The letter of self-confession was one of China’s most defining genres of writing in the 20th century, a “language of torture,” as Guo Xiaochuan’s daughter, Guo Xiaohui, later called it, by which those in positions of authority consolidate their power and assert the supremacy of their ideas.

In 1967, while China was in the throes of the Cultural Revolution, Chen Zaidao, a ranking general in the People’s Liberation Army, wrote with apparent frankness of his crimes and cravenness as he faced allegations of misconduct:

My ideas were slowly corrupted, my life eroding, my [work] style becoming rogue. When I saw my female comrades or nurses, I acted like a hooligan. I pawed them, not even behaving like a human being. I was degenerate and promiscuous.

Only Mao Zedong, the “Great Helmsman” at the tip-top of the power pyramid, could escape the writing of self-confessions. Deng Xiaoping, later the architect of market economic reforms in China, wrote quite a number himself. They included this one, dated August 3, 1972, addressed to Chairman Mao:

I have made a great many errors. These are laid out in my ‘personal statement,’ and I will not set them out again here. The root of my errors is the fact that my bourgeois worldview has not been utterly eradicated, and the fact that I have become estranged from the masses and the truth.

Likening the act of self-confession to “a first-person ‘struggle session’,” the poet Shao Yanxiang (邵燕祥) suggested the Soviet origin of the tactic was just part of the story. There were also precedents, she said, in China’s ancient imperial system and in the Republican era after the Xinhai Revolution of 1911, evidenced in the way “advisors, eunuchs and various Ah Q’s would strike their own ears and say, ‘The servant must die!’”

In Xi Jinping’s new confessional movement, there are shades of the Party’s troubled political past. Questions of guilt and innocence are subservient to the imperatives of political power.

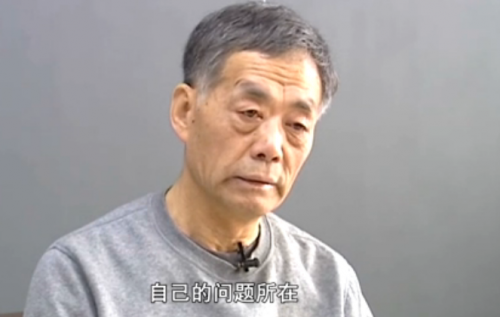

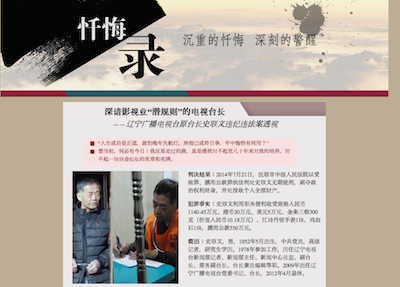

Shi Lianwen, the former television executive whose videotaped self-confession is now being promoted through the official website of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, may not be innocent. He stands convicted of clearly specified acts of graft, including the acceptance of cash payouts of 11.4 million yuan, about US$1.8 million, while he was director of Liaoning Television from 2009 to 2012. (Corruption investigators, with their penchant for peppering corruption-related releases with lurid and colourful details, have also said Shi accepted a valuable piece of bloodstone.)

But watch or read Shi Lianwen’s “confession” on the CCDI website, where it is part of a new multimedia feature series called “Records of Confession” (忏悔录), and it becomes clear that Shi’s primary crime is not the breaking of the law per se — rather, it is his betrayal of the trust and responsibility vested in him by the Chinese Communist Party.

The supremacy of politics and ideology over the law becomes oddly clear as Shi Lianwen confesses to having an overly commercial mindset in his management of Liaoning Television.

At the television station, I came to apply the “money” standard alone in determining the quality of the work produced by my comrades. I even put forward the slogan, “Not a cent can be lost within our business scope.” . . . While Liaoning Television did achieve influence, this was not by adhering to the cause of the Party but rather by serving the interests of various groups or individuals, through the service of small groups.

Media commercialization has been a part of de facto media policy in China since the middle of the 1990s. Over the past 20 years, Chinese media have moved boldly into the marketplace, spawning a whole new generation of magazines and tabloids that survive by being relevant to their audiences, and to those “small groups” of interest we call advertisers.

For all but a handful of core Party and government media — the likes of the People’s Daily and the official Xinhua News Agency — state support is a distant memory. The Party still places weighty political demands on the shoulders of the media, and censorship is a daily (or even minute-to-minute) concern. But without the “’money’ standard” for which Shi Lianwen is so contrite, without the succour of the market, media in China could not survive.

Does Shi Lianwen’s self-confession augur a change in the Party’s outlook on media commercialisation? Almost certainly not. The content of Shi’s confession, like the content of his alleged misdeeds, is largely irrelevent. It is the ritual and form of his confession that truly matters in the context of Xi Jinping’s mass-line reformation of the Chinese Communist Party.

As in the past, today’s culture of confession is not about accountability, clean government or a rules-based system. It is about dominance and submission.

Xi Jinping is China’s confessor-in-chief. You serve at his pleasure.

Read our translation of Shi Lianwen’s letter of self-confession on Medium.