By David Bandurski — In the most recent, and final, issue of Far Eastern Economic Review, I wrote about China’s “soft power” campaign and its blindness to the more fundamental issues facing China’s global credibility. In an editorial in Hong Kong’s Apple Daily yesterday, Kong Jiesheng (孔捷生), a dissident cultural figure and writer of “scar literature,” offered his own views on China’s present obsession with “soft power.”

Kong writes about China’s “three afflictions,” or san’ai (三挨), which received some attention in 2008 following unrest in Tibet and in the run-up to the Beijing Olympic Games.

The idea, which Kong says emerged from a Chinese government think tank, is that three major factors over the past century have hampered China’s national strength — namely, foreign aggression, a weak economy and basic subsistence issues, and last, but now in the forefront, China’s continued demonization at the hands of proud, ignorant, hateful and fearful Western nations.

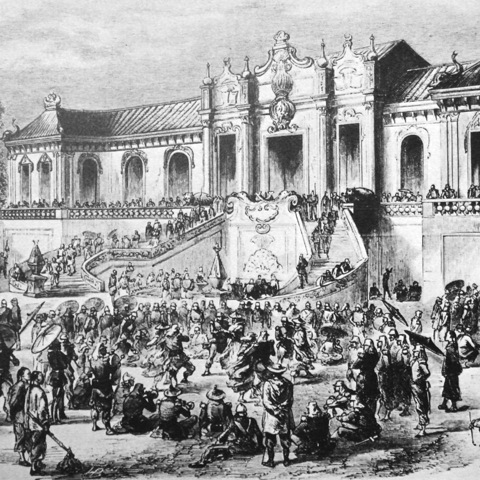

[ABOVE: Woodcut depicting the looting of the Old Summer Palace by Anglo-French forces during the Second Opium War in 1860. According to one formula explaining the past 60 years of CCP rule, foreign aggression was just the first of “three afflictions” suffered by China over the past century.]

The first of these afflictions was thrown off by Mao Zedong. The second by Deng Xiaoping. The CCP’s present generation of leaders now face the third.

The “three afflictions” is an interesting formula that can help us understand the thoughts and emotions driving current media policy in China. Specifically, the formula underlines the roots of the CCP’s present “soft power” push in the longstanding narrative of national victimization.

The first public mention of the term “three afflictions” seems to have come on April 15, 2008. An article by columnist Lu Ning (鲁宁), which appeared in the official Guangzhou Daily, in Legal Daily, and at numerous websites, including Hexun.com and China.com.cn, sought to explain the deep psychology of anti-China protests following the Tibet unrest in March 2008 and during the U.S. leg of the Olympic torch relay in terms of disfunctional Western jealousy over China’s rapid and peaceful rise:

There are some American and Westerners, including part of their mainstream media, who see China’s peaceful development as an offense to the eye. They trust overly in the hereditary advantage and moral superiority of Western values that have emerged over the past century, and when they assess China’s development and progress according to their double standards, they fail to understand, are envious, concerned and even frightened — how is it that Chinese have development so rapidly according to their own logic? Misunderstanding and envy, prejudice and fear — all of these are fine. But we Chinese have no need to fuss about it. For more than a century we have suffered from three afflictions . . .

Qiu Liben (邱立本), the editor-in-chief of the Chinese-language newsweekly Yazhou Zhoukan, also used the term in an August 2008 editorial on the importance of the Olympic Games for China, but Qiu emphasized the importance of real attractiveness, a core component of soft power:

If you wish to turn around this suffering of criticism (“挨骂”局面), you must do more than move others with emotion and reason. You must act justly, so that others admire you and adore you from the bottoms of their hearts. They must not simply ingratiate themselves with you for the sake of wealth and power. This is the human gold medal that the Chinese people truly yearn for, and it is the national prize of which modern China is in pursuit.

In yesterday’s editorial on media policy and soft power, Kong Jiesheng attributes the term “three afflictions” to the Sino-U.S. Research Center, a think tank under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

A translation of Kong’s editorial in Apple Daily follows:

Zhang Yimou’s Latest Film and the “New Three Character Primer”

I’m not so clear about the story line of Zhang Yimou’s new film, “A Simple Noodle Story,” but I do keep hearing about how terrible it is. Can Zhang Yimou really make anything worse than “Hero” and “Curse of the Golden Flower“? This is not inconceivable . . .

While I’m unclear about the specifics of “Noodle Story,” I do know that Qingdao had its own “three gunshot mystery” last year — and this offers sufficient proof that the facts of the real world are always stranger than fiction. [NOTE: The film title sounds very similar to the name given to the case of a suspicious death in Qingdao last year.]

It was reported that a huge swindler went missing in Qingdao after cheating people out of hundreds of millions, and his corpse was subsequently discovered with three gunshot wounds. Police in Qingdao launched an investigation and then wrapped up the case by concluding that he had “committed suicide.” Web users quickly had a field day with this — a suicide with three gunshots? Had he first tested the authenticity of his bullets on the thick hide of his ass? Where had he aimed the second shot? And perhaps, after all this trouble, the third shot had turned out to be a dud and a counterfeit? This is the real life version of “the three gunshot mystery” [“A Simple Noodle Story”].

I’ll turn now to the issue of the new three character primer (三字经). The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences is similar to the Imperial Academy (翰林院), and there are numerous research centers under the aegis of this “national think tank.” Mr. Huang, the head of Sino-U.S. Research Center, one of these [centers], is a new leftist, and it would seem more apropos to rename the center the “Center for Criticism of the US” (美国批判所).

It is the view of this Hanlin academician that this 60-year dynasty [of the CCP] has resolved what he calls “three afflictions” (三挨). Mao Zedong’s achievement was resolving the problem of China’s bullying [at the hands of foreign powers] (中国挨打的问题); Deng Xiaoping’s achievement was resolving the problem of Chinese subsistence (中国挨饿的问题); and now, in an era of peace and happiness, the problem of the dressing down of CCP rule [at the hands of foreign nations] (中共政权挨骂的问题) must be resolved.

This is about the universal values promoted by mainstream international civilization and about public opinion in the West directed against authoritarianism in China and its human rights record.

How is China to resolve this problem? The serious punishment rendered against Liu Xiaobo is a strong signal [of China’s stance]. China has risen to greatness, and it has no need to heed instruction from the West with its tail between its legs. It sees the three major human rights codes of the United Nations as so much dung and mud. What universal values? What mainstream civilization? Now is the moment for Beijing to grab hold of the discourse power and export its own value system. You dare to lecture me? Well then, I will say categorically that Liu Xiaobo will serve out his sentence. That game of “catch and release” we played with the West during the Jiang Zemin (江泽民) era won’t be replayed under the leadership of Hu Jintao.So what then is this Chinese-style value system? It is written plain as day in the judgement against Liu Xiaobo (刘晓波) — it is the “people’s democratic dictatorship and the socialist system,” and wherever Chinese citizens act against this or commit acts of “subversion,” wherever foreigners seek to criticize, this will not be stomached. You have the power to look after your own turf, but don’t fuss with my accounts, and don’t come begging for me to purchase your bonds.

There is another road to resolving the dressing down problem [of Western nations lecturing China], and this involves purchasing [global] discourse power by investing 40.5 billion yuan in a massive “external propaganda” (大外宣) campaign, all the while milking the Chinese people dry on human rights, welfare and the environment. It involves expanding “soft power” internationally. I remember more then twelve years ago when I had just moved into an apartment in Washington, D.C. Right nearby was a three-story red building occupied by Xinhua News Agency. I often watched the Xinhua expatriates come and go. They kept a low key, acting and speaking with utmost caution.

After some time, they wanted to expand the building, but this was refused by the American side because the property was too close to the Pentagon. At the time this even boiled over into an episode of anti-American resistance. The Americans asked rhetorically: are foreigners permitted to buy properties near Zhongnanhai and the Central Military Commission?

Back then you could hardly imagine today, when China Central Television has set up its U.S. bureau directly across from the White House. And I’m confident that the “monkey-snakes” (mouthpieces) coming and going do so with strutting confidence, not bothering to keep a low profile [NOTE: The Chinese words for monkey and snake together form a synonym of the word “mouthpiece”, or houshe.]. One need only look at rental prices at that address to understand the grandness and magnificence of Beijing’s “external propaganda” today.

But the real question is, can a nation’s soft power and discourse power be purchased in such a way?

[Posted by David Bandurski, January 5, 2010, 1:46pm HK]