Today is the 24th World Press Freedom Day. First conceived three decades ago at a UNESCO conference in Namibia still regarded as having catalyzed global press freedom efforts, the day has been commemorated every year since 1998. In its concept note for this year’s conference, with the theme “Information as a Public Good,” UNESCO said that a key objective would be encouraging greater information literacy in order to “enable people to recognize and value, as well as defend and demand, journalism as a vital part of information as a public good.”

As it has for a quarter century, the UN event passed quietly today in China. There was no mention in mainland Chinese media of “World Press Freedom Day,” in either official Party-state media or in the country’s increasingly straightjacketed commercial press.

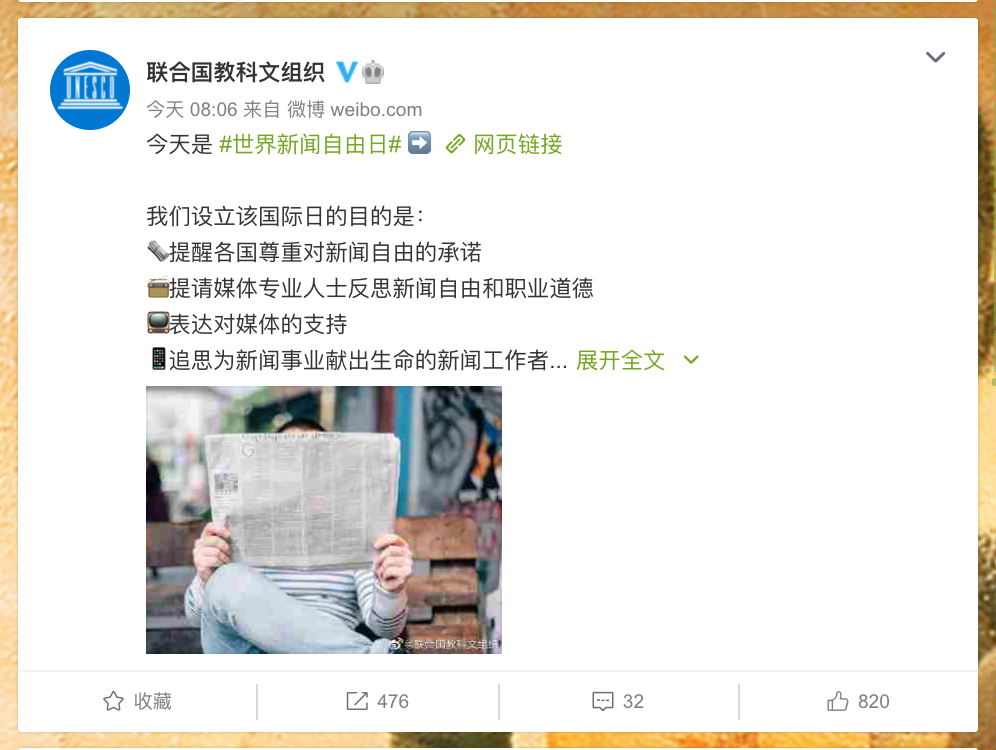

As for social media platforms, one rare mention appeared on UNESCO’s official Weibo account, which sought to explain the importance of commemorating the day:

Our reasons for establishing this international day are:

To remind countries to respect pledges for press freedom

To call on media professionals to consider press freedom and professional ethics

To express support for the media

To remember those journalists who had given their lives for journalism . . . .

Rather hopefully, the UNESCO account topped its post with the hashtag #WorldPressFreedomDay (#世界新闻自由日). Users clicking on the hashtag, however, were given an error message that read simply: “We’re sorry, there are no results for ‘World Press Freedom Day.’”

It cannot be true that there are “no results.” There is at least one other post from UNESCO alone using the hashtag. That post reads: “There are many questions that we don’t have the means to ask. If journalists are not free to ask questions, we will not know the answers.”

But the bottom line is that World Press Freedom Day is something about which Chinese are not free to ask. One user who had clearly attempted to learn more by clicking the tag wrote in a comment under the UNESCO post: “This TAG is already gone.” A search for World Press Freedom Day through Baidu, China’s top-ranking search engine, also turns up no current coverage or discussion of the issue.

Nor in recent days has there been any mention of “press freedom” or “World Press Freedom Day” from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, despite remarks from US Secretary of State Antony Blinken on April 28 at a roundtable to commemorate the international day, during which he talked about a “democratic vision for global information,” and singled out China as a source of concern for the US and its allies. “The real concern here is Beijing’s use of propaganda and disinformation overseas through state-owned media enterprises and platforms with the purpose, in part, of interfering or undermining democracy while restricting freedom of the press and speech in China,” Blinken said.

World Press Freedom Day is a no-go area in China, and near silence has attended the day since its inception. This is because the very concept of a press that operates independently in the public interest is politically unacceptable in China, where the Communist Party has long demanded that the media are subservient to itself as the arbiter of the public interest. The term “press freedom,” or xinwen ziyou (新闻自由), has been regarded as sensitive since the earliest years of the People’s Republic of China, and has often been attacked and dismissed as a bourgeois fancy of the West – or worse, as a tool wielded by a hypocritical West, led by the United States, to defile and slander China and the CCP.

“Press freedom” is rarely ever used in the Chinese media, where less ideologically charged phrases like “freedom of expression” (言论自由) are preferrable if references are necessary. Under Xi Jinping, the term “press freedom” has slipped from sensitive territory into the formally taboo zone. An internal communique released in 2013 by the CCP’s Central Office, which has since been known as “Document 9,” listed “the West’s idea of journalism” among seven restricted ideas. “Some people, under the pretext of espousing ‘freedom of the press,’” said the communique, “promote the West’s idea of journalism and undermine our country’s principle that the media should be infused with the spirit of the Party.”

“So-Called Press Freedom”

One of the most common contexts for the appearance of “press freedom” is the longer phrase “so-called press freedom” (所谓的新闻自由). In the wake of the crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrators on June 4, 1989, the People’s Daily reported that Xu Zhen (徐震), the head of the journalism school at Shanghai’s Fudan University, advocated deeper “political education” for journalists.

During the unrest, he said, some people in society had raised up so-called “freedom of the press” and the students had followed suit, marching on the streets with banners saying “freedom of the press, give me back my [Word Economic] Herald.” In fact, these students did not know what freedom of the press meant. In a class society, there is no freedom of the press beyond class. Some people advocate “freedom of the press,” but does this mean they have the freedom to oppose the major decisions of the Party’s Central Committee and to incite the overthrow of the legitimate government?

In 2005, a commentary in the paper took aim at what it characterized as the corrupt “basic nature” of “the West’s press freedom.”

For a long time, there have been certain people who do not understand the true meaning of freedom of the press, or because they do not know enough about the world and the reality of journalism today, they bear misconceptions in their minds. Essentially, there are two main aspects: First, they blindly worship the West’s press freedom, thinking the West is the paradise of press freedom; second, they think press freedom means reporting whatever they want to report, reporting however they want to report, and being completely free from restrictions. In order to clarify the true meaning of press freedom and bring into play the rational guidance of press freedom, it is necessary to revisit this issue.

The commentary, echoing attacks going back to the 1950s, argued at length that press freedom in the US was a figment, that speech was severely restricted by capital on the one hand and political interests on the other. Noting the mid-air collision of a US Navy intelligence aircraft and a Chinese fighter jet over the South China Sea in April 2001, the commentary said: “This is so-called ‘freedom of the press,’ a freedom that distorts the truth and puts lives and human rights at risk.”

Revealing the CCP’s view of “press freedom” as being defined ultimately by the Party’s own interests and its ostensible representation of the people’s interests, the commentary then spoke of “correct guidance of public opinion” (正确的舆论导向) – the policy, implemented in the aftermath of June Fourth, that essentially avers that the Party must “guide” and control speech and the media in order to maintain political control:

China’s freedom of the press must be conducive to economic development, social stability and the improvement of people’s living standards, and journalists must adhere to the correct guidance of public opinion, promoting the main theme, so that the news media can provide a strong ideological guarantee and public opinion support in the great cause of building socialism with Chinese characteristics. This is also the essence of freedom of the press.

Such a bald-faced affirmation of the CCP’s media control policies couched in the language of “press freedom” is exceptionally rare. In the vast majority of cases, “press freedom” is treated as negative and oppositional, warranting only suspicion.

More recently, a report in the People’s Daily on September 12, 2019, addressing protests in Hong Kong, said that “black hands behind the scenes are the root of the Hong Kong riots, and Hong Kong’s so-called press freedom has reached a point of absurdity.” In March 2020, as China responded angrily to “discriminatory measures” against Chinese state media in the US – referring to the move by the Trump administration to designate such media as state operatives – the People’s Daily wrote that the measures had “exposed the naked double standard of America’s so-called press freedom.”

The phrase “press freedom day” is mentioned in the official People’s Daily newspaper just three times in its 75-year history, and only one of these mentions pertains to the UN’s international day.

The first two mentions, appearing in 1959, make reference to an event held in Cuba just months after Fidel Castro had been named the country’s prime minister, and weeks after he had instituted agrarian reforms that broke up landholdings. A report on June 9 read: “Prime Minister Castro told the press at a conference to mark Press Freedom Day on July 7 that Cuba ‘will not change a single comma’ of the agrarian reform law. Castro stressed that although the agrarian reform has caused opposition, ‘the enemy has spurred the revolution forward.’”

The third mention, the only in the People’s Daily to date to reference the UN event, came on May 5, 2009, following comments in Washington by both President Barack Obama and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to mark World Press Freedom Day. On May 1, Obama had noted “the indispensable role played by journalists in exposing abuses of power,” and he had urged greater attention to the plight of journalists across the world who “find themselves in frequent peril.” Among these, he named in particular Chinese journalist Shi Tao (师涛) and Chinese political activist Hu Jia (胡佳).

A May 5, 2009, article in the People’s Daily urged the United States to “respect the facts, take a correct view of China’s press freedom situation, respect China’s judicial sovereignty, and stop making careless remarks about China’s press freedom situation.” Chinese official media coverage following Obama’s criticism marked a high point for the appearance of “World Press Freedom Day” in China’s newspapers. But the coverage was uniform, with at least 37 papers and scores of websites all running a single release from the state-run China News Service that mirrored the People’s Daily article.

The most recent article in the People’s Daily to mention the term “press freedom” was a commentary on February 6, 2021, attributed to “Zhong Sheng” (钟声), a pen name used for important pieces on international affairs on which the leadership wishes to register its view. The commentary followed the decision by the UK’s Office of Communications (Ofcom), the government regulator for broadcasting and telecoms, to withdraw the UK broadcast license for China Global Television Network (CGTN), China’s state-run English-language satellite news channel. The “Zhong Sheng” article called the decision “a brutal suppression of Chinese media,” and said it had “fully exposed the falseness of the so-called press freedom flaunted by the UK.”