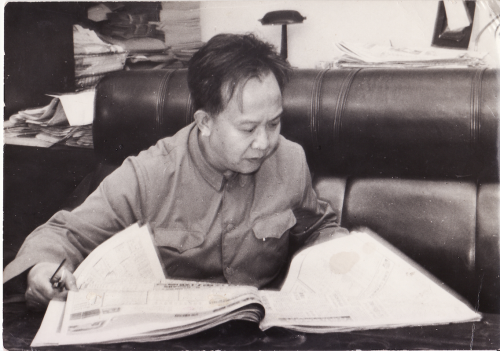

Tomorrow, June 27, the China Media Project will launch its latest Chinese-language book, a memoir by Southern Weekly founder Zuo Fang (左方).

The book, which begins with a fascinating personal perspective on such historical events at the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, tells one insider’s story of the birth and development of one of contemporary China’s most influential newspapers.

Readers can find more details about the event below. But here’s a little taste in translation of Zuo Fang’s book, from a section called “Three Journalism Teachers” (新闻业的三个导师).

My work in the media spanned a period of 36 years, and during that time I had three teachers. One was Huang Wenyu (黄文俞). He was a newspaper man of the intellectual sort, and he had a substantial impact on my ideas. At Nanfang Daily before the Cultural Revolution a major meeting of editors was held once a month. I would see Huang Wenyu up on stage, smoking cigarettes one after the other, spending up to two hours talking about the strengths and failings of our reports over the past month, and laying out our work for the coming month.

Huang quipped that he was the king of his own small country. The [paper’s] affairs all turned on him alone. But for some time I was perplexed. I would see Huang Wenyu return to the newspaper’s offices and head straight into his office. He never visited the different departments. So how could he possibly have a grasp of what was really happening at the newspaper?

Eventually, I figured it out. At home, in fact, Huang Wenyu had really decent tea as well as a television set given to him by the provincial television station. Every weekend and on Sunday evenings, mid-level editors from the paper would visit Huang at home. They would sip tea, watch television and chat. This was the secret of how he managed to keep astride everything happening at the paper.

Everyone at Nanfang Daily referred to him as “Wenyu.” Only on formal occasions would people append the title “comrade.” Nanfang Daily followed the Soviet model of newspaper publication after the Liberation in 1949. But as far as interpersonal relationships went, the intimate comrade-in-arms relationships of the war-time period still held — and this became a fine tradition at Nanfang Daily.

At that time, the editorial board of Nanfang Daily was under the direct control of the provincial party secretary, and Huang Wenyu was able to attend meetings of the provincial standing committee. Officials in the provincial propaganda department were not on the standing committee, so they could not control Nanfang Daily. . . .

[Much later] when Huang Wenyu was sick and in the hospital, I went to visit him and told him about the four guiding principles of Southern Weekly. Of the four, I said, three of them came from him, and only one was of my own creation. “What four principles?” he asked.

The first thing is specialization (主攻) and a good grasp of feature stories (副刊主守). This is something I learned from you, I said. In terms of specialization, I haven’t yet accomplished a great deal. We have only eight pages so far, and we don’t have enough manpower yet to do in-depth, investigative reporting. In terms of features, I’ve made one small innovation — I’ve told my colleagues responsible for the features to not “edit them” but rather to “have fun with them.” When you “edit” a paper you make it about official business. But when you “have fun” with it you treat it like a miniature bonsai landscape, fussing over its beauty and fineness. There’s just one character’s difference between “editing” and “having fun,” but a gulf separates the two. Specialization is about drawing the reader in, and features are about holding on to them.

At this point, Huang Wenyu nodded his head.

The second thing is that while there may be truths that we cannot speak, we must never utter falsehoods. This is something else I learned from you. But here also I made a small modification. I’ve divided the truths we cannot speak into two kinds. There’s what I call the “hard thunder zone” (硬雷区) and the “soft thunder zone” (软雷区). I think we can actually make breakthroughs for the vast majority of things in the “soft thunder zone.” The “soft thunder zone” is where I’ve decided to concentrate the main force of the newspaper.

The third thing is something I created myself. I call it, “First make the bottle, then make the wine” (先做瓶, 后酿酒). The bottle is about the form of the news, and the wine is about freedom of speech. When we accept that there are truths we cannot speak, this means we’ve already to some degree relinquished our right to freedom of speech. We should place our emphasis on innovating the form of the news, doing away entirely with the falsehood, bluster and emptiness (假, 大, 空) of the Pravda model of newspaper publishing. We should fashion our own brand new form of language. Freedom must arise through form. The realization of freedom begins with form . . .

The learn about Zuo Fang’s fourth “guiding principle” for Southern Weekly, join us tomorrow, June 27, at Cosmos Books in Wan Chai. Details below. See you there!

Anyone interested is invited to attend the book’s launch, which will be attended by the author.

BOOK LAUNCH: How the Steel Was Not Refined (鋼鐵是怎樣煉不成的)

Co-published by the Journalism & Media Studies Centre/CMP and Cosmos Books

When: June 27 (Friday), 3:30-5:30pm

Where: Cosmos Books, No. 30, Johnston Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong

The event will be attended by the author, Zuo Fang, and other Southern Weekly veterans.

For more information, contact Cosmos Books at (852) 2823-9908, Ms. Zhang.

CLICK HERE to register online for the event, or call the telephone number above.

JMSC新書《鋼鐵是怎樣煉不成的》—— 左方與《南方周末》新書發佈會定於2014年6月27日(星期五)下午3:30至5:30在灣仔莊士敦道30號天地圖書公司舉行。

本書作者左方先生是中國內地最受歡迎的報紙《南方周末》創始人,他在書中回憶了跌宕起伏的人生歷程;對於中國當代史和中國傳媒發展史,這本書提供的第一手資料彌足珍貴。左方先生和多位南周元老將到會。

請與天地圖書網上報名:http://web.cosmosbooks.hk/Default.aspx?ID=1248