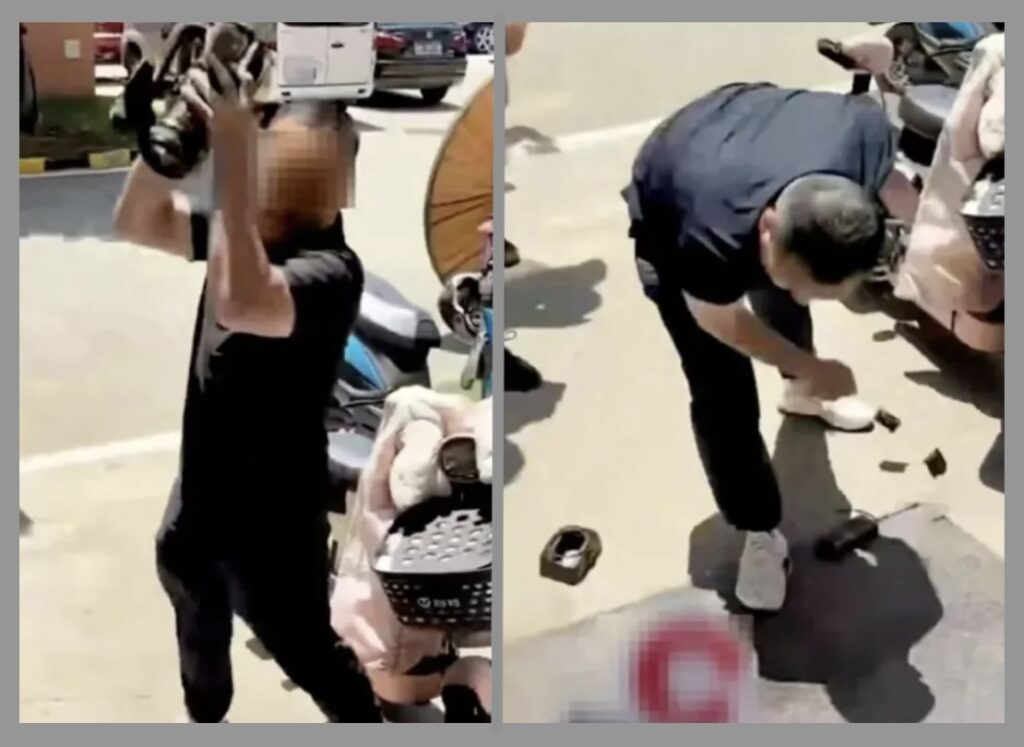

On July 15, journalists investigating consumer reports of substandard electrical cable products at an industrial park complex in the southern Chinese province of Hunan were attacked by the executive of a cable company during a reporting visit to the firm’s offices. In an altercation that was caught on video and took social media by storm, the man was shown smashing a reporter’s filming equipment to pieces.

As the story turned on the perpetrator of the violent act, a 42-year old boss at Hunan Fengxu Cable Company (湖南豐旭線纜有限公司) identified only as Mr. Xie, the All-China Journalists Association (ACJA) — an ostensible professional association for the media that more fully represents the interests of the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) — spoke out in support of the reporters. In a sanctimonious missive, the association declared that “interviewing is a journalist’s right” (采访是记者的权利).

It was a welcome idea, certainly. But it was also deeply hypocritical coming from a Party-run association the puts politics and news control at the forefront of its work, perpetuating and defending Xi Jinping’s vision of the press as a tool for the Party’s interest and for “positive propaganda.”

Since Xi’s press policy took full shape in February 2016, it has revolved around the notion of the “Four Firm Adherences” (四个牢牢坚持), which uphold 1) the CCP nature of the media (essentially, serving the Party); 2) the Marxist View of Journalism (which again puts the Party at the center); 3) “correct guidance of public opinion,” a buzzword for media control to maintain social and political stability dating back to the political turmoil of 1989; and 4) “emphasizing positive propaganda” (正面宣传为主), the principle that media should generally avoid critical reporting in favor of the uplifting and constructive.

Needless to say, these four interlocking concepts — which the ACJA has dutifully upheld — are a recipe for compliance and lack of agency. To the extent that Chinese media have turned their CCP-given powers to playing a monitoring role, this has happened through what is generally known as “supervision by public opinion” (舆论监督), a concept unique to China’s highly controlled press environment. This form of supervision generally entails press reporting of small-time abuses that do not touch directly on the interests of the Party-state. And more recently, in a further reigning in of journalists in which the ACJA has played an active role, Xi Jinping has emphasized the unity of “supervision” and “positive propaganda” — meaning that coverage should direct through positivity and praise, rather than correct.

It was around this much mythologized notion of supervision that the ACJA and state media shaped their outrage over the destruction of the reporter’s filming equipment in Hunan. In its high-minded statement, the association affirmed that “legitimate supervision by public opinion is protected by law” (正当舆论监督受法律保护). Who gets to decide what types of probing coverage are “legitimate”? The answer, again, is the Party, as the “Four Firm Adherences” make clear.

Despite his emphasis on anti-corruption, Xi Jinping has severely constrained the already limited supervisory role of China’s press, viewing the war against corruption as a matter of internal CCP “discipline” rather than outside supervision.

In fact, despite his reputation for centralizing and consolidating political control, Xi has actually empowered leadership at every level of China’s vast bureaucracy to determine news coverage and its constraints. Local authorities now exercise more control over media than at any previous point in the reform era. News feeds at major online outlets like Shanghai’s The Paper (澎湃) are filled with news and promotional releases from government-run social accounts, a vast web of self-promotion. Crime and legal news? Don’t look to your local journalism team. The story has been covered by a ”police incident report” (警情通报) directly from a district or city police precinct.

Swatting at Flies

Against this backdrop of strict press control and local information empowerment, the ACJA’s talk of journalist’s rights does not accord with political realities. The true right to report is vested in those who wield political power, which is why only protected state media outlets can pursue “supervision” in China today against small-time consumer concerns, or malfeasance by small companies and individuals. This is sometimes referred to critically in Chinese as “swatting flies and letting tigers run free.”

Even these state media journalists are not safe from harassment when reporting local stories. In one recent case in March 2024, a filming crew from the Party-run China Media Group (CMG), reporting for the state broadcaster China Central Television (CCTV), was hustled away from the scene of a deadly gas explosion in Henan province during a live broadcast. How could that happen? Because the real media policy at the state-level, and therefore at every level beneath, is information suppression. What really unfolded on live television last year was not about journalists exposing the truth to the public. Rather, it was about who would exercise what level of control over the story. It goes without saying that CMG and CCTV, which are directly under the Central Propaganda Department, have their own “discipline” to enforce.

Nevertheless, as the ACJA spoke up over the Hunan incident this month, CCTV was quick to amplify the language about journalists’ rights. Provincial-level state outlets followed suit. Jilin province’s state-run news site declared in a commentary that it was nonplussed by the events at the industrial park complex in Hunan. “It is hard to believe that such violations of journalists’ legitimate rights could occur in broad daylight in a society governed by law,” it wrote.

In what might be regarded as a blatant violation of Party orthodoxy outside this moment of state media outrage, the Jilin commentary ventured even to say that legal protections for journalists are necessary because “only then can the news media properly serve as the sentries of society.” We should remember that the CCP’s Document 9, released in 2013, explicitly attacks the notion of the press as “society’s public instrument.”

As a matter of policy, China’s media are most definitely not “sentries of society.” As the “Four Firm Adherences” make clear, they are to do the CCP’s bidding, and to defend its interests — even if that means crushing a story, pulverizing facts, or smashing cameras.

As shocking as the scene outside the Hunan Fengxu Cable Company might have been, nothing whatsoever about it is difficult to believe. China’s constitutional right to freedom of expression is routinely trampled by a system that pulls journalists back from breaking stories, directs them to avoid sensitivities, and obliterates online posts in the millions.

Mr. Xie is not a monstrous outlier. He is a raw and rough allegory for the system as it was designed.