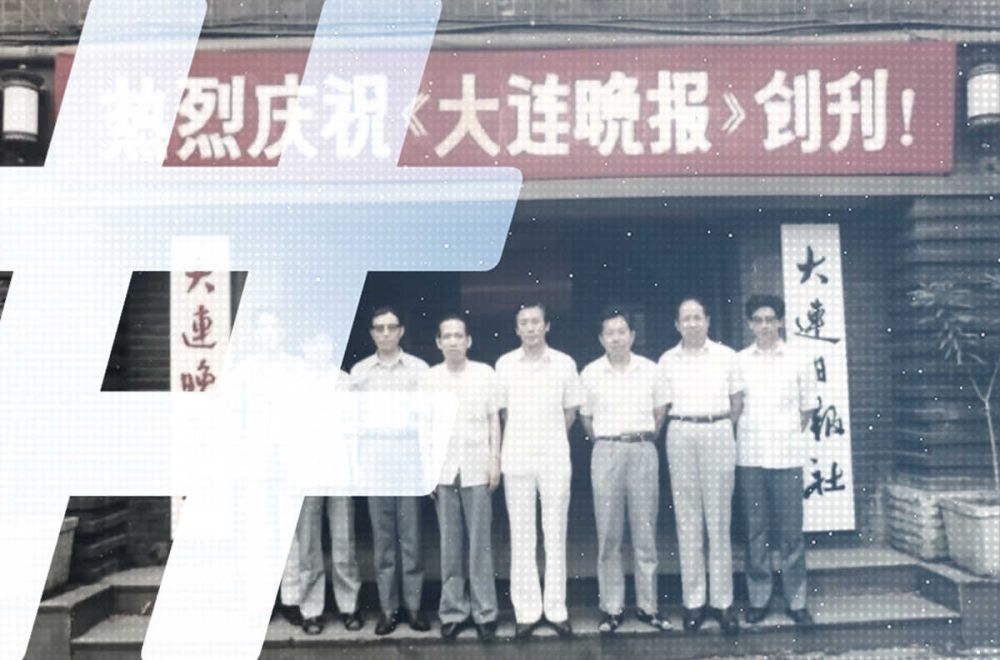

The Dalian Evening News, a fixture of daily life in the northeastern port city for 37 years, published its final edition on December 30, announcing it would cease publication with a brief notice thanking readers and contributors. The closure makes it the second major newspaper in Dalian to fold in recent years, following Xinshang News (新商报), which ceased publication in 2019.

Founded in 1988, the Dalian Evening News (大连晚报) was part of a wave of metropolitan newspapers that proliferated across China during the reform and opening era, serving as a key source of local news and advertising. These papers emerged in the early 1990s, with the metropolitan newspaper model accelerating after 1995 with the establishment of Chengdu’s Huaxi Metropolitan News (华西都市报) as the prototype for commercial urban dailies, followed by staples such as Guangdong’s Southern Metropolis Daily (南方都市报), founded in 1997. Through to the Xi Jinping era these and other commercial papers were at the heart of a slow-burning professional revolution for journalism in China, breaking important and socially, even politically, relevant stories. Huaxi Metropolitan News, for example, was instrumental in early reporting on the AIDS epidemic in Henan province caused by contaminated blood collection practices that infected as many as a million people.

The Dalian Evening News is one of approximately 14 newspapers that announced cessation or suspension around the start of 2026, including Jiangnan Travel News (江南游报) in the Yangtze River Delta, Yanzhao Rural News (燕赵农村报) in Hebei province, and Langfang Metropolitan News (廊坊都市报) in Langfang, Hebei.

Folding Up

At least 14 newspapers announced cessation or suspension at the start of 2026 in China, marking another wave in the ongoing decline of China’s print media sector.

| Newspaper Name | Chinese Name | Founded | Years Active |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dalian Evening News | 大连晚报 | 1988 | 37 years |

| Jiangnan Travel News | 江南游报 | 1986 | 38 years |

| Yanzhao Rural News | 燕赵农村报 | 1964 / 1982 (relaunched) | 60 years |

| Pingyuan Evening News | 平原晚报 | 2004 | 20 years |

| Langfang Metropolitan News | 廊坊都市报 | 2009 | 16 years |

| Huanghai Morning Post | 黄海晨刊 | 2003 | 22 years |

| Yandu Morning Post | 燕都晨报 | 2003 | 22 years |

| Suqian Evening News | 宿迁晚报 | 2001 | 24 years |

| Linchuan Evening News | 临川晚报 | 2017 (media convergence) | 8 years |

| Xinyu News | 新渝报 | 1926 | 99 years |

| China Philatelic News | 中国集邮报 | 1992 | 33 years |

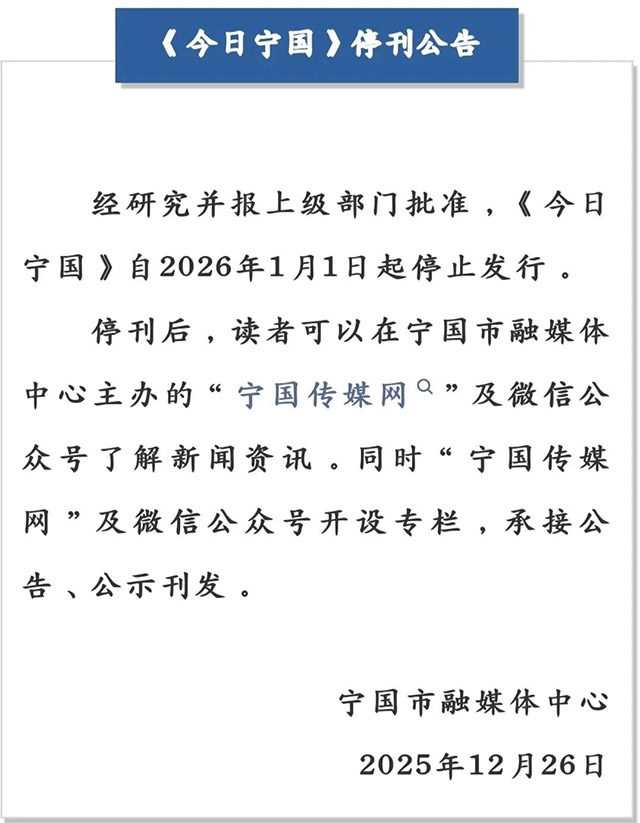

| Today Ningguo | 今日宁国 | Unknown | — |

| Yalu River Evening News | 鸭绿江晚报 | 1996 | 29 years |

| Southern Radio & TV News | 南方声屏报 | 1994 | 31 years |

The wave of closures reflects years of financial crisis in Chinese print media stemming from broader changes in the media landscape in China and globally. Newspaper advertising peaked in 2011, then declined 55 percent by 2015 — and the freefall continued. By 2021, newspaper advertising revenue had shrunk to just one-fifteenth of what it was in 2011. Metropolitan newspapers were hit hardest: commercial advertising dropped over 70 percent, with some papers reduced to operating with zero advertising and forced to rely on their parent organizations for survival.

Circulation has similarly collapsed. Subscription and newsstand sales in 70 major Chinese cities plunged 46.5 percent in 2015, with metropolitan newspapers declining 50.8 percent.

Peking University professor Zhang Yiwu (张颐武) explained in analysis two years ago that short videos and livestreaming have replaced text-based newspapers as readers’ information consumption habits have changed. The most profitable local media outlets — metropolitan newspapers and evening papers — took the hardest hit, he said. Party newspapers maintained operations because the government needed them to disseminate propaganda and other official information. Zhang described the decline as initially gradual, giving false hope for recovery, but then becoming cliff-like, with many newspapers ultimately destroyed by their own wishful thinking about a potential rebound.

The decline of commercial print newspapers and periodicals in China since around 2010 has had a dramatic impact on the professional journalism cultures that once flourished in these contexts. The more local and relevant reporting they once fostered has also suffered in the face of efforts under Xi Jinping to wrest back control of news reporting, in part by building up Party-run digital convergence media centers (融媒体中心) and empowering local government bodies to lead on digital communication. One sign of this latter trend has been the proliferation of “blue notices” (蓝底通报), official statements released by local authorities on social media that sideline professional journalists and replace independent reporting with government-controlled narratives.

In its year-end reflection, the WeChat public account Aquarius Era (水瓶纪元), run by veterans of China’s commercial newspaper era, described its mission as telling “stories outside the blue background and white text” (蓝底白字之外的故事), a clear criticism of the dominance of official blue notices and the news vacuum in which they dominate. The year-end letter affirmed that despite intense censorship, journalists from different generations continue work in their own ways to document overlooked people and events.

The decline of print media can be seen in the precipitous decline of newsprint consumption, which has devastated the paper industry over the past decade. The Chinese newspaper industry reached its peak in 2012 with domestic newsprint production of 385 million tons annually and over 20 paper mills operating, but declining demand has forced most mills to reduce production or shut down entirely. According to the China Newspaper Association (中国报业协会), nationwide newspaper newsprint consumption totaled just 106.4 million tons in 2023, projected to decline another 3 percent to approximately 103.2 million tons in 2024, leaving only three newsprint producers nationally.

Rather than outright closures — though that is the real meaning — many newspapers are now choosing to announce “suspension” over permanent closure. The reason for that is political and regulatory, rather than commercial or financial. Under China’s tightly controlled press system, all news and other publishing or media outlets that do original content production are required to have licenses, or kanhao (刊号), scarce administrative resources issued by the National Press and Publication Administration that cannot be easily reacquired. By announcing suspension rather than closure, newspapers preserve these licenses even as they cease operations indefinitely.

Because in an era of profound digital, economic and political uncertainty, you just never know.