In December, Xi Jinping formally declared victory in his push to eradicate poverty in China. Resorting to a phrase commonly at the heart of China’s external propaganda on poverty, state media claimed that 100 million people in the country had been “lifted out of poverty” since 2013. A momentous achievement, surely.

But like any momentous achievement in which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has invested its legitimacy and standing, this victory was always in the cards. It was never a matter of ensuring the right outlay of resources, or that resolute government officials had the right set of strategies. From the moment Xi Jinping pledged to eradicate poverty in 2015, the story had been written. It needed only elaboration – through a vast national network of county and city propaganda offices, and through the dogged work of a media system whose allegiance had already been pledged.

This is not to say that China’s anti-poverty work has been nothing but empty propaganda. Nationwide efforts at “poverty alleviation,” or fupin (扶贫), have quite possibly had a real impact on the lives of many. They can, if one so chooses, be viewed through the lens of social and economic policy. But to ignore the role of China’s vast media and propaganda system, single-mindedly trained on the direction of public opinion both inside and outside the country, is to ignore one of this story’s central threads.

Gearing Up for Victory

As 2019 came to a close, it was already plain that the achievement in 2020 of a “moderately prosperous society” and a decisive victory over poverty would be the central propaganda theme for the coming year. The phrase “targeted poverty alleviation” (精准扶贫), which Xi had introduced in 2013, was everywhere, a buzzword even in the real estate sector.

As the CCP readied itself to close the book on the 13th Five-Year Plan and inaugurate the next economic era with fanfare, Party-state media stacked their editorial plans with touching retrospectives and intimate portraits of rural lives that had been transformed by the compassionate hand of the Party.

Even as the epidemic raged in Wuhan in January, as yet not publicly acknowledged as a serious national crisis, the fight against poverty was the story of the year, and Xi Jinping was its main protagonist. The Party’s flagship People’s Daily set the tone with a series called “The General Secretary Visited Our Home,” featured repeatedly on the paper’s front page, but also disseminated widely, through app-ready content, in numerous state media outlets.

The app-based content featured brushed-up images like the one below, echoing propaganda images of Mao from a bygone era. Xi Jinping, hand-in-hand with the people, in touch with their immediate concerns.

The epidemic in Wuhan eventually upended the publicity objectives of propaganda officials, at least for a time. But by April and May 2020, the focus had been drawn back to poverty and the achievement of a “moderately prosperous society.” The demand for anti-poverty coverage necessitated a wealth of local stories from across rural China. Such stories were in ready supply. After all, the narrative push had always been closely intertwined with the mobilization of the campaign itself.

Local Myths in the Making

Enter the story of Dong Heqin (董贺勤), a once impoverished farmer from Anhui province who in recent years, aided by the grace and wisdom of anti-poverty officials, managed to dramatically turn his fortunes around.

According to the basic thread of Dong’s story, he was officially designated as living in poverty in 2014, after spending all of his life savings for the treatment of his sick son. In 2015, directed by local officials charged with anti-poverty work, Dong began planting chili peppers on his land. He now earns more than 600,000 yuan, or around 93,000 dollars, from his crop annually.

Conduct an image search for Dong’s name and you are treated to a mosaic of anti-poverty propaganda. Dong working among his rows of peppers. Dong among the honorees in a 2018 ceremony for “positive role models,” bathed in blazing light onstage. Dong pictured during a television interview with the official Xinhua News Agency. Dong the “Moral Exemplar” (道德模范).

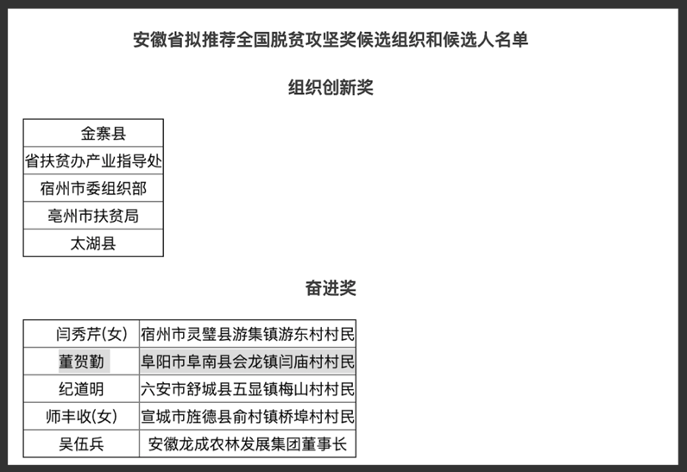

According to CMP’s database search, Dong Heqin did not emerge on the national media stage until July 2018, at which point he was hustled to center stage by Anhui propaganda officials eager to supply their own candidates for a national propaganda campaign on the “tough battle for poverty alleviation” (脱贫攻坚战), announced as a national priority at the Fifth Plenum of the 18th CCP Central Committee in October 2015. Responding to the campaign, the “National Poverty Alleviation Award” (全国脱贫攻坚奖) had been launched in September 2016 by the State Council’s Poverty Alleviation and Development Small Group.

In the years and months that followed the award’s creation, poverty relief officials across the country were on the hunt for inspirational examples, for seemingly ordinary country folk who could be plucked out from the masses and paraded through the news headlines. From 2017 onward, China’s government made an active push to foster the creation of “poverty alleviation and prosperity leaders” (脱贫致富带头人) in poor areas across the country, seen as critical to the overall poverty alleviation strategy, which itself included a section on “adhering to propaganda models.”

Later reports would make clear that Dong Heqin had been chosen in April 2017 as the designated “poverty alleviation and prosperity leader” for Anhui’s Funan County. And as award season approached for the “National Poverty Alleviation Award” in 2018, the Anhui Provincial Center for Poverty Alleviation Propaganda and Education released its list of candidates for the national stage on July 27. Dong Heqin was included on the roster of candidates for the “Endeavor Award” (奋进奖).

Shortly after, in August 2018, Fuyang Daily, the local Communist Party newspaper in Dong’s hometown, ran a profile of Dong Heqin as a “leader in throwing off poverty and becoming prosperous.” It told the story of how Dong had once made decent money off in Beijing, a migrant worker running his own recycling station. But the illness of his son in 2007 had placed Dong and his entire family in jeopardy. Finally, in 2015, after several trying years, Dong, who was now back in his native Yanmiao Village with medical debts for the treatment of his son piling up, had been designated a candidate for “targeted poverty alleviation.”

The next year, with government help, Dong worked toward expanding his chili farming operation, as the Fuyang Daily explained:

In 2016, 6,000 yuan in industrial poverty alleviation funds issued by the government came like welcome rain to Dong Heqin. “My planting technology had passed muster, and my peppers had been well received in the market. I want to expand scale, but I had no capital.” After receiving the government’s industrial poverty alleviation funds, Dong said, he built a new steel greenhouse and expanded his scale. In 2017, his income from growing peppers reached 230,000 yuan. Not only did he throw off poverty, but he also paid his lingering debts, and his life was full of sunshine.

Perfectly on cue for a set piece on the grace of the Chinese Communist Party, the Fuyang Daily profile ended with Dong’s conversion. He had joined the Party in the hope that he might “better play the role of a model leader in poverty alleviation.” “I sincerely thank the Party’s poverty alleviation policy for making a big change in my life,” the paper quoted him as saying.

In January 2019, the city of Fuyang looked back on 2018 to showcase exemplary instances of “positive energy” – a reference to Xi Jinping’s injunction for the media and society to avoid negative reporting and seek examples of inspiration and unity. The retrospective included Dong Heqin as a “model person escaping poverty” (脱贫人物典型). “In the past, debts forced him to leave home and seek a living,” the short post read. “But now, relying on the Party’s poverty alleviation policies, he has thrown off poverty through struggle and become prosperous.”

The same month, a special feature on Dong carried on the province’s official government news website, Anhui News (中安在线), continued the account of his trials and tribulations, and the dramatic turnaround made possible by poverty alleviation funds.

By the end of 2019, as China was gearing up for the 2020 campaign toward the “victory” over poverty, local stories of success were regular fodder on national news platforms. On December 31, several weeks after Xi declared a decisive victory over poverty, The Paper, a Shanghai-based news website under the state-run Shanghai United Media Group (SUMG), ran a special story on the theme, “Targeted Poverty Alleviation In Step with a Moderately Prosperous Society” (精准扶贫同步小康). The subject was again Dong Heqin, the chili pepper farmer from Anhui.

This version of Dong’s story, which ran in scores of outlets in December 2019 and January 2020, was sourced to China Poverty Relief magazine (中国扶贫), a news outlet operated by the State Council’s Poverty Alleviation and Development Small Group, the same office that had established the “National Poverty Alleviation Award” in September 2016.

By this point, Dong’s story had come full circle. A national movement coordinated from the top had generated demand across the country for exemplary cases. These had trickled back up to the top as local leaders signaled their compliance, offering up lists of local award candidates, like ritual offerings of “positive energy.” Repackaged at the national level, stories like that of Dong Heqin were delivered through outlets like The Paper, Xinhua and the People’s Daily.

Satellites of Propaganda

When they conform so perfectly to the CCP’s master narrative on poverty eradication, how far can we trust stories like that of Dong Heqin? They show at times such an eagerness for perfection – the tears trickling before the hallelujah moment when the protagonist thanks the Party and then the government, always in that order – that they resemble, in their DNA, the conscientiously crafted falsehoods of China’s past.

This is the ghost of basic skepticism that haunts all of the grand claims in China’s tightly controlled press. When success is the only outcome possible, when happy endings are the order of the day, can success and positivity be trusted at all?

There is a slang term in Chinese today that speaks to this basic skepticism, directing suspicion at those boasts that are so enlarged that their seams begin to tear, revealing the stuffing inside. That term is “launching a satellite,” or fangweixing (放卫星), and its history stretches back to the calamitous political actions of the 1950s, when tens of millions starved in the wake of such lies.

When the Soviet Union launched Sputnik I, the world’s first artificial Earth satellite, on October 4, 1957, the event spawned a frantic response from the United States, demonstrating Soviet advancements in technology in the midst of the Cold War. In November 1957, shortly after the successful launch of a second Soviet satellite, communist leaders from around the world gathered in Moscow for the 40th anniversary of the October Revolution, where Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev pledged to surpass the US in industrial output within 15 years.

Enchanted by Khrushchev’s ambition, Mao Zedong followed with his own declaration that China would achieve industrial glories all its own, surpassing Great Britain in steel production within 15 years. The next year, grain and steel production were the pillars of Mao’s economic plan, and communities across China labored blindly under impossible quotas. As the political incentives for falsehood climbed, so the claims became ever more unbelievable. Propaganda across the country likened the ambition for high production to the success of Sputnik, talking metaphorically of “satellites” of productivity.

On October 26, 1958, an entire page in the People’s Daily spoke of economic miracles in China’s northwestern Qinghai province. Everything was “astonishing” (惊). The treasures in the province’s underground mines were “so rich as to astonish people.” Grain production was so abundant that it “crossed the Yellow River.” The page even included a poem called “Satellites of Wheat Astonish the World” (小麦卫星惊世界), the first of four stanzas reading:

Satellites of wheat have launched in Qinghai,

Eight thousand per mu, the yields astonish the world.

Over the miles, clashes of thunder and flashes of lightning,

Mean that fortunate news is nigh!

小麦卫星出青海,

亩产八千惊世界,

千里的雷声万里的闪,

带着喜讯传开来.

These days, the CCP no longer talks in its official discourse about “sending up satellites” of economic or other policy glory. But the phrase remains as a popular reference to absurd and boastful acts of propaganda. And last week, a post on China’s WeChat platform applied the phrase to Dong Heqin’s story. The headline: “Officialdom Launches a Satellite: It is Captured Alive by Netizens!” (官方放卫星,被网友活捉).

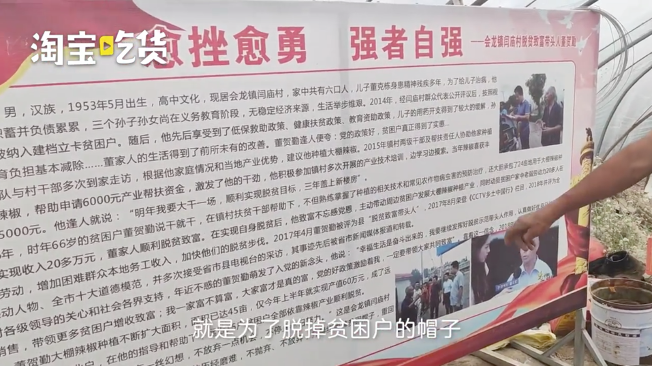

The WeChat article was based on a video of that appeared online in May 2020, after the immediate crisis of the Covid-19 epidemic had been contained in China. It begins as a reporter enters one of Dong’s greenhouses and walks toward the farmer, who rises from a chair next to a full-sized propaganda billboard. In what any novice would recognize as a scripted action, Dong never lifts his eyes from the official Party journal he is obligingly pretending to read. On the magazine rack behind him hang copies of official newspapers, including the flagship People’s Daily.

Cut to Dong laboring away among his rows of peppers as he again tells his rural-rags-to-rural-riches story. “Why do I do this work when I’m so old?” the 68 year-old Dong asks the reporter. Pointing to the propaganda billboard, an official account of his success, he answers with a phrase nearly ubiquitous in official media coverage of poverty alleviation efforts. “It’s because I wanted to take off the hat of poverty.”

The obvious creative liberties of the video aside, the WeChat article points out a number of serious questions looming behind Dong’s simple turn-around story.

Dong has claimed that he now earns 640,000 yuan, or about 100,000 dollars, farming chili peppers on 50 mu of land, this being just over 33,000 square meters. Farmers on average in China have access to just 1.3 mu of land, and for many farmers in Anhui that number is even lower, just one mu, or around 666 square meters.

So the first question is how Dong managed to get roughly 50 times the land available to other farmers in the area? Was this land transferred to him? Who came up with this money? If the land was sold, where are the farmers who sold it? Have they too “taken off the hat of poverty”? This is quite a serious and sensitive question in a country where farmland is scarce and often fiercely contested.

“Remember, Uncle Dong had an established file and card as an impoverished family, and land transfers do not come cheap,” the WeChat article cautions.

But let’s assume the transfer did happen. The WeChat article estimates that the cost of building greenhouse structures on Dong’s 50 mu of land would be no less than 50,000 yuan per mu, which means the total cost would run to 2.5 million yuan, or nearly 390,000 dollars. “Good Lord,” the article gasps. “Who came up with that money?”

There are problems, too, with Dong Heqin’s claimed annual income of 640,000 yuan. Considering that 1,500 kilograms of peppers for each mu of land would be considered a high yield, and would earn around 5,000 yuan, Dong could expect, at the high end, an annual turnover of about 250,000 yuan. This is less than 40 percent of what Dong has claimed in report after report.

Has Dong used some of his newfound wealth to subscribe to every Party journal and paper he can get his hands on? And has he erected his own propaganda billboard? Well, we do know that Dong has been quoted in several stories as saying he joined the Communist Party because he hoped to become a better “model leader in poverty alleviation.” Perhaps, then, this is his personal library?

The WeChat article is less charitable, concluding that the propaganda billboard and magazine rack would most definitely have been lugged over from the local government office. It is all just too much, after all. Too perfect. The seams are coming apart, the stuffing exposed.

The article closes by bemoaning the fact that media in China continue to produce such “standard rubbish” (正经的胡说八道) in the face of what is a major policy of the central government, something to be taken seriously. “What is most lamentable,” it concludes, “is that such rubbish is a absolutely everywhere!”