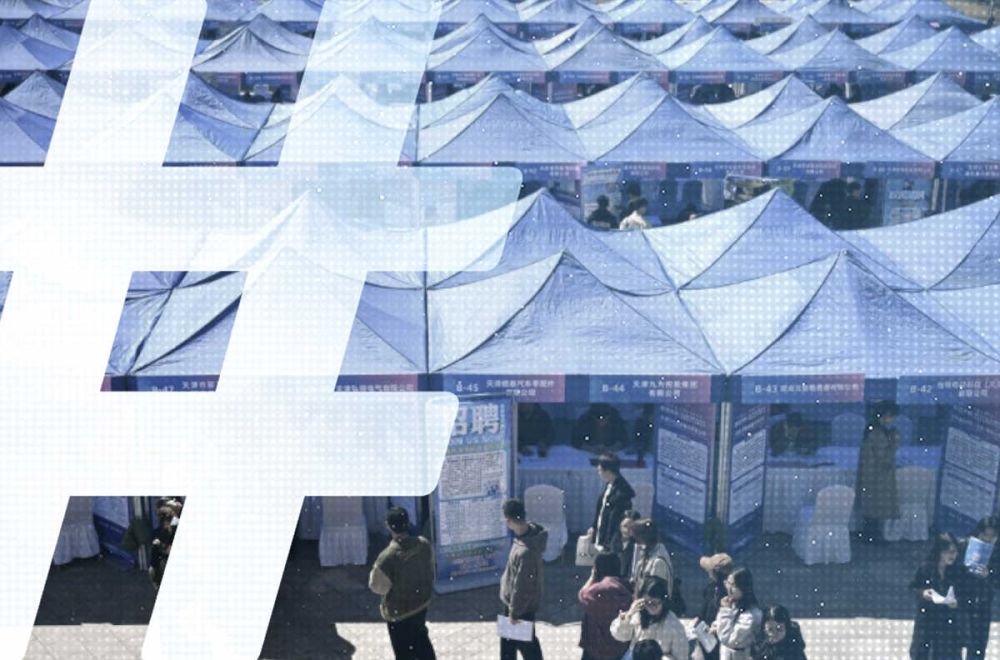

State media says AI+ is already successfully reinvigorating the job market. Attending one job fair in Beijing this month, a reporter for the China Times (华夏时报), a media outlet under the State Council, noted a “surge in demand” among state-owned enterprises (SOEs) for AI talent, quoting one graduate trained in AI as saying he had seen “many work units that meet my job expectations.” Visiting job fairs in Shanghai and Guangdong, a reporter for Shanghai Securities News (上海证券报), a subsidiary of state news agency Xinhua, observed long queues in front of booths for jobs on algorithm engineering and data labeling. On that basis, he wrote “AI fever” had gripped the gatherings.

AI itself is also spreading positive messages about the jobs it can bring. Ahead of the Two Sessions this year, People’s Daily Online (人民网) pitched DeepSeek as helping citizens understand the “happiness code” (幸福密码) embedded in the Two Sessions. It does this by describing state-imposed solutions to current social problems, to ease the concerns of netizens.

One question the outlet asked was on what AI jobs were available to recent graduates. When we at the China Media Project asked DeepSeek the same question, it told us AI “offers abundant employment opportunities for recent graduates,” listing several well-salaried ones. One of these was “data labeling” (数据标注) with DeepSeek saying these positions are increasing by 50 percent year-on-year. The source for this claim was an article from the Worker’s Daily (工人日报), a newspaper under the CCP-led All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), the country’s official trade union.

It should go without saying that the role of the ACFTU’s newspaper is to promote the leadership’s economic agenda rather than to accurately report the challenges for the nation’s workforce posed by technological change. This role can mean, once again, that hype takes precedence over fact. In this case, the Worker’s Daily cited the case of a data-annotation college in Shenzhen, suggesting that graduates from the college receive 10 job offers on average within an hour of uploading their resumes online.

Even if such data annotation roles are available right now, this does not point the way to a rosy future for aspiring young data annotators more broadly. Some data annotation roles, in fact, require few qualifications, and fresh trainees may be trusted by tech companies to do this work after just three weeks of training. Relatively unskilled jobs like this may be created by AI, but they are also vulnerable to replacement by AI itself. China’s state broadcaster CCTV reports that 60 percent of data annotation is now being done by AI, doubling in just three years.

The CCTV report points to a trend that few state media seem to be openly acknowledging amid the hype over AI jobs — that the field is already shifting towards more specialized employees. That will mean raising the bar for data annotator qualifications, and fewer people ultimately required to do this work. In its report, the Qianjiang Evening News quotes an anonymous application engineer as saying the number of data labellers at his company is decreasing already. “Big models can label themselves,” he told the newspaper.

The same report suggested that the demand for AI skills varies widely between companies. Zhang, the pseudonymous recent graduate, said that most of the companies at the university job fairs in which they participated did not have AI-related jobs on offer. The ones that did have such jobs demanded a higher degree of education, generally as the master’s level. The concerning lesson drawn from Zhang’s experience is that the training provided by these new AI education centers does not suit current demand from tech companies — to say nothing of future demand. While companies often require in-depth expertise within specialized areas like fine-tuning AI models, AI courses often sacrifice depth by giving their students shorter periods of training in a wide variety of AI skills.

Another concern emerges: who will teach the next generation of AI specialists? The sudden expansion of colleges to accommodate the needs of the AI+ initiative is no doubt creating a talent dearth of its own. In a speech earlier this month, a senior scientist from Peking University claimed many AI centers employed inexperienced professors in order to fill teaching positions. He added that certain AI centers were moving members of their mathematics and art colleges to serve as “part-time” deans of these centers.

Vocational schools could struggle even more. These colleges are usually stigmatized in Chinese society, stereotyped as only attended by students who failed their university entrance exams. This would put them at the bottom of the pile for aspirational AI talent. For example, one vocational college in Hubei says it created an AI major in response to the Ministry of Education’s push to cultivate high-quality AI talent. But it is advertising AI teaching positions where prior experience in this complex field is merely “preferred” rather than required.

It should come as no surprise that state media narratives of jam-packed job fairs handing out AI positions are overly optimistic. The disconnect is stark. While the handful of elite graduates at the pinnacle of China’s AI sector may enjoy rich opportunities, it is misleading to suggest that their exceptional success stories are evidence that AI has promised employment for the broader masses. The larger context matters: as Xi Jinping’s government pushes AI as a cornerstone of China’s economic future, a widening gap has formed between top-down ambitions and on-the-ground realities for millions of graduates. Instead of excitedly focusing on the long queues at AI stalls in job fairs, Chinese media should also be asking deeper questions about the issues that create them.