As the debate over constitutionalism rages inside China, the China Media Project is pleased to announced the publication (or re-publication) of Heralds of History (历史的先声), a book that documents the articles and speeches that defined the Chinese Communist Party’s push for freedom, democracy and constitutionalism in the 1940s.

The book, edited by CMP fellow Xiao Shu (笑蜀), was first published in China in 1999, but was quickly banned by the authorities. It is an authoritative collection of speeches and articles outlining the CCP’s core goals and political beliefs from the early 1940s through the end of the war of resistance against Japan in 1945.

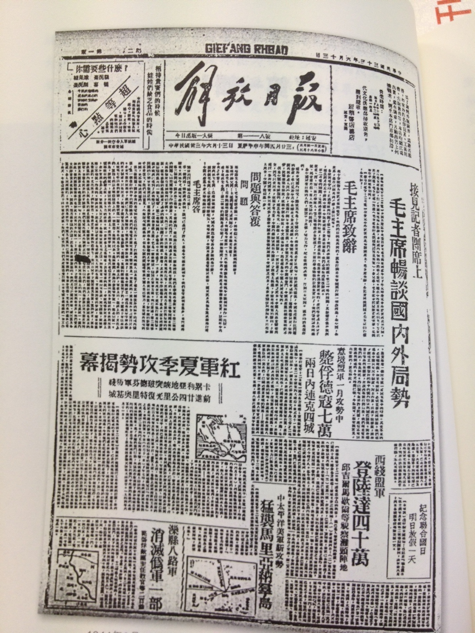

For example, there is Mao Zedong’s June 13, 1944, article in the Party’s Liberation Daily, in which the first paragraph from the “great helmsman” reads: “China has shortcomings, many shortcomings in fact, and the greatest of these, in a word, is that it lacks democracy. The people of China are in dire need of democracy, because only with democracy can our war of resistance have strength, can our internal and external relations be right . . . can we build a good nation — and only democracy can ensure unity in China once war has ended.”

[ABOVE: Front page of the July 13, 1944, edition of the Chinese Communist Party’s Liberation Daily newspaper, with article from Mao Zedong on democracy on the right.]

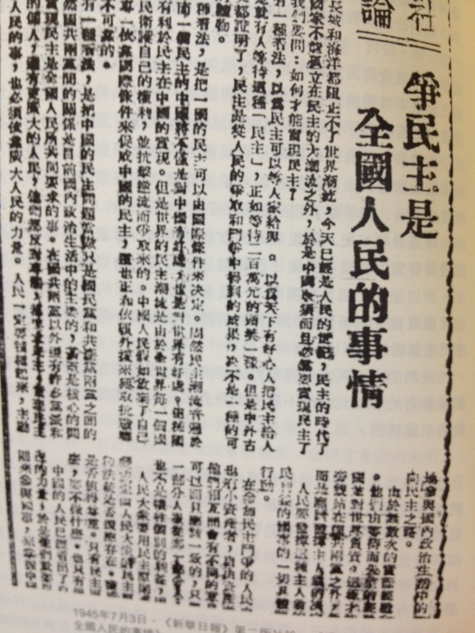

Then there is the July 3, 1945, piece in the Chinese Communist Party’s Xinhua Daily, the headline: “Fighting for Democracy is Something for All the People of the Nation.” “[T]his is already the century of the people,” the piece begins, “the age of democracy, and no country can stand alone outside the great democratic tide — so China must, and must urgently, realize democracy.”

[ABOVE: Front page of the July 3, 1945, edition of the Chinese Communist Party’s Xinhua Daily newspaper, with article on the need for democracy.]

Xiao Shu’s book, published by the Journalism & Media Studies Centre, is absolutely essential reading. You can purchase the book at Cosmos Books in Wan Chai or Kowloon.

But don’t take our word for it. The following is a review of the book — placing its publication nicely in the context of the current constitutionalism/anti-constitutionalism storm — in today’s Lianhe Zaobao. The review is written by Wu Wei (吴伟), a scholar of modern Chinese history who in the 1980s was a researcher at the Office of Political Reform of the CCP Central Committee, and served as secretary to the office’s director, Bao Tong (鲍彤).

“The CCP Should See its Political Promises of Yesteryear as ‘Positive Assets'”

Wu Wei (吴伟)

Lianhe Zaobao

Heralds of History, edited by Mr. Xiao Shu, has recently been reissued in Hong Kong. This book was first published in China in 1999, and at that time it bore the subtitle: “Solemn promises made a half century ago.” Perhaps it was this subtitle that touched on sensitive nerves, causing the book to be repeatedly banned, so that to this day few Chinese have ever heard of it.

A promise is the word of a trustworthy person that ensures something will happen. The political promises of a ruling party are this ruling party’s clear declarations of political attitude, political goals, a political contract made with the people of a nation in exchange for support and authorisation. They also amount to a political consensus reached with the people of the nation. They contract and define this Party’s future political actions, forming the basis of political power and legitimate government. And whether it abides by its political promises is a basic measure of the party’s political organization, its governing morals and political ethics.

Way back during the war of resistance [against Japan] in the 1940s, the Chinese Communist Party, as a “friendship party” with the ruling Kuomintang Party, issued a series of demands to limit the one-party dictatorship of the Kuomintang, calling for the implementation of democratic constitutionalism, initiating and leading a social movement to achieve democratic constitutionalism in China. Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai and other leaders of the Chinese Communist Party, the Liberation Daily, Xinhua Daily and other CCP media issued a torrent of discussions and articles criticizing the Kuomintang’s fascist formula of “one political party, one doctrine, one leader” (一个政党,一个主义,一个领袖). They expounded comprehensively on the supreme importance of democratic constitutionalism, freedom, equality, love for humanity and human rights for China’s political development.

Heralds of History includes a segment from Zhou Enlai’s 1944 “Address Concerning Constitutionalism and the Question of Unity” (关于宪政和团结问题的演说), which represents the Chinese Communist Party’s political demands at the time: “We believe that if we desire to achieve constitutionalism, we must first achieve a number of prerequisites of constitutional reform. We believe the most important prerequisites are three: the first is to ensure democracy and freedom for the people; the second is to lift the ban on political parties; the third is to exercise local autonomy. The people’s freedoms and rights are many, but right now what all the people need most urgently is freedom, freedom of residence (人身居住), freedom of assembly and association (集会结社的自由), freedom of speech and the press (言论出版的自由).” These calls and demands were a political declaration made against the dictatorship of the Kuomintang. They were solemn promises made by the Chinese Communist Party about the political goals it would pursue once it achieved political power. And they were the source of the serious care and support shown to the Chinese Communist Party by the masses and by various other democratic parties.

At a political conference held after the victory [in the war against Japan], through the combined effort of the Chinese Communist Party, the Kuomintang and other political parties, and through a process of political consultation, a draft emerged for a Western-style constitution. Even though the draft later failed, people could see that the Chinese Communist Party and other parties were working towards democratic constitutionalism. Later, as the Kuomintang struggled both politically and militarily to maintain authoritarian rule, these promises to realize democratic constitutionalism, to realize the dream that “farmers have land to till”, earned the Chinese Communist Party the broad political support and social foundation it needed to achieve political power — and in 1949 it won leadership of the entire country.

A half century has passed . . . but the CCP that gained political power has not truly fulfilled those promises it made back at that time. While China today does have a constitution, it does not have constitutionalism; while it has the words “republic,” what it has in effect is a one-party authoritarian system of exactly the same kind the Kuomintang had back at that time.

. . .

This book edited by Xiao Shu again raises those promises that the Chinese Communist Party made those many years ago. It lets the people of China know that the Chinese Communist Party of more than a half century ago was a political party in pursuit of democracy, that had pointed out a broad road for the development of the Chinese people. This book is a “positive asset” for the Chinese Communist Party, allowing it to protect and grow its wealth. Realizing these promises is China’s historical responsibility, and also the hope of the people of China. Only be realizing these promises can the Chinese Communist Party continue to preserve the basis for its leadership.

The problem is that there have always been people within the Chinese Communist Party who have spurned these promises. More than ten years ago, this book edited by Xiao Shu was banned entirely in mainland China. After the 18th National Congress [in November 2012], General Secretary Xi Jinping declared: “The life of the constitution is its implementation; the power of the constitution is in its implementation.” He talked about “raising the full implementation of the constitution to a new level.” He said also that [the Party] “must strengthen checks and monitoring of the exercise of power, putting power in the cage of regulation.” Just as most normal Chinese were celebrating this, thinking a beautiful “Chinese dream” was about to become real, a number of mainstream [Party] media pushed a wave of anti-constitutionalism. They talked about how “constitutionalism is a political system belonging to capitalism,” that it was “a trap by which imperialism hoped to bring about the peaceful evolution of China.” The people who wrote these things all completely forgot that in those years the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party themselves initiated the move toward constitutionalism, that they continually praised American-style democracy, that they continually declared that the Chinese Communist Party must, after it came to power, “avoid one-party authoritarianism at all costs,” “not allow one-party rule of the country.” Of course, not everyone has forgotten the promises, and some explain that this was merely a strategy at the time to gain political power. But that is tantamount to an admission that at that time the Chinese Communist Party used whatever means it could to deceive the people and gain political power, that it has no political morality or political ethics. So in order to deny constitutionalism, in order to deny the promises the Chinese Communist Party made in those years, some people are ready to push the Chinese Communist Party into a place without virtue, trust or justice, turning the Party’s governing legitimacy into a joke.

Yesterday, I saw Zhang Ming’s review of Xiao Shu’s book, in which he said he did not believe that the Chinese Communist Party was ready to simply toss out this period in its history, to write off the constitutional movement of its leaders. While I too don’t believe, I do feel uncertain. On the one hand, because of this anti-constitutionalism wave we are seeing. And on the other hand because it is as Zhang says, that realizing these promises and “accepting this legacy means a complete rebirth through political reform. This kind of reform is something the Kuomintang could not do when it governed China, but can today’s Chinese Communist Party do it?” I have little confidence.