THE CMP DICTIONARY

Ideological and Political Education

Ideological and Political Education

Students in wearing their red scarves in a Chinese school, showing they are members of the “Red Pioneers,” a mass youth organization that begins the political education process for China’s youngest children. Image from Wikimedia Commons available under CC license.

Training in ideology and correct political thinking have long been a part of the political culture of the CCP, stretching back into the 1940s, and drawing also on lessons from the Soviet Union. Reports in the People’s Daily in the mid-1940s spoke of the need to “firmly grasp ideological education” (抓紧思想教育), which could involve publicizing the violent acts committed by the enemy, Chiang Kai-shek, or even deterring peasants from classist infighting and trying to foster unity of purpose. After the founding of the PRC, as the education system was reformed, one priority became “implementing ideological and political education through the whole education process” (把思想政治教育贯彻在全部教育过程中).

In the aftermath of the crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrations in 1989, which precipitated a crisis of credibility for the Party, the CCP renewed its focus on “ideological and political education,” with the Ministry of Education and the Central Committee of Chinese Communist Youth League (共青团中央) working to enhance related education modules at all levels of the education system, from primary school to university. The coursework included subjects such as “The Basic Principles of Marxism,” “Introduction to Maoism and the Theoretical System of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics,” and so on.

Use of the shorthand sizheng was not common until the late 2000s, though there was continued discussion in the state media through the decade of the long-hand “ideological and political education,” particularly following the issuance in October 2004 by the CCP Central Committee and the State Council of Opinion on Further Strengthening and Improvement of Ideological and Political Education for College Students (关于进一步加强和改进大学生思想政治教育的意见). That document said that “strengthening and improving the ideological and political education of college students is an extremely urgent and important task,” and that “raising their ideological and political character” was necessary in order to “cultivate them into the builders and successors of the socialist cause with Chinese characteristics.”

There was a clear sense of urgency in discussions of the phrase about ensuring education in the basics of political obedience to the CCP – though it was never put quite so directly – and the need to “love the Party, love the mother country and love socialism.” But there was also anxiety about the fact that university courses in “ideological and political education” had become wooden, formulaic and detached from reality, “particularly in a period of social and economic transition.”

Political Education in the Xi Era

In many ways, “political education” can be said to be undergoing a renaissance in the Xi era. There is much more discussion, certainly, of the term itself. Of the nearly 766-odd mentions in the People’s Daily through its history of the abridged term sizheng (all coming after 1994), 700 come during the Xi era. There has been a steady emphasis on the need ensure obedience to the CCP within the university ranks, that the “Party’s banner flies high in the grassroots positions of colleges and universities.”

In a speech to a seminar for teachers of ideological and political theory courses in March 2019, Xi Jinping said sizheng courses are necessary in order to train generations of talents who support the leadership of the Communist Party of China. Xi said:

Young people are the future of the country and the hope of the nation. The most important thing in youth education is to teach them the right ideas and guide them to take the right path . . . . The role of sizheng education is irreplaceable, and the teachers have a great responsibility. The most fundamental thing is to fully implement the Party’s education policy, and the most important thing is to carry out Marxist theory education, use the new era of socialist ideas with Chinese characteristics to forge the soul and educate people, guiding students to build up the confidence about the path of socialism with Chinese characteristics (道路自信), confidence about the theories [of the Party] (理论自信), confidence about the institutions [of our system] (制度自信), and confidence in our culture (文化自信).

This speech was re-published in August 2020 as a featured article in the CCP’s leading theoretical journal, Seeking Truth, called “Political Education Courses Are the Key Course to Implementation of the Fundamental Task of Moral Education” (思政课是落实立德树人根本任务的关键课程).

This was not the first time that Xi Jinping spoke on the importance of sizheng. During the National Ideological and Political Education Conference (全国高校思想政治工作会议) in 2016, Xi emphasized that “our universities are universities under the leadership of the Party, and universities of socialism with Chinese characteristics.” Sizheng, therefore, was essential to the fostering of young people who had a sense of responsibility to the Party and to the nation.

Leading institutions such as Tsinghua University and Shanghai University also raised the idea of pushing a “curriculum sizheng” (课程思政), meaning that the teaching of sizheng would not be about taking a particular course in addition to regular coursework, but rather would be woven into the fabric of university teaching, which would require that teachers in all subjects consider ideological and political values in the teaching process. In effect this was a more discreet approach to forming the political ideas of students in higher education.

One unfortunate consequence of such blending of sizheng with other subjects could be their overt politicization. A now-deleted article published on the Wechat public account “Thinking About It” (楞个想) shared two photos of course guidance and instruction books for teachers in universities, including subjects like English, Chemistry, Biology, Finance, and so on. At first glance, these resemble other instructional materials, but there is a clear difference – these books are tailored for ideological and political education. They instruct teachers on how to systematically implant sizheng in the teaching of different subjects.

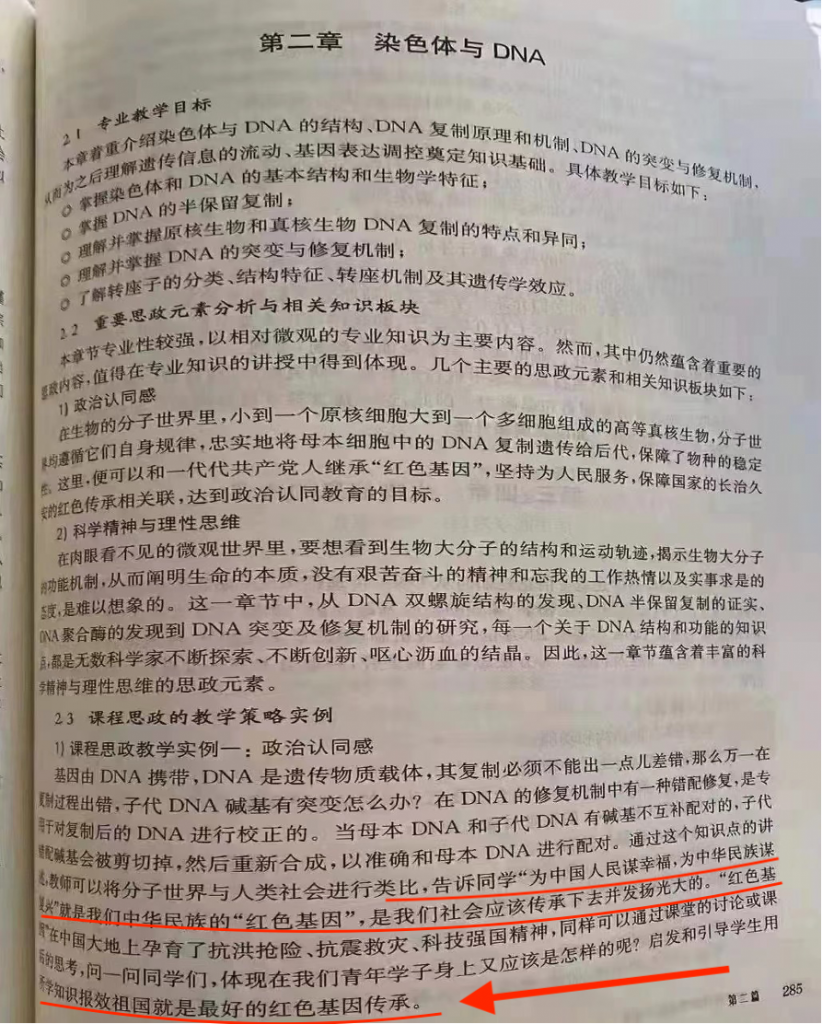

A second image from the removed WeChat post showed a page in the biology textbook. As the text discusses DNA, the teacher is encouraged to bring in the concept of “red genes” (红色基因), a reference to the revolutionary spirit and legacy of the CCP that has been a popular frame, or tifa (提法), in the Xi Jinping era. The textbook suggests that the idea of working and fighting for the prosperity of the nation is a character embedded in the DNA of all Chinese. “In the molecular world of organisms, from a tiny prokaryotic cell to the multicellular organism, DNA replicates from the parent call to the offspring, guaranteeing the stability of the species,” the text says, before adding an editorial note for instructors:

At this point, teachers can associate this with the concept of the red heritage passed between generations of communists who inherit ‘red genes.’ Teachers should tell students that is it necessary to adhere to the service of the people, and ensure the long-term stability of the country, in order to achieve the goal of political identity education.

The combining of ideological and political education goals with learning in different subjects is prevalent in Chinese higher education. Nearly every subject, in either open classrooms or private tutoring sessions, can be associated with the goals of sizheng.

The page in the textbook on biology explicitly links the study of the subject to patriotic goals and love of the CCP, encouraging an attitude of thankfulness and indebtedness, and concluding: “Inspiring and leading students to use scientific knowledge to repay kindness to the mother country is the best means of passing on red genes.”

The forced insertion of sizheng into higher learning has drawn criticism from many Chinese, though such criticism can be difficult to find given controls on online speech. In one post to Weibo, an internet user wrote: “Anyone with common sense would know that talk of ‘red genes’ is just a metaphor and an abstract idea. For a university biology text to link this in is just disrespectful to both science and politics, and totally absurd.”

Responding to this post, another user wrote: “If politics infiltrates into every aspect of life, I think this is terrifying.”

Sizheng in the Political Winds

The application of sizheng to education changes in China as political priorities change. When, for example, the State Council promoted its “double reduction” policy (双减政策) in 2021, which aimed to reduce the total amount and time spent on schoolwork and lessen the burdens on families from private cramming courses, ideological and political education was forced to change along with the entire education sector.

In September 2021, the Guangming Daily, run by the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department, published an article urging schools to take the opportunity of falling academic burdens on students to enhance the teaching of sizheng, weaving ideological and political education more tightly into the fabric of education and teaching.

How effective has the sizheng campaign been for the CCP over the past decade? Impact is sometimes difficult to measure reliably, but a report by the Chinese Communist Youth League’s China Youth Daily newspaper in 2016 following the above-mentioned national ideological and political conference indicated that changes in recent years had had a major impact, with 99.4 percent of the students in universities saying they deeply believed in the leadership of CCP as the trusted backbone of the Chinese people. “The students’ ideological love for the Party and the country, as well as for socialism, has been consolidated, their determination to follow the Party has been strengthened, and their confidence in the system has been further enhanced,” the newspaper concluded.

It is important to remember, of course, when reading such poll results, that a primary outcome of the relentless drilling of students in the need to approach subjects with political sensitivity should be university students who are well aware of the “correct” responses to such questions.

Stella Chen

The CMP Dictionary

C

D

F

G

M

N

P

S

- Scaling the Wall

- Science

- Second-Generation Reds

- Security

- Seeking Progress in Stability

- Seeking Truth From Facts

- Self-Revolution

- Seven Bottom Lines

- Six Adheres

- Smart Governance

- Sneaky Visit

- So-Called

- Socialite

- Soft Resistance

- Soul and Root

- Soundless Saturation / Quietly Nourishing

- Sovereignty

- Speaking Politics

- Streamlining Services

- Strong Cyber Power