On August 22, as China marked the 115th birthday of Deng Xiaoping, the paramount leader who led China into the reform era, flowers were laid at the feet of a bronze statue of Deng in his hometown of Guang’an in Sichuan province. In some media, the birthday was an occasion to revisit Deng’s ideas and writings.

But a discussion soon bloomed across social media that the authorities found unacceptable, and a hasty wave of deletions across WeChat, Weibo and other platforms ensued.

At issue was a post made to “People’s Reading” (人民阅读) and “People’s Daily Press” (人民日报出版社), both official WeChat public accounts operated by the People’s Daily, the flagship newspaper of the Chinese Communist Party. That post, called “Deng Xiaoping Abolishes the Lifelong Tenure System for Leaders” (邓小平废除领导职务终身制), dealt with the now very sensitive issue of term limits for national leaders.

Sensitive why? Because while Deng Xiaoping, still greatly respected as a reformer, had made it a priority to ensure that national leaders did not serve indefinitely and run the risk of over-concentrating power in their hands and sapping vitality from the system, Xi Jinping oversaw the removal of constitutional term limits in March 2018, which some within China regard as a dangerous slide back into the painful past.

It was Deng who led China into the period of reform following the end of the Cultural Revolution, and a crucial aspect of the country’s transformation was a reassessment of the decades under Mao Zedong, during which Mao’s unbridled power had been a fundamental contributor to political, social and economic chaos. Limits on terms for national leaders ultimately came in the 1982 Constitution, which stipulated “no more than two consecutive terms” (连续任职不得超过两届) for key positions, including the national chairman (国家主席), often referred to misleadingly as the “president,” the deputy chairman, and the premier.

These constitutional changes followed the June 1981 “Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of our Party Since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China,” which included a rather frank (by the Party’s own standards) official assessment of the tragedies of the Anti-Rightist Movement and the Cultural Revolution. Noting that the failure to “institutionalize and legalize inner-Party democracy and democracy in the political and social life of the country,” had led to over-concentration of power and led to “the development of arbitrary individual rule and the personality cult in the Party,” the Resolution pledged to move the country in the direction of greater limitations on individual leadership:

The Party has decided to put an end to the virtually lifelong tenure of leading cadres, change the over-concentration of power and, on the basis of revolutionization, gradually reduce the average age of the leading cadres at all levels and raise their level of education and professional competence, and has initiated this process.

Reform of the political system was a key priority for China in the 1980s, and into the 1990s. The smooth handover of power to from Jiang Zemin to Hu Jintao in November 2002, and again to Xi Jinping in 2012, was regarded as a proof that the system of leadership succession and of collective leadership were being institutionalized, making real the limits on personal power that Deng Xiaoping had envisioned.

But in the less than seven years since Xi Jinping came to power, all of this progress seems to have unravelled. There is chatter enough in the halls to suggest that Xi’s dismantling of term limits in March 2018, through a constitutional amendment that was introduced without sufficient (or any) debate in the wake of the 19th National Congress of the CCP, has angered some with the Party, who are concerned that Xi now has too much power.

And of course, there have been plenty of signs that Xi has a tendency toward self-obsession and self-aggrandizement, that he envisions himself as a leader after the mold of Mao Zedong. For an illuminating, and amusing, look at this aspect of Xi’s personality, please revisit Qian Gang’s analysis of Xi Jinping’s signature.

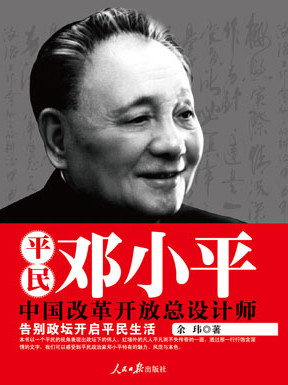

The posts made to the “People’s Reading” and “People’s Daily Publishing House” WeChat accounts on August 22, were in fact passages from a book about Deng Xiaoping published by the People’s Daily Publishing House in March 2013. The book, authored by former journalist Xu Wei (余玮), is called Deng Xiaoping: Ordinary Man.

The first chapter of the book is called “Retiring and Beginning a Normal Life,” and it includes the section shared by the above-mentioned WeChat accounts. While WeChat and other social media posts sharing the chapter under the title “Deng Xiaoping Abolishing the Lifelong Tenure System for Leaders” have been removed from the internet, and related comments are being actively scrubbed, the chapter can still be found online at a site dedicated to the book.

This most recent takedown of Deng Xiaoping, severely restricting discussion online around ideas and policies that are otherwise well-known, and historical accounts that have been printed and distributed by one of the Chinese Communist Party’s own publishing houses, is a further sign of just how far Xi Jinping has gone in pushing China back into the past.