In recent days China Central Television has hurled a series of verbal attacks at US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and others in the United States. As the US and China lock horns over the question of responsibility for the global coronavirus epidemic, the state-run network’s “International Commentary” (国际锐评) segment, which is featured on the nightly official news program “Xinwen Lianbo,” has been ruthless in its tone, and the attacks have sometimes been painful to read:

May 4: “The crazy-talking anti-China pioneer Bannon fears the world will not be chaotic“

May 1: “Aiming to threaten the WTO, Pompeo is making provocations around the world”

April 29: “Bearing the ‘four sins,” Pompeo has broken through the bottom line of being human”

April 28: “Pompeo, spreading ‘political disease,’ is turning himself into the public enemy of mankind“

In this war of words, one word in particular should grab our attention — “public enemy,” or gongdi (公敌). “International Commentary” has labelled Pompeo “the public enemy of mankind.”

What exactly does this mean in the Chinese context? In the eyes of the Chinese Communist Party, what sort of people or things merit designation as common enemies?

Looking back into PRC history, we can find a string such “public enemies,” from the Kuomingtang leader Chiang Kai-shek to Hu Feng, the writer who dared to criticize Mao Zedong’s views on art and literature. From American imperialism to the Falun Gong and more recently the novel coronavirus.

Chiang Kai-shek: Public Enemy

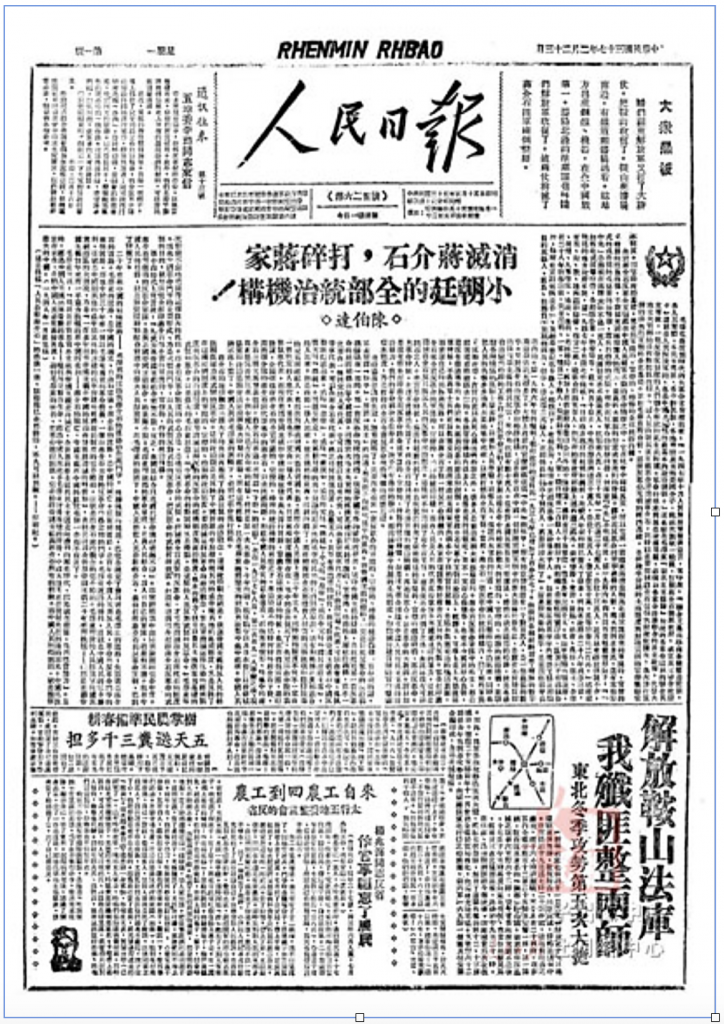

On February 23, 1948, the People’s Daily published on its front page a dispatch from Chen Boda, a close associate of Mao Zedong’s, called “Annihilate Chiang Kai-shek and destroy the ruling institutions of the Jiang family court!” Two small editor’s notes were added at the end of the piece. The first noted that the piece had been written in January of 1948, while the second noted that it was the last chapter in a book to be called “Public Enemy: Chiang Kai-shek.” The note indicated that the book had already been written, edited and typeset, and its publication was imminent.

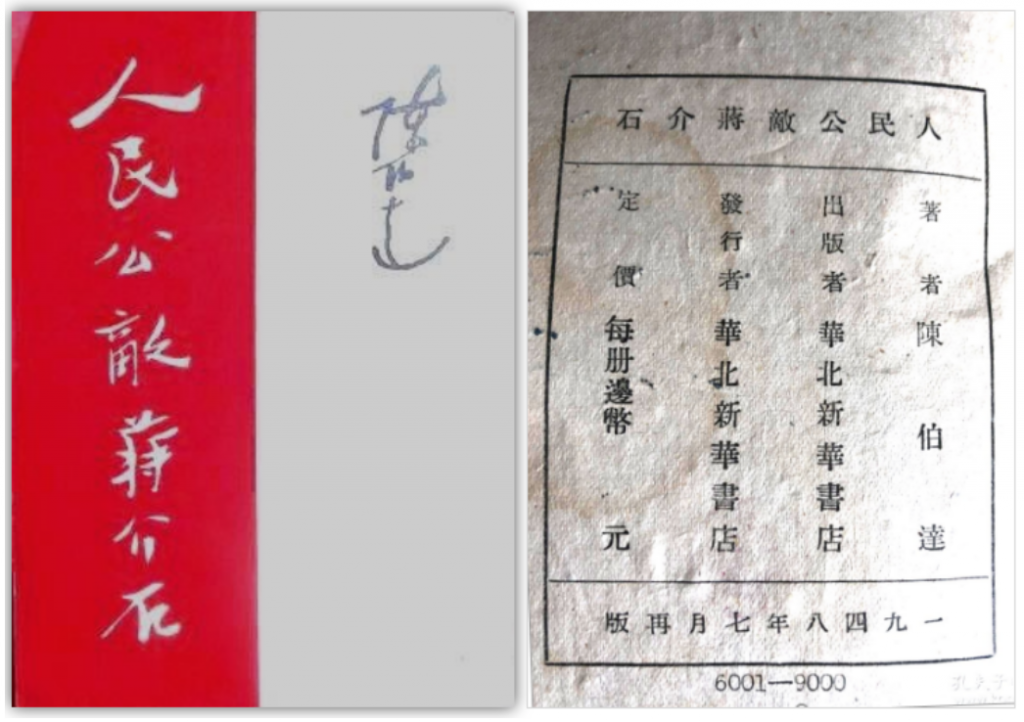

Five months later, in July 1948, Chen Boda’s book finally appeared, with just under 10,000 copies printed.

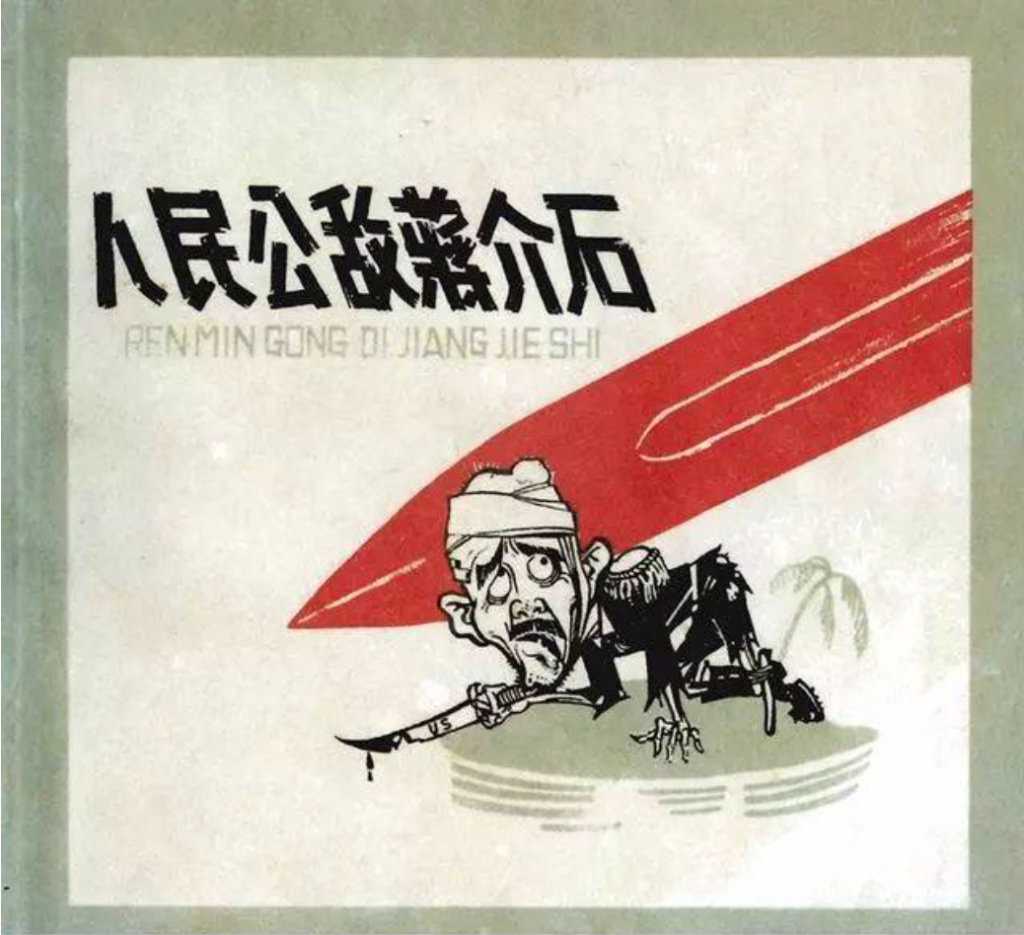

There was a documentary film to accompany the publication of Public Enemy: Chiang Kai-shek, and there were also comic strips and other adaptations. The label “public enemy” stuck with the KMT leader. In 1962, a cartoon of Chiang appeared on the cover of a graphic magazine published by the Liaoning Fine Arts Publishing House. Chiang was depicted as abandoned on the island of Taiwan as viewed from the coast of Fujian. The bloody dagger in Jiang’s hand bore the initials “US.” Across the top were the words: “Public Enemy: Chiang Kai-shek.”

Also in 1962, a film called “Public Enemy: Chiang Kai-shek,” produced by the state-run August First Film Studio, was screened in Beijing. The following year the film won “best documentary” at the “Hundred Flowers Awards.”

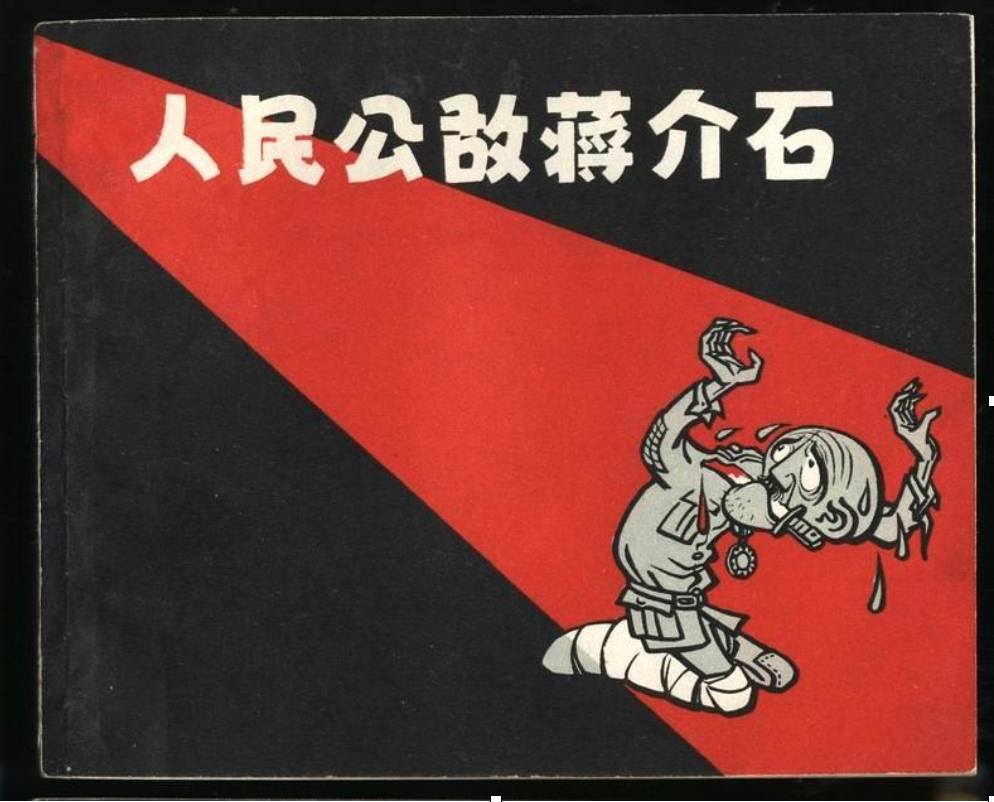

In July 1963, the Zhejiang Arts Publishing House published yet another collection of comics, this time by artists Zheng Wenzhong (郑文中) and Liu Yongfei (刘庸非). Chiang was depicted in a position of abject surrender, a dagger held in his teeth. The title: “Public Enemy: Chiang Kai-shek.”

American Imperialism and Soviet Socialist Imperialism

Under the foreign policy principle of “striking with two fists” (两个拳头打人) from the end of the 1950s and through the 1960s, both the United States and the Soviet Union were targets of Chinese ire, and both labelled as “public enemies of mankind” (人类公敌).

On July 25, 1958, the People’s Daily ran a piece called “The American imperialists are common enemies of the people of the world.” The rest of the headline alleged that newspapers in Jakarta had exposed American acts of sabotage in Indonesia happening even as “the United States set fire to the Middle East.” A piece in the newspaper the next month called the United States the “public enemy of the people of the Latin America,” while another about Thailand insisted that is was the “public enemy of the people of Asia.” Such headlines were not at all uncommon.

Meanwhile, though a bit later to the game, the Soviet Union came to share China’s rage with the United States. In March 1969, as a border conflict brought China and the Soviet Union to the brink of war, a wave of propaganda was unleashed against “Soviet revisionism.” On March 7 a report from the official Xinhua News Agency read: “The Soviet revisionists have bowed to the West German ruling clique to please US imperialism, have given way to the provocation of West German militarism, and have openly allowed West Germany to elect the West German president in West Berlin. The German people recognize that Soviet revisionism is the number one accomplice of the American imperialists, and is the public enemy of the German people and of the people of the world.”

Hu Feng and the “Gang of Four”

Public enemies were not just about foreign policy, but were also a way for the leadership to identify perceived internal threats. Both Hu Feng and the “Gang of Four” were labelled as “public enemies” in the midst of internal political campaigns. Articles criticizing Hu Feng as a “public enemy” appeared in the People’s Daily on May 26, 1955, and on June 12, 1969, under the headlines, “Hu Feng is the public enemy of the people,” and “Resolutely crushing the enemies of the people: the Hu Feng counterrevolutionary clique.”

As the Gang of Four were subdued in late October 1976, they were quickly labeled public enemies. On October 30, 1975, the People’s Daily published a front-page article decrying the crimes of the Gang, in which it said:

The “Gang of Four” are a group of bourgeois conspirators mixed in with the Party, bourgeois elements who suck the blood of the workers and poor peasants; walking capitalists who refuse to repent, they are public enemies of all the people of the nation.

Li Hongzhi and the Falun Gong

In emergence of the Falun Gang sect in China in 1999 presented the Chinese Communist Party leadership with another internal challenge. The group was outlawed in China in July 1999.

On February 2, 2001, the People’s Daily ran a front-page report called “The condemnation of the awakened,” which quoted a former (read, reformed) Falun Gong practitioner as saying: “When I saw reports yesterday about several deluded Falun Gong practitioners who blindly follow the cult of Li Hongzhi setting fire to themselves, I felt pained and so angry! These self-immolations again demonstrate that the Falun Gong is a wicked cult, and that Li Hongzhi is the public enemy of all the people of the nation, a running dog being used by anti-Chinese forces!”

The label “public enemy” was used frequently in reference to the Falun Gong. A People’s Daily article on July 10, 2002, for example, bore the headline: “The ‘Falun Gong’ is the public enemy of human society.”

The above examples from Chinese Communist Party history are just some of the more obvious illustrations of how the term “public enemy” has had a central role in the projection of the Party’s fears, of external threats and internal contagion. At its root, the notion of the “public enemy” is about the people and things China’s leaders imagine to pose an existential threat to the regime.

For much of this year, the coronavirus has been public enemy number one in China, and leaders have hoped to focus anger and attention on the virus itself in order to deflect global criticism. Back in early March, after Fox News anchor Jesse Watters suggested China should be asked to apologize for its role in the spread of Covid-19, foreign ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian struck back, his first point emphasizing that facing the virus was an urgent struggle for whch all should be responsible: “First, the epidemic is the public enemy of mankind, and the people of all nations are victims. I don’t know where this idea of apologies even comes from?” Later that month, as the People’s Daily criticized Pompeo for calling Covid-19 the “Wuhan virus,” it again emphasized the human nature of the threat: “Diseases have no borders,” the paper said, “but are the public enemy of mankind, and for these American politicians to go against the most basic international consensus, if this is not just ignorance it is done with ulterior motives.”

As the war of words with the United States grows louder, the “public enemy” spotlight seems to have turned from the virus to Pompeo. The language is poisonous and personal, recalling the heat of attacks made against the public enemies of China’s past. Pompeo is “wicked Pompeo” (邪恶蓬佩奥). His remarks point to a “nervous disorder” (神经错乱). He “carries four sins on his shoulders” (背负四宗罪). He has “broken through the bottom line of being human” (突破做人底线).

Such direct attacks on a senior US official are very rare indeed — and a sign of just how seriously relations have deteriorated.