THE DEATH over the weekend of Zhu Tiezhi (朱铁志), 56, deputy chief editor at China’s official Seeking Truth (求是) journal, has prompted soul-searching in Chinese chat groups — touching on issues at once personal, cultural, psychological and political. Discussion of Zhu’s death, which has led some to speculate a connection to the corruption case against former Hu Jintao advisor Ling Jihua (令计划), has quickly been scrubbed from most Chinese websites.

Regarded as an accomplished essay writer, Zhu first joined the Party’s Red Flag journal after graduating from Peking University in 1982 with a degree in philosophy. He joined Seeking Truth after rising to a senior position at Red Flag. Despite his involvement with these strongly ideological Party journals, however, Zhu contributed from time to time to other publications, including Guangzhou’s more freewheeling Southern Weekly newspaper. He was also a recipient of the Lu Xun Literary Prize, considered one of China’s most prestigious awards for writers.

On Sunday, June 26, the official China News Service ran a brief report on Zhu Tiezhi’s “untimely death” in the early morning hours, noting that “essay societies and writers across the country have expressed shock and grief.” In a blog post on the Caixin website, essay writer An Lizhi (安立志) praised Zhu for his contributions to the study and writing of essays, or zawen (杂文):

Those who research the essay have praised him as the soul of essay research; those involved in essay groups have praised him as a pillar of the essay profession; those who write essays have praised him as a friend and mentor. As the northern star of China’s essay profession, Mr. Zhu Tiezhi offered direction . . . and his starlight provided warmth and substance to the night sky.

[ABOVE: Zhu Tiezhi’s wife, Li Xinwen, appears during a press briefing at the State Council Information Office.]

Taiwan’s China Times reported that Zhu had “left behind a very ill wife and a lone daughter.” According to Hong Kong’s Apple Daily, Zhu Tiezhi’s wife is Li Xingwen (黎兴文), formerly chief of the publicity department at the Central Government Liaison Office in Hong Kong. Li, said the paper, “had a great deal of interaction with Hong Kong media, and was familiar with quite a few media people.” Li was also posted with the State Council Information Office in 2013.

Early unconfirmed reports that Zhu had committed suicide led to speculation in overseas Chinese media that his death might be related to the corruption case against Ling Jihua (令计划), the former political adviser to Hu Jintao who was formally charged earlier this year with accepting bribes. This speculation was driven by the publication in the December 15, 2014, edition of Seeking Truth of an essay (since removed) attributed to Ling Jihua in which he made 16 fawning references to President Xi Jinping’s speeches in an apparent attempt to curry favour. Rumours at the time suggested that Zhu Tiezhi had been responsible for green-lighting the piece, which came exactly one week before the formal announcement of Ling’s investigation.

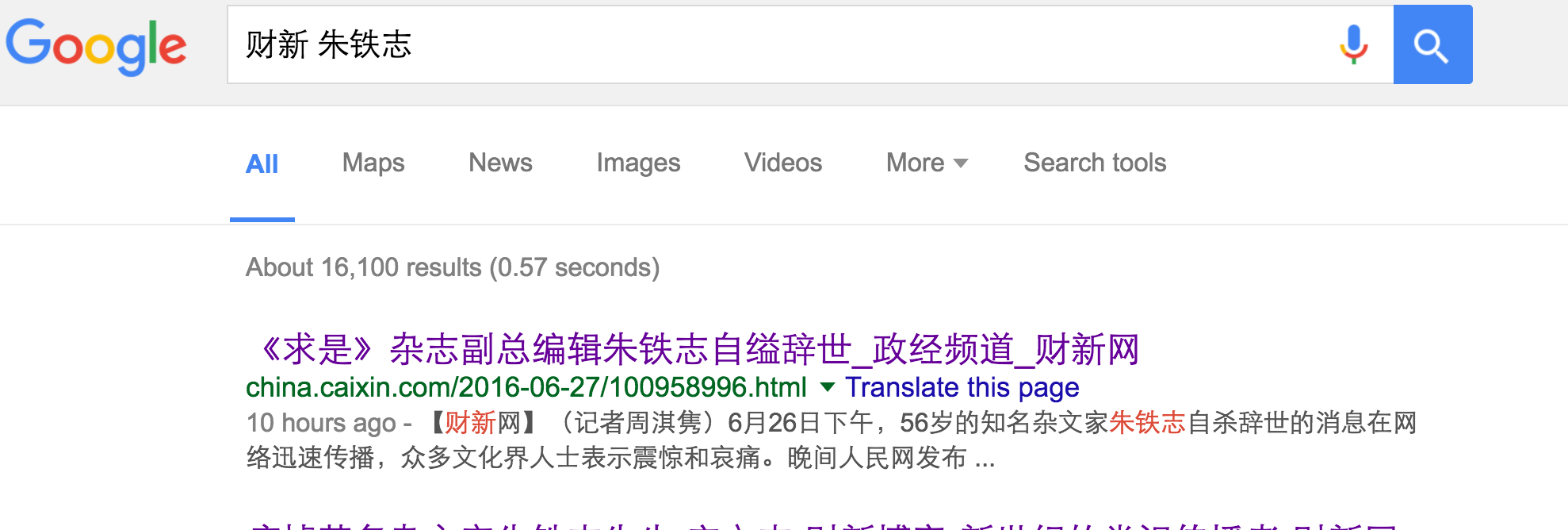

[ABOVE: Link on Google to a report on Zhu Tiezhi at Caixin Media that now yields a 404 error.]

A report since scrubbed from the website of Caixin Media reported yesterday that Zhu’s body had been found in the underground parking lot at Seeking Truth, and that there were signs that he had hung himself. That version of the story seems to be confirmed by an English-language report, citing the official China.org.cn, posted to the China Daily website early this morning. This report says that Zhu “was found hanged in a garage at his workplace on Sunday.”

But writers who knew Zhu Tiezhi were quick to discount the role of high-level politics in his death, saying he was known to suffer from chronic depression. Describing Zhu as a “faithful friend,” one former columnist for Southern Weekly said the reason for his suicide was almost certainly personal despair.

Zhu Tiezhi’s death recalls the suicide four years ago of Earth editor Xu Huaiqian (徐怀谦). At the time of Xu’s death, Zhu was among the first to share the news.

During his professional career, Zhu Tiezhi wrote often about the subject of death and euthanasia, as in his piece “If I Should Die” (如果我死), which has been re-shared on social media over the past 24 hours. Some of Zhu’s comments on the ethical and legal questions surrounding euthanasia are available here on the English website of the Supreme People’s Court.

Much of the discussion surrounding Zhu’s death has dealt with the complex emotional challenges of writing in China, where the necessity of political loyalty can erode a writer’s sense of conscience and self-worth. In a post deleted from Weibo, Chinese lawyer Zhou Ze (周泽) wrote: “Being an essay writer is ultimately about social conscience. To be able to serve as deputy chief editor of Seeking Truth — the internal lacerations would ultimately lead someone this way.”

In a report today, Singapore’s Lianhe Zaobao called Zhu’s death a suicide, and attributed it to “either depression or a gap between concepts and reality.”

. . . .

THE FULL circumstances of Zhu Tiezhi’s death will surely remain hidden from us. But we can to some extent — by looking at Zhu’s writings and the marked dissonance in tone and topic — explore the question of the “gap” to which Lianhe Zaobao refers.

Those of us who have followed the rousing language of news and propaganda policy in the Xi Jinping era propaganda will surely recognise the official tone of this piece, written by Zhu Tiezhi back in February this year:

[Xi Jinping’s] speech was directly at the three mainstream [Party] media, but even more at the front lines of national propaganda thought, and it is a programmatic document that directs news, public opinion, ideology and propaganda work for the Party and the government for the era.

As a publication of the central Party, and as an important battle position of propaganda and ideology, we at Seeking Truth bear the great responsibility of propagating the spirit of the series of important speeches by General Secretary Xi Jinping, and of propagating and explaining the Party’s theoretical line.

And in a piece for Seeking Truth last year, Zhu Tiezhi wrote about how the profusion of information in the new media age was transforming ways of life and making news and public opinion more important than ever before. “Under these circumstances,” he wrote, “how to deal with the media, and how to channel public opinion, has become an important question facing leading cadres at all levels.”

Zhu’s out-of-the-package official position in this piece is that Party and government leaders must work actively with the media, which after all are there to work alongside them:

Fundamentally speaking, our media are all mouthpieces of the Party and the government, all mouthpieces of the masses. They propagate the Party’s position, and at the same time reflect the calls of the masses — this is not only not a contradiction, but in fact is entirely unified. The people of the Chinese Communist Party must not have their own special interests beyond the interests of the people.

It is immaterial whether or not these sentiments were truly shared by Zhu Tiezhi. The fact is, we might find a thousand identical screeds from a thousand Party hacks, all of them effectively bylined “Party.”

But here is Zhu Tiezhi writing in Southern Weekly back in 2004, in the long wake of the SARS crisis. Even as the essay deals with public issues, its tone is personal:

On the first day of the new year, as I turned through the ink-fragrant pages of Southern Weekly, the first thing I saw, which was also the thing I most wanted to read, was the exclusive interview with Doctor Zhong Nanshan (钟南山). What moved me most were not Doctor Zhong’s views on SARS per se, things with which we are all long since familiar — rather, it was his thoughts on the attitude that should be taken in dealing with epidemics. Doctor Zhong believes: In cases where dangerous diseases suddenly break out, there must be no exaggeration, certainly no concealment, and the more you can talk honestly and clearly about the ins and outs with the public and with the World Health Organisation, and about how to achieve prevention, the more the public will be at ease. It is not as certain people would have us believe: that the more transparency there is, the more chaotic society will be.

Zhu’s concluding remarks are hopeful, with just a note of admonishment:

The new year has begun. In their attitude toward dealing with various sudden-breaking incidents, our Party and our government are facing the world, the public and public opinion with a much more liberal, open and responsible attitude. Well then, shouldn’t our government officials at various level also fully advance with the times on these questions?

And here, finally, is an excerpt from Zhu Tiezhi’s essay “If I Should Die,” included in his 2012 collection, Diving Into the Human Sea (沉入人海).

If I must die of cancer, I implore the leaders of my work unit and my colleagues not to press on with hopeless treatments. Because I know there are certain cancers that, although called cancer, are called such because modern medicine is at present helpless to deal with them. So-called humanitarian treatments are essentially about perpetuating our physical lives — and that is tantamount to the perpetuation of suffering. I know that my name means “iron will,” but in fact my will is weak, and I don’t believe I could withstand the suffering cancer would bring. I don’t wish my life to be a struggle, and in the end to lose all of my dignity, bed-ridden with a tenacious illness, my body pricked with tubes. Nor do I wish my family members to suffer as I am caught between the impossibility of life and death.