By David Bandurski — In an article earlier this week, Nick Young explained the circumstances surrounding the shutdown this summer of his non-profit journal, the China Development Brief. Based on Chinese journalist Zhai Minglei‘s (翟明磊) account of the closure of the civil society journal Minjian, both publications seem to have been the victims of a concerted campaign by government authorities against publications servicing the NGO sector in China.

The decisions to shut down the China Development Brief and Minjian were not made in consideration of China’s laws, but administrative regulations offered the pretext when those in power — fearful, says Young, of “color revolutions” elsewhere in the world — felt it was time to move against them. Alluding to periodic law-enforcement crackdowns, Zhai has suggested the recent moves are part of an “intellectual strike hard campaign.”

Both journals had taken advantage of a degree of apparent tolerance in China’s publishing sector that allowed them to operate without official publishing licenses, or kanhao (刊号).

Young and Zhai Minglei cite similar reasons for deciding to publish in the way they did:

YOUNG: “Neither [our English or our Chinese] newsletter complied with China’s highly restrictive publishing laws, which entail political controls that prevent the kind of objective and independent reporting that we offered. But we seemed to have found a lacuna of tolerance that, I believed, might presage the gradual advance of free expression.”

ZHAI: “One reason Minjian did not have a publishing license is because under China’s current publishing environment, publishing licenses are held and controlled by publishing organs designated by the state . . . As a resource for the public good promoting action on public welfare, Minjian had no aims to profit in the marketplace, nor did we want to bear this unjust cost. Even more important was the sponsoring institution and press censorship that would come with the publishing license. [Note_Bandurski: In China all licenses for publishing are held by sponsoring institutions, or zhuguan danwei (主管单位), that are responsible for ensuring party propaganda discipline at publications under their watch.] Minjian had no intention of tying its own hands and feet.”

Zhai and Young were not alone. Literally thousands of magazines and newsletters, academic and otherwise, continue to publish in China without licenses. And as Zhai points out, if the authorities were to uniformly apply their logic in going after Minjian and the China Development Brief , then . . .

“all of the internal organizational publications and materials of NGOs in China are illegal publications . . . [a]nd so it is with all of those small booklets we circulate among friends and acquaintances in China as a form of interaction or to seek the appreciation of friends, or those various poetry collections we call people’s publications (民刊), all reading materials shared among colleagues. All they need is to be printed and they are illegal publications.”

The experiences of Zhai and Young suggest publications in this grey area may be living on borrowed time as Chinese leaders grow ever more wary of China’s nascent civil society, particularly amidst growing civil unrest.

As Young put it: “The tolerance evaporated this summer.”

In many cases, the accusations leveled against the editors by state police cross the border into the bizarre, suggesting Chinese leaders are growing increasingly paranoid about social and political unrest and the role information might have in organizing resistance.

Both Young and Zhai attempt to reassure authorities that their actions are not politically motivated, that they are not “enemies” taking part in conspiracies against those in power. Nevertheless, Zhai is accused at one point, utterly without basis, of helping form a “reactionary organization” with U.S. backing:

Last year the Center for Civil Society held a workshop and posted a pre-announcement online. After the announcement appeared, the abovementioned Web authorities maintained that a reactionary organization called “Workshop” had recently been formed, supported by Americans. Only after a lot of explaining from a number of sides did the authorities admit they had been seriously misinformed by this grave notice of enemy threats.

Likewise, when facing his mysterious interlocutor, Mr. Song, Young gets a glimpse of the brutal, manichean logic of Chinese security officials, for whom there are only enemies and friends. “You can be the government of China’s friend or our enemy; there is no other way,” he is told.

In an interesting parallel with Zhai’s case, Mr. Song tells Young police have “evidence” that the China Development Brief was linked to Xinjiang freedom fighters:

He began by saying he had evidence of our links with Xinjiang separatist organizations. This opening gambit shows both how closely we had been monitored and how sensitive an issue Xinjiang is for Beijing. The “evidence” almost certainly referred to an e-mail exchange two years ago with a Uighur exile group. We contacted them while researching a report that, in the end, I did not publish because it had been too hard to find information that was both new and reliable.

In both cases, the editors fail ultimately to reason with authorities. In response to the suggestion of “links” with Uighur separatists, Young says to Mr. Song:

I told Song this [about an e-mail contact with a Uighur exile group], adding that I believe Beijing is courting disaster in Xinjiang by using heavy-handed treatment against its Muslim population. China, I argued, should learn from rather than mimic the calamitous failures of Western countries in their relations with the Islamic world.

Young’s only answer is his brutal choice: enemy or friend. When he attempts to re-enter China after a stay overseas, he is turned back and his visa nullified.

As a Chinese citizen, Zhai Minglei potentially faces more serious consequences for his actions –even if they do not violate Chinese laws — and that could include a prison term.

Nevertheless, Zhai too attempts to meet the authorities with reason. Faced with the same confrontational logic, Zhai Minglei’s first words to his own interlocutors last week re-iterate that he is not an enemy.

The following is a translation of Zhai’s exchange last Friday with officers from the Cultural Sector Enforcement Squad. The entry was posted on his personal blogpaper, Yi Bao, which Zhai continues to maintain:

An Unforgettable Night

On the morning of the 29th, five people from the Cultural Sector Enforcement Squad (文化市场执法大队) paid a visit to my home and took away my hard drive and copies of the magazine. To guard against the unforeseen, I went to an internet bar and sent an urgent message to a friend, asking him to post it on Yi Bao. I suppose I was thinking that if things got worse that would be my goodbye to readers.

That afternoon and evening I received more than 40 phone calls and short messages from friends and fellow journalists.

Haipeng was the most amusing. As soon as he opened his mouth it was: “Ah, Minglei, don’t go and do this Minjian — do a pornographic magazine instead. Look, I had a word with the head of the squad and told him you had a bunch of ancient Chinese pornographic art stashed away at your place, and it would be a lot less trouble if they went after you for that. As a prize for informing against you they’re going to give me a post as number two at Wenhui Publishing … ” Before long, he called again. He was clearly trying to get me to relax.

When Wang Keqin called it was with a strand of strange laughter. “Ay, Brother,” I said, “How is it that you’re laughing up your sleave when I’m beset with troubles?”

“I never thought the axe would fall on you, my chubby friend!”

“Yeah, I know,” I said, “I’m the least combative one in our circle!”

“Ha ha. So, have they found any gold bullion yet?”

“No, but they did find the sword Chiang Kai-shek gave me.”

“Well, I didn’t call last time you were shut down, so I thought this was a rare opportunity to call and express my condolences.”

When I heard Wang’s great big laugh, I felt like there was nothing on earth to worry about.

“Hey there, Matador,” another old friend began when they called.

“What matador?” I said. “Fighter of dogs, more like it.”

It’s funny, but the first thing I think of with all of these friends in support of me is that shady third party [i.e., the authorities].

There are other calls etched in my heart.

After that came a lot of calls for interviews, from as far away as Spain and as near as Hong Kong. When it was time to sleep I was tired but couldn’t settle down.

Thoughts kept running in my head: Running Minjian, being shut down, doing Yi Bao online, being blocked, and now my hard drive gone so I can’t even write with my computer. If I must, I’ll take my pen out onto the streets and scribble on the walls.

At 3:30 in the afternoon on the 30th I was talking with a couple of old guys from the enforcement squad. According to their way of talking I was ‘accepting questioning and cooperating with the investigation’.

First, I said a few things: “You guys are enforcement, and you’re my antagonists, but we are not enemies. In my 13 years as a journalist I’ve criticized many people, and some of these have later became my friends because of that criticism.”

“I ask that you please let those men pulling the strings behind the scenes know that I thank them for their help in making my journey toward winning freedom of speech and press. And now that I’ve started I won’t stop. As a veteran journalist with a calling I will not rest until I’ve reached my goal. And that goal is to rehabilitate Minjian, to make clear that it is not an illegal publication. Please also thank them for opting for these comparatively civilized tactics, even if this began with a rather undignified raid of my personal residence.”

“I ask that you inform me of what organization you are from, and as you are not police, what legal grounds you have for searching a citizen’s place of residence.”

(After this my lawyer informed me that now even police need a warrant to search the residence of a private citizen. With only a Certification of Illegal Publication (非法出版物鉴定书) the Cultural Squad cannot enter a private residence. Thinking back now to that morning I realize that those five men standing in my doorway did not express any intent whatsoever to search my home. They said only that they wanted to come in and talk, and only then did I allow them in. After that they searched everything, including the paper for my printer. Is that not false pretenses? Afterwards, when my wife asked why a policeman had come along with them — this policeman never came in) — they joked and said, “We have to have police along for all our enforcement activities. They’re afraid you’ll pull knives on us.”)

I pointed out that the determination Minjian was an illegal publication violated the constitution. As soon as they heard that they cut me off. That was a question about the system, and we didn’t need to talk about that, they said. Do with it what you like, but I’ve got to say it, I said. Article 35 of the constitution says that citizens of the People’s Republic of China enjoy freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly and of demonstration. The constitution defines the boundaries between the government and civil rights and is the highest law of the land. You have entered a private resident bearing only a publishing ordinance from the State Council — and, notice, that this is a regulation, only a regulation, NOT a law passed by the National People’s Congress. That ordinance says: publications that are not approved … are illegal publications. As to who must approve, what agency must approve, it says nothing. Is there not a contradiction here between this approved publication and the freedom to publish? This is where our grief lies, and it’s a problem for you too [because your enforcement actions are based on a contradiction]. We don’t have a press or publishing law, and you guys can enter people’s homes holding just an ordinance and violate their private property! The constitution guarantees citizens the right to publish, and the government prevents it. In advanced nations, publishing licenses are there for the taking. There is not need for approval! But even if this ordinance from the State Council stands, Minjian is not in violation. We have approval from Sun-Yatsen University, with more than 20 public seals.

They said to me: “Now, now, let’s not get carried away!”

I said, “Besides that, we were circulated internally. Please show me the regulation that says internal materials require a publishing license. When authorities in Guangzhou did a search they were bearing a document from Guangdong provincial authorities saying ‘printing and reproduction of books, periodicals, audiovisual materials, etc, for internal use without prior approval from administrative offices dealing with publishing’ is illegal. Well, does Shanghai have this sort of decision on record?

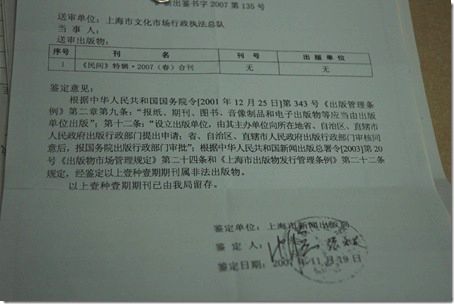

They said: “Whether or not it is an internal publication is not for you to say.” I responded: “Nor is it decided by you.” They said: “We are acting with the approval of authorities.” Then they pulled out a document from the Shanghai Administration of Press and Publications (上海新闻出版局) signed by Zhang Yongfa (张永发). On it was the following passage:

“According to the State Council’s Publishing Management Ordinance (of December 25, 2001, No. 343), Clause II, Article 9: Newspapers, periodicals, books, audiovisual materials and electronic publishing must be published through a [designated] publishing unit.”

“According to Article 12: The set up of a publishing unit must be approved by the publishing agencies of the people’s government of the relevant province, autonomous region or municipality following application by the sponsoring institution (主办单位).

“According to Article 24 of ‘Regulations on Management of the Publishing Market’, No. 20, 2003, issued by General Administration of Press and Publications (GAPP) of the People’s Republic of China, and Article 22 of ‘Shanghai Municipal Ordinance on Management of Circulation of Published Materials’, we determine that the following publication is an illegal publication.”

I laughed out loud. “Exactly what office of GAPP is this? I’ve heard that in Guangzhou there is some so-called Publications Authorization Committee (出版物鉴定委员会). It resembles a religious inquisition, and if this group of guys decides your an illegal publication, then you are.”

I emphasized again that Minjian was an internal academic publication put out by a university, that it was nonprofit and had no content of a reactionary, religious, political or pornographic nature. Whatever regulation they were trying to nail us with, it didn’t apply.

I asked for a copy of this document and they refused, so I took a picture:

“You use an order from an invisible office to limit freedoms. You say it proceeds from China’s unique character and situation (中国国情), and that the Chinese people must respect it. Well, foot-binding is also a product of China’s unique character and situation — should we bind our feet too?”

“Look, we’re not out to get you,” they said.

“I’m not afraid if you’re out to get me. My letter to Minjian readers was a personal statement I made out of conscience as a journalist.”

They eventually admitted that I wasn’t an editor acting on my own, but that I was hired by a university. I said that any questions concerning the content [of Minjian] could be addressed to me.

“Why do you insist on carrying this rotten potato all by yourself?” one of the officers said.

“What are you saying? Minjian is a publication with dignity, not a rotten potato. It would be more appropriate to call it a hot potato.”

This guy said: “We’ll give you three ways out … ” And I broke in, saying, “I’m not a criminal, I don’t need your way out!”

Then I showed them four documents of proof stamped by Sun-Yatsen University and demanded they return my hard drive as they had arranged for the day before. Much to my surprise, they refused. I was furious. I had my reasons, so I stood firm. “You’re not living up to what you promised,” I said.

In the end they referred the matter to their superiors and compromised, saying they would return my hard drive after they had confiscated all of the materials concerning Minjian.

In my anger I said, “This damned kid!” Later I apologized to the guy for this. Through the whole process I rationally defended my rights, dealing with matters not with men.

Because they had entered my home and confiscated all copies of 10 issues of Minjian I had saved, this meant they might deal with me more severely [having more physical evidence against me]. One of officers joked, saying: “Guangzhou fined you 30,000 yuan, so we’ll fine you 300,000.” I laughed out loud: “Money is the root that feeds me, so you might as well take my life.”

The way I see it, things could get rough for me, and this might even mean jail time. But even if it means giving up everything I have, I’ll continue this precious journey toward freedom of expression. I have no idea what’s in store for me.

If I go to prison for my words (坐文字狱), I won’t be the first, nor will I be the last — but I can make it mean something.