Propaganda poster depicting Mao Zedong as the “helmsman.” Image from Wellesley University.

In the bulletin emerging last week from the Fifth Plenum of the 19th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Xi Jinping was praised as the “pilot at the helm,” or lǐngháng zhǎngduò (领航掌舵), a reference with strong echoes of China’s Maoist past. The relevant text in the bulletin read:

“With Comrade Xi Jinping as the core of the Central Committee of the CCP, and the pilot at the helm at the core, with the whole Party and full unity of people of all ethnic groups in the country, tenaciously struggling, we will surely be able to overcome the various difficulties and obstacles that appear on the road forward, and we will surely be able to energetically advance the forward progress of socialism with Chinese characteristics in the new era.”

The invocation of Mao-like status, even if oblique, was unmistakable, and it was noted in coverage outside China. In recent days, the “pilot at the helm” phrase has popped up repeatedly in the official media and on official government websites.

Among his several laudatory sobriquets, Mao Zedong was referred to as the “great helmsman,” or wěidà de duòshǒu (伟大的舵手). But Mao Zedong was not in fact the first leader in China to be honored in this way, with terms like “helm master” (舵师) or “helmsman” (舵手).

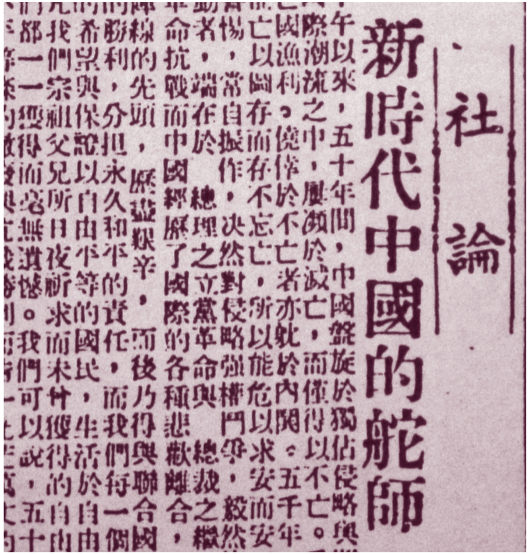

The image below is an official commentary from the May 18, 1945, edition of the Central Daily News, the flagship propaganda organ of the Kuomintang, or the Nationalist Party of China. The headline reads: “The Helms Master of China’s New Era” (新时代中国的舵师). This refers, naturally, not to Xi Jinping – the helmsman of China’s 21st century “new era” – but rather to Chiang Kai-shek (蒋介石), the Republic of China’s top leader, and Mao’s bitterest enemy.

The term used here for Chiang Kai-shek is “helms master,” or duoshi (舵师). But the nearly identical honorific “helmsman,” or duoshou (舵手), so closely associated now with Mao Zedong, was also used for Chiang.

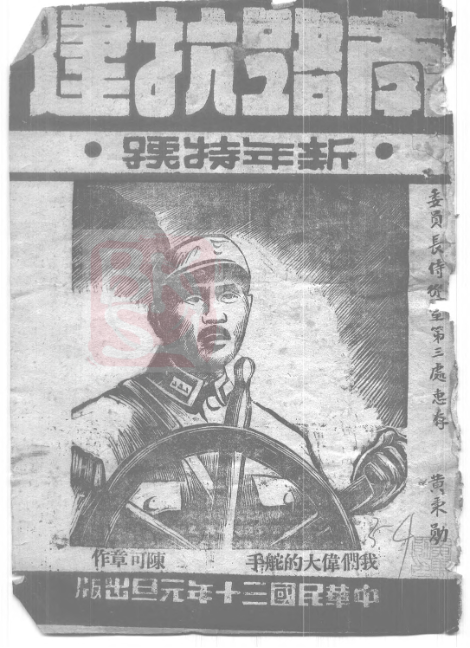

The image below is from a magazine cover in 1941, the same year the Allies declared war on Japan. The text directly below the illustration, which shows Chiang literally at the helm of a ship (something rarely seen), reads: “Our Great Helmsman” (我们伟大的舵手). The language here, as we can note from the propaganda image from the Cultural Revolution further above, is already identical to that eventually used for Mao.

In the late 1940s, as the Chinese Communist Party emerged victorious over the forces of the Kuomintang, there was a popular song praising the CCP that was called, “You Are The Beacon” (你是灯塔). The lyrics went: “You are the beacon, shining on the ocean before dawn. You are the helmsman, piloting us forward.” These words, which of course refer to Mao Zedong, are some of the earliest to use helmsman in reference to China’s revolutionary leader.

But Mao was not in fact the only helmsman at that time. If we search the archives of the People’s Daily, which was launched in 1946, we find that “helmsman” appeared quite early. Lenin was referred to as the helmsman. Stalin too was the helmsman. And Mao was the helmsman. In all instances they were referred to as the duoshou (舵手).

On the eve of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, we can find reference to Mao as both the “great leader” (伟大的领袖) and the “helmsman,” as in one article appearing in the People’s Daily on September 26, 1949: “Great leader, guide, and helmsman, Comrade Mao Zedong! When we say your name, we feel glory and pride, and we find courage and strength.”

Just days later, however, the honorific “helmsman” is used in the paper to refer not just to Mao but to the Party’s senior leadership group. The news item, dispatched from Nanjing by Xinhua News Agency, read: “Nanjing, once the center of the Kuomintang’s reactionary rule, rejoiced last night and unanimously supported the helmsmen of the people – the elected Mao Zedong, chairman of the Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China, Vice-Chairman Zhu De, Liu Shaoqi, Song Qingling, Li Jishen, Zhang Lan, and Gao Gang.”

Several months later, on February 21, 1950, the People’s Daily published a verse by the poet Tian Jian (田间) that praised both Stalin and Mao. Written in a time of deep friendship between the CCP and the Soviet Union, the poem was called: “Two Good Helmsmen, in the Same Boat” (两位好舵手,同御一条船).

By the beginning of 1956, the Sino-Soviet friendship had turned cold, as Mao bitterly opposed the de-Stalinization of the USSR. At the 8th National Congress of the CCP, held in September that year, Liu Shaoqi praised Mao Zedong, saying that he had “served an important role as the great helmsman in our revolutionary cause.”

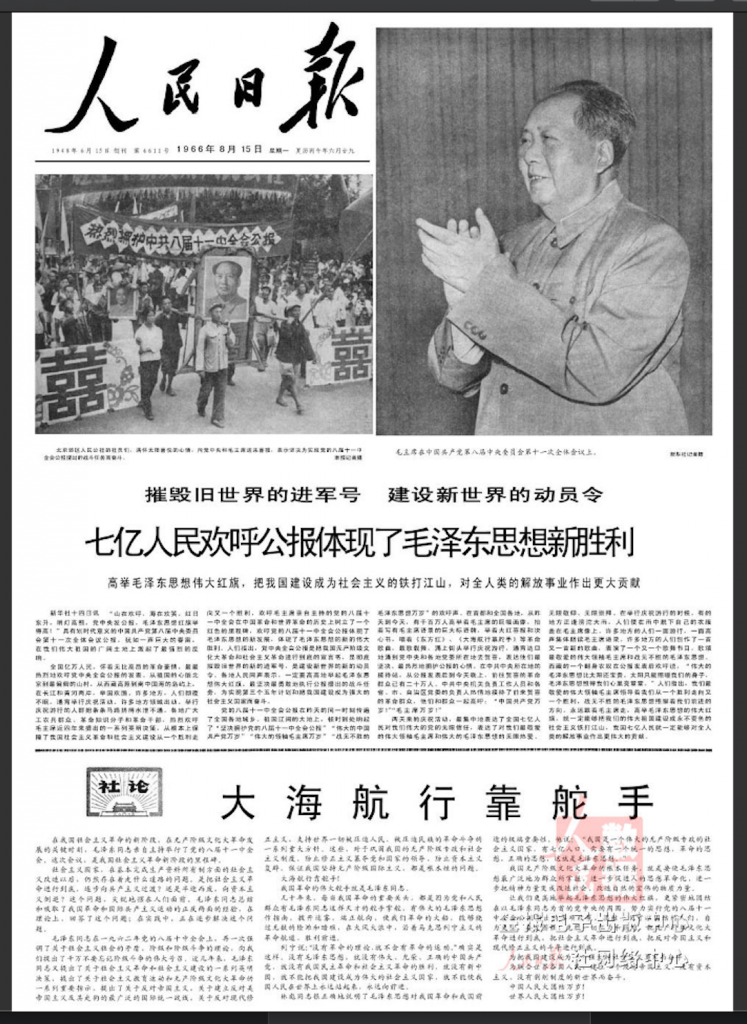

Ten years later, at the outset of the Cultural Revolution, the term “great helmsman” became inseparable from the figure of Mao Zedong, beginning with the Eleventh Plenum of the 8th Central Committee. It was at this meeting that Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping were sidelined, criticized as the “bourgeois headquarters” within the Central Committee. The Cultural Revolution from this point went into full swing, accompanied by the revolutionary song, ““Sailing the Seas Depends on the Helmsman” (大海航行靠舵手), written by Wang Shuangyin in 1964.

Below is the front page of the August 15, 1966, edition of the People’s Daily. The lead commentary under the image of Mao Zedong bears the title of Wang Shuangyin’s anthem: “Sailing the Seas Depends on the Helmsman.”

“Great helmsman” became one of the “Four Greats,” the standard set of honorifics for Chairman Mao: “Great Guide, Great Leader, Great Commander, Great Helmsman.”

For many, many years after Mao Zedong’s death in September 1976, no Chinese leader claimed the helmsman honorific for himself. In fact, there was just one instance of the word’s use for a senior leader, and this came after Deng Xiaoping’s death in February 1997. A report about Deng’s sea burial mentioned that in “the Spring of 1992, Deng Xiaoping again came to the seaside, and like a helmsman, again pointed the direction of the voyage for China’s reform and opening and modernization.”

Jiang Zemin never sought the honorific for himself. Nor did Hu Jintao. Both governed in times of growing collective leadership, during which “the legitimacy of the general secretary has progressively become based more on rational authority than charismatic authority.”

The equations have changed in Xi Jinping’s “new era.” In November 2016, at the Sixth Plenum of the 18th Central Committee, Xi was first honored as the “core” (核心) of the CCP. In January of the next year, months ahead of the formal removal of presidential term limits at the NPC, the People’s Daily ran a piece called, “The Choice of History, the Expectations of the People: Comments on National Governance with Comrade Xi Jinping as the Core Since the 18th National Congress of the CCP.” The article included this passage: “In moving forward toward our dream, the first priority is the helm; to overcome difficulties, we need more leadership.” And this one: “This leader, which America’s Time magazine called ‘the central figure in China’s new round of transformation,’ is like a helmsman who has resolutely declared it is ‘time for reform,’ and is leading this reform in every detail.”

It was from this point, we can say, that Xi Jinping became China’s new “helms master” (舵师), “helmsman” (舵手) and “pilot at the helm” (掌舵人).