By QIAN GANG

Keyword: Scientific View of Development

On July 11, 2012, the South China Morning Post ran a report about how training materials for police in Hong Kong were found to contain Communist Party political slogans. One of the watchwords apparently included in the materials was the “Three Represents,” or sange daibiao, the political concept associated with China’s former president, Jiang Zemin. News of the training materials spread rapidly on the Internet, and many Hong Kong locals were dismayed to learn that police in the territory were being subjected to “brainwashing.”

Lately, nerves in Hong Kong have been especially sensitive to perceived encroachments from Beijing. And concern about the Party’s political slogans seeping over the border may be understandable. But the fact is that officials in China today would scratch their heads if you asked them to list out the “Three Represents.” Assuming the police training materials in Hong Kong were really intended to “brainwash,” I don’t envy the author’s daunting task of explaining what the “Three Represents” are all about.

This phrase, in fact, leads us into the mysterious core of what I have called the Party’s “general lexicon,” the idea of the ideological banner, or qihao (pronounced “CHEE-how”).

All four generations of Chinese Communist Party leaders have had their own ideological banners. These symbolize a leader’s contributions, which could be called their political philosophies, except that qihao are often far less material or definable than that suggests. Qihao are political brands, and like commercial brands they have an insubstantial quality that transcends their material (or practical) value.

Mao Zedong’s ideological banner is “Mao Zedong Thought” (Mao Zedong Sixiang). Deng Xiaoping‘s is “Deng Xiaoping Theory” (Deng Xiaoping Lilun). Jiang Zemin’s, once again, is the “Three Represents.” And Hu Jintao‘s banner, his brand legacy, is the “Scientific View of Development” (Kexue Fazhan Guan). Below are China’s four generations of top leaders and their respective qihao.

These ideological banners may seem inconsequential, flapping about in China’s political winds. But Party leaders regard them with great seriousness, and their symbolic importance is reiterated in every major document or speech:

. . . raising high the glorious banner of socialism with Chinese characteristics, guided by the important ideologies of Deng Xiaoping Theory and the ‘Three Represents’, [the Party] thoroughly implements the Scientific View of Development . . .

The above phrase is perhaps the most standard expression of political correctness in contemporary China. It brings in (as it must) all three of the prevailing ideological banners of the Chinese Communist Party.

To a large extent, understanding the 18th National Congress begins with an understanding of these qihao. What do they mean? How do they emerge?

Mao Zedong Thought is a qihao that the Maoist left of China’s political spectrum regards as its quintessence. At the end of the Cultural Revolution, the Chinese Communist Party engaged in a limited criticism of the errors committed under Mao. Mao Zedong’s ideas themselves were not repudiated, however. In fact, the Marxism-Leninism so central to Mao Zedong Thought remained ideologically intact and symbolically important.

In the 1980s, no new qihao were created within the Chinese Communist Party. It was only in the 1990s that Deng Xiaoping Theory strutted onto the stage. This new banner term reached its apogee in the political report to the 15th National Congress in 1997, following Deng Xiaoping’s death earlier that year. Deng Xiaoping Theory was essentially a revision of Mao Zedong Thought, upholding the intense concentration of power that marked Mao’s rule while at the same time promoting a capitalist economy. Most ordinary Chinese today see the policy of “reform and opening up,” or gaige kaifang, as emblematic of Deng and his ideas.

At the 16th National Congress, five years after Deng Xiaoping’s death, it was Jiang Zemin’s turn to shine. Even as he transferred power to Hu Jintao, Jiang’s own qihao, the Three Represents, climbed to its zenith.

The Three Represents demanded that the Chinese Communist Party “represent the developmental needs of China’s advanced production capacity, represent the forward direction of China’s advanced culture, and represent the fundamental interests of the majority of the people.” That is a mouthful. So it’s no surprise that many people seized on the much simpler idea — Jiang’s basic intent in all this sloganeering — of “letting capitalists join the Party.” A few commentators tried using the term “Jiang Zemin Doctrine” to describe his ideological legacy, but this never caught on. Jiang’s doctrine would not bear his name, a reflection of the fading notion in China of the paramount leader.

Once Hu Jintao had fully secured the reins as China’s national leader, becoming chairman of the Central Military Commission in 2004, he set about creating his own political brand. Known as the Scientific View of Development, Hu’s qihao rose to the top in the political report to the 17th National Congress in 2007. The Scientific View of Development was about sustainable, balanced and people-based development in China. This was understood essentially as a recognition that China’s growth through the 1990s had to a great extent been uneven, worsening tensions and divisions in Chinese society.

Like Jiang’s third-generation term, Hu’s fourth-generation qihao did not bear his name. But Hu’s authority as a Party commander was in fact a notch below that of his predecessor. In the Jiang era, major policy announcements typically began with the phrase, “The Central Committee united around the core of comrade Jiang Zemin . . . ” Hu Jintao has had to settle for a rather less potent preamble: “The Central Committee with Comrade Hu Jintao as General Secretary . . . “

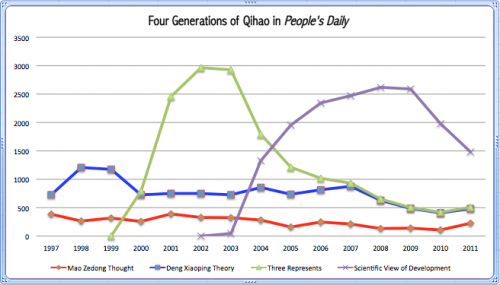

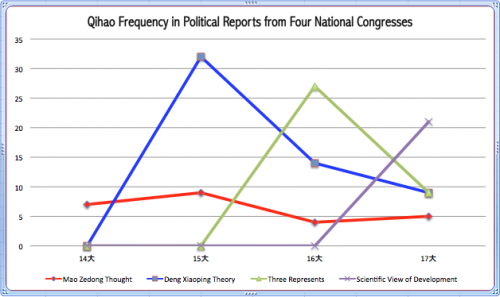

To sum up, when Jiang Zemin came to office in 1989, he solidified his power and standing first by raising up Deng Xiaoping’s banner, Deng Xiaoping Theory. Only after some time did he introduce his own banner term, which was passed on to his successor, Hu Jintao. More than a year after he came to power, Hu Jintao fashioned his own banner, the Scientific View of Development. But the following graphs illuminate one important difference in the life cycle of Hu’s term.

The first graph shows the four qihao as they have appeared in the People’s Daily since the late 1990s. The second graph shows the relative strength of these terms in the five official speeches given at the 60th, 70th, 80th, 85th and 90th anniversaries of the Chinese Communist Party. What we can see clearly here is that Hu Jintao’s term has gone into decline even while he is in office.

Uses of the Scientific View of Development in the People’s Daily fell steadily through 2010 and 2011. And when we compare the official speech given at the Party’s 85th anniversary in 2006 to the 2011 speech to commemorate the 90th anniversary, we again see use of Hu Jintao’s term slipping. Deng Xiaoping Theory and the Three Represents also fell during this period, but Mao Zedong Thought rose slightly. Reading Hu Jintao’s speech for the 90th anniversary, I speculated in the Hong Kong Economic Journal at the time that the weakness of Hu’s Scientific View of Development probably meant there was little hope that his qihao would figure prominently in the political report to the 18th National Congress in 2012.

During the first half of 2012, there were 571 articles in the People’s Daily that used the Scientific View of Development, down substantially from the same period in 2011. But as the 18th National Congress drew closer this year, Hu seemed more intent on raising the pitch of his legacy term.

On July 23, 2012, Hu Jintao delivered a speech at a special forum attended by provincial-level leaders. In this speech, the relative frequencies of the four Party-banner terms were different from what we saw in his 90th anniversary speech. Mao Zedong Thought was mentioned just once, while Deng Xiaoping Theory and the Three Represents were each given three mentions. The surprise was Hu’s Scientific View of Development, which came in with six mentions (plus three additional mentions of the shortened term “scientific development”).

In his speech, Hu Jintao resoundingly affirmed China’s accomplishments in the decade since the 16th National Congress, saying it had made “historical achievements and progress” chiefly because of the “formation and implementation of the Scientific View of Development” under the guiding ideas of Mao, Deng and Jiang.

Hu Jintao’s exact words were:

The full and serious fulfillment of the Scientific View of Development remains a long-term, difficult task, and it faces a range of tensions and hardships that will be very challenging. We must, with greater resolve, more effective measures and an improved system, fully implement the Scientific View of Development. [We must] truly transform the Scientific View of Development into a powerful force driving the better and more rapid development of our economy and society.

In the wake of Hu’s speech, the People’s Daily ran a series of articles explicating it — explaining its “spirit,” as this is called in Party jargon. On July 31, 2012, an article called “Deeply Grasping the Major Importance of the Scientific View of Development” offered a detailed review of Hu Jintao’s qihao. One week later, on August 6, People’s Daily Online ran an article by Liu Yunshan, the Party’s propaganda chief. The article said China must “more conscientiously take the road of the Scientific View of Development.” This wave of pro-Hu propaganda suggested that the Scientific View of Development was not just a “guiding principle,” or zhidao sixiang, but in fact was a fundamental policy to be put into full effect for the foreseeable future, even in the face of “hardship.” The context — and let’s not forget how sensitive the Party is to context — implied that the Scientific View of Development is a policy that will define how China handles its business for the next 10 years.

The Scientific View of Development symbolizes Hu Jintao’s political power. Affirming this term means affirming Hu’s 10 years of leadership; strongly emphasizing it signals his lingering influence. For this reason, we can look at how the Scientific View of Development appears at the 18th National Congress as an important indicator.

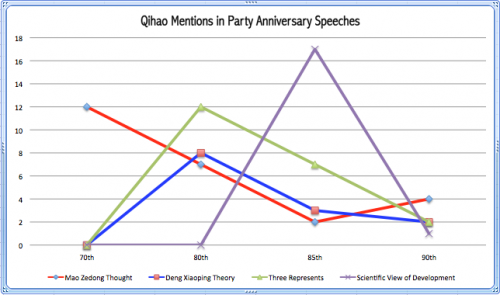

The Chinese Communist Party has held four national congresses since the June 4, 1989, crackdown on democracy demonstrations in Beijing. When we plot the number of times the four qihao are used in the political reports to those congresses, this is what we come up with:

We can look at the fate of Jiang Zemin’s banner term for clues to what is in store for Hu Jintao’s Scientific View of Development. Jiang presented the Three Represents late in his term as president, and he passed the term on to Hu Jintao. During Hu’s first two years in office, the Three Represents remained influential. In 2004, Jiang’s qihao was written into the Party Constitution (think of it as the Party’s watchword hall of fame), just as Deng Xiaoping Theory had been written into the Party Constitution in 1999. On September 19, 2004, just as Jiang Zemin was handing his chairmanship of the powerful Central Military Commission over to Hu Jintao, a meeting of the Central Committee issued a “Decision” on strengthening the Party’s “governing capacity.” That decision formally introduced the Scientific View of Development. From that time on, Jiang Zemin’s qihao faded while Hu Jintao’s burgeoned.

There is an old saying in China: “When people leave, the tea grows cold.” This really is the case for the ideological banner terms that symbolize the legacies of China’s Party leaders. Deng Xiaoping Theory, the Three Represents and the Scientific View of Development — these are all cups of tea sitting on the conference table of Chinese politics.

When the curtain opens on the 18th National Congress, where will these banner terms stand? Will Hu Jintao be able to do as Jiang Zemin did, passing his qihao on to the next generation of leaders? If so, how far will his successors carry the banner before it falls? When will his successor, whoever it may be, introduce their own political brand (their own cup of tea) to the world? And what kind of qihao will that be?