It’s that time of year again. No, I don’t mean the Nobel Prizes. I’m not talking about the International Emmys. It’s time for the World Media Summit.

You know, that buzzing international meeting to carry on serious strategic dialogue about the future of media at the pleasure and expense of China, the country with the world’s most robust system of media controls. Or, as it is better unknown to all, the media event all major global media players attend but none bother to actually cover. Why not? Because under the surface it’s all just a little too disgusting.

For those of you not familiar with the World Media Summit — because only Chinese media have covered it (enthusiastically too) — here is how the state-run China Central Television describes its impetus and origins:

During the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, President of Xinhua News Agency Mr. Li Congjun respectively held working talks with the leaders of the global major media such as News Corporation, The Associated Press, REUTERS, Kyodo News, BBC, etc., exchanging the views on the challenges of the digital multi-media era, enhancement of exchange, cooperation and win-win, etc. All the parties reached consensus that it is necessary to hold the World Media Summit, which builds an efficient platform for the global media to communicate with each other and pool collective wisdom, sparking their thoughts and wisdoms, discussing survival and development, and talking about cooperation and future.

From 8 to 10 October 2009, the World Media Summit was successfully held in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. This summit was jointly initiated by nine global leading media organizations in the world – Xinhua News Agency, News Corporation, The Associated Press, REUTERS, ITAR-TASS, Kyodo News, BBC, Turner Broadcasting System and Google Inc., and organized by Xinhua News Agency, which absorbed the leaders of more than 170 media organizations from across the world.

So, this was a more or less spontaneous meeting of the big guns in global media, “jointly initiated” by “nine leading media organisations.” Because a bit of shoptalk among global media leaders could be a very productive thing. “Survival” is at stake, after all. And couldn’t we all benefit from the pooling of “collective wisdom”?

Well, not exactly. The Global Meeting Summit was, make no mistake, the idea of China’s leaders at the most senior level, the direct product of a specific media policy launched by then-President Hu Jintao in 2008 and designed to combat what China saw as its strategic failure of “discourse power” internationally. China wanted a bigger voice. And it wanted to influence all of the other voices talking (negatively, always SO negatively) about it.

What better way to close the gap than to get ALL the global media bosses around the conference table — and of course also around the dinner table?

At the helm of the summit since the beginning has been Xinhua News Agency chief Li Congjun (李从军), a member of China’s central party committee who was deputy chief of China’s Central Propaganda Department for over six years before he took on the top Xinhua job. In February 2009, eight months ahead of the first summit, Li wrote in China Journalist:

According to the central committee’s strategic demand for “strengthening outside propaganda/publicity” (大外宣), we must work hard to get our own voice out at the first moment from the actual scene for important news and sudden-breaking incidents . . . constantly enhancing the affinity, attractiveness and infectiveness of Chinese news reports to the outside world, actively seizing the initiative and our right to have a say in international public opinion channeling, working to create an objective and amicable international public opinion environment. . .

[We must] actively seek out new horizons, new mechanisms, new channels and new methods in the area of outside dialogue and cooperation, particularly, as by the demands of central party leaders, successfully organizing the first meeting of the World Media Summit, building a platform for dialogue among first-rate international media (国际一流媒体), further raising the capacity of Xinhua News Agency to make its voice heard in the international news and information sector.

So . . . To sum up, the World Media Summit, this ostensible back-slapping affair offering an opportunity for media leaders to talk media strategy, is fundamentally about China projecting its influence over global media agendas. Any global media bosses at the summit who do not realize this — though I suspect plenty of them do — are woefully deceived. I want all of you participants at the World Media Summit right now to pick up your complimentary Xinhua News Agency fountain pens and write this on the back of your hand: “I am not here because China really wants to talk about the future of global media. I am here because China wants to channel the future of global media.”

I realize I’m laying the sarcasm on thick. But I’ve written with some seriousness about the World Media Summit since its first “presidium” in 2009, and one of the things I find most incredible is that there are virtually no news reports of the event anywhere outside China. This is an international summit about media, hosted by a country that has an abysmal record this year alone on media and information (including the crippling of Sina Weibo, its most vital media platform), and no one wants to talk about it.

Is this not news? Well, let me help out by providing a list of three interesting possible stories emerging from this year’s summit:

1. According to reports from Chinese state media, next year’s World Media Summit will be hosted by the New York Times. Why? What does this mean? How is it linked, if at all, to the business interests of the New York Times in China? What does the New York Times have to say for itself?

2. On the World Media Summit agenda this year is the feasibility of creating new global prizes for journalism. How would the media groups involved in these future prizes through their summit participation balance their professional goals and values against attempts by China’s leadership to use the prizes to push its own values? If the prizes had been awarded this year, would David Barboza have been considered for his Pulitzer Prize-winning report on the family of former Premier Wen Jiabao?

3. As media bosses wine and dine with Xinhua News Agency chief Li Congjun, they might like to know that Li wrote last month in the official People’s Daily that “[the Party must be] confident and courageous in its positive propaganda, [carrying out] the public opinion struggle with a clear banner.” His article was one of the most hardline pieces on the CCP’s press control priorities to appear in China in recent years. He spoke in extreme terms of the attempts by Western media and “hostile forces” to Westernize China. “This again sends a warning to us,” he said, “that strengthening [China’s] international discourse power is of urgent importance.”

Participants should know that this — the strengthening of China’s discourse power — is the real reason they have been invited to the World Media Summit.

Li’s words are more than just rhetoric. They are another sign among many in recent weeks of a very real crackdown on speech and civil rights in China. You can read up here on the arrest of Liu Hu, a journalist with Guangzhou’s New Express. Or maybe brush up on the recent arrest of a middle school student accused of spreading rumors on social media.

But don’t let the news spoil your dinner.

_________________________________

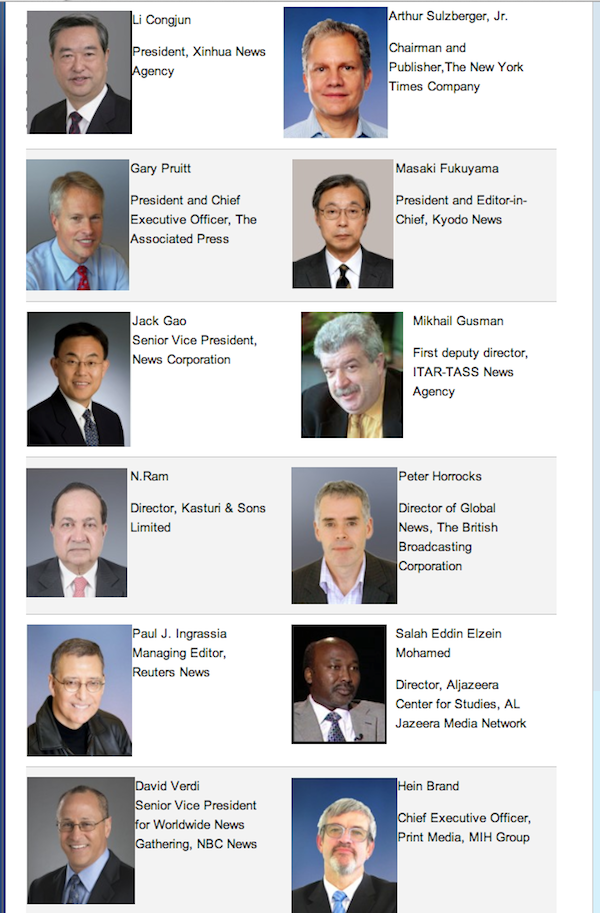

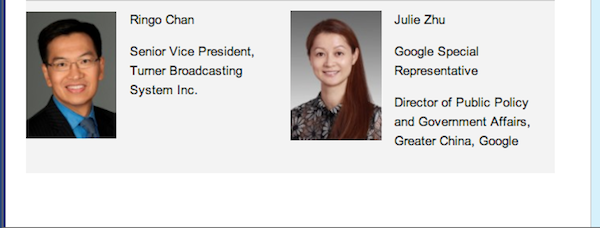

And for those who are interested, here are your global media representatives: