When the government of Japan’s Kumamoto Prefecture introduced its popular Kumamon mascot in 2010 in a bid to draw tourists to the region, it was banking on the power of cuteness. The bet paid off. The signature black bear, with rosy red cheeks, generated more than a billion dollars for Kumamoto in just two years.

At the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, China has hoped to mirror this success with its own mascot, the now ubiquitous Bing Dwen Dwen (冰墩墩). In contrast to the forceful wolf-warrior image that China has projected internationally in recent years, the giant icy-shelled panda, with a rainbow-like silk ring encircling his face, is a softer and cuddlier alternative – perhaps Beijing’s answer to Xi Jinping’s call back in May last year to “build a credible, lovable and respectable image of China.”

But Bing Dwen Dwen also seems to be serving as an effective distraction at home and abroad, achieving another key objective during the Winter Olympics – ensuring that criticism does not win the day. For China’s government, the chubby panda, enormously popular by all accounts, has been the fluffy friend who launched a thousand fluff pieces.

Shortly after Bing Dwen Dwen appeared at the opening ceremony of the Winter Olympics, the Chinese media were full of reports about how shoppers queued up in Beijing’s Wangfujing shopping area, some waiting as long as 11 hours in the bitter cold, hoping to take away their own soft souvenirs.

And as athletes at the Games complained about poor planning for cold weather, abysmal food and other problems at the event, the official Xinhua News Agency went after the hard news about the country’s favorite softie. “From stands to signs and posters, the cute panda is ubiquitous at the Olympic facilities, and has been well received among international participants, even being awarded to medalists who hold one up on the podium, eliciting huge ovations from spectators,” the news agency reported.

The mascot, Xinhua added, “is expected to become a shared memory of the whole world.” This remark was reminiscent of remarks made back in December by Wang Wenbin of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, when he linked the fluffy mascot to Xi’s foreign policy notion of a “community of shared destiny,” saying in response to a question from The Paper that “we will all join hands to bring warmth to the world and work together for a shared future just like the lovely mascots ‘Bing Dwen Dwen’ and ‘Shuey Rhon Rhon.’”

The China Daily, published under the government’s Information Office, mentioned that Xi Jinping had gifted a pair of the mascots to Albert II, Prince of Monaco, with the hope he would take them back to his children. The newspaper also quoted a souvenir shop employee as reporting that “the mascot is very popular with foreign reporters covering the Games.”

Foreign reporters covering the Games were sometimes asking more pointed questions of this year’s host, in stark contrast to the softball questions lobbed by their Chinese counterparts. Meanwhile, reports from nearly all state media, including China Daily, noted that Bing Dwen Dwen had dominated discussion on the Chinese social media platform Weibo, earning more than 2.5 billion views – roughly two views for every member of China’s vast population.

There were other explanations, however, as to why Bing Dwen Dwen seemed to dominate discussion. For several days after the opening ceremony, the mascot remained at the top of sports topics on Weibo, even besting clearly relevant breaking sports topics, like the attention paid to Japanese figure skater Yuzuru Hanyu, who received an outpouring of adoration from Chinese online who mourned his failure to defend his Olympic title.

Were internet authorities baking Bing Dwen Dwen’s success into top platforms, fluffing up cyberspace with manufactured trends?

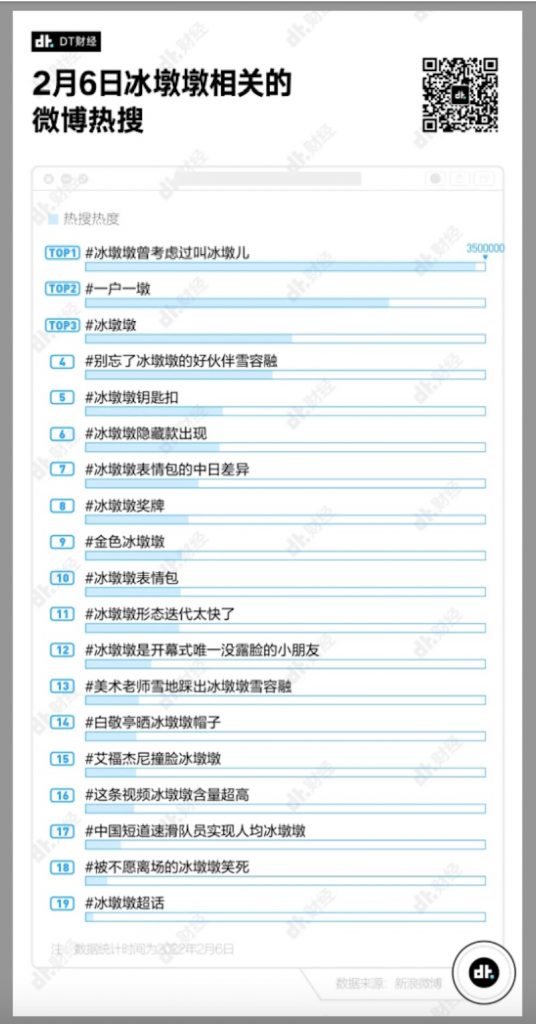

According to DT Caijing (DT财经), on February 6 alone there were 19 related trending topics on Weibo about Bing Dwen Dwen. The Sydney Morning Herald reported 3 days later that in fact around 20 percent of the accounts behind 30,000 posts about the mascot had been created within the previous month, suggesting that Bing Dwen Dwen was being artificially pushed out to center stage by a concerted publicity campaign.

Also dominating the headlines in state media were stories about the woeful scarcity in Ding Dwen Dwen supply, as though “adequate supply in the market” was a question of national urgency. “Production of Bing Dwen Dwen merchandise increased to ensure adequate supply,” said a headline at Xinhua.

On its official Weibo account, the state-run broadcaster China Central Television (CCTV) wrote, in a post accompanied by a collage of Bing Dwen Dwen merchandise: “If we can’t get our Bing Dwen Dwens, then we can only collectively take part in the Winter Olympics!”

Posts like this one occasionally drew sarcastic remarks. Referencing Xi Jinping’s call to close the yawning wealth gap in China by promoting “common prosperity,” one user commented under the CCTV post: “Please make sure every household in China is able to get a Bing Dwen Dwen. We need to reach the ultimate goal of common ownership of Bing Dwen Dwen.”

But such mockery was rare. Most users simply expressed their fervent wish to get their hands on their own Bing Dwen Dwen.

Up to the time of posting, Bing Dwen Dwen’s official store on Tmall, a major e-commerce platform, still showed most products out of stock, with some subject to daily sales quotas. And if the focus on Bing Dwen Dwen fluff was meant to bend foreign headlines in the direction of Chinese ones, the ploy seems to have worked. Reports on the mascot’s scarcity followed at Quartz, the South China Morning Post, Reuters, the Washington Post, NPR and the New York Times. So perhaps the mascot was indeed popular with foreign reporters inside the Olympic bubble?

The official push to drown out criticism and promote positivity through the irresistible fluff of Bing Dwen Dwen has also prompted a revealing suspension of China’s usual regulation of mad buying sprees on consumer protection grounds. One recent example was a boycott by Chinese market authorities of meal promotions by KFC outlets in China in cooperation with Pop Mart, the Chinese seller of toy collectibles. Under the campaign, KFC meals had been sold with random “blind box” inserts of Pop Mart toys, and in one case as customer was reported to have purchased more than 100 meals in hopes of finding collectibles inside. The craze was deemed to be harmful to consumers.

Such concerns have apparently been dropped in the case of the Bing Dwen Dwen craze – even though Bing Dwen Dwen is similarly being sold with “blind box” inserts, and at much higher prices than for the KFC campaign. On February 8, San Francisco-based non-fungible token (NFT) marketplace nWayPlay announced that its Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics blind boxes containing Bing Dwen Dwen pins would go on sale at a price of 99 dollars each, though sales are limited to five per person.

For years, China has anxiously pushed to increase its soft power, and combat what leaders view as unwarranted criticism and the domination of “global public opinion” by the West. In Bing Dwen Dwen, perhaps, China has found a softer way through a vexing problem. In related coverage on February 9, Xinhua News Agency said that the heart-warming Bing Dwen Dwen was “not just a manifestation of China’s increasing cultural soft power, but also an expression of China’s comprehensive national power.”

Those may seem hard words for such a soft mascot. But perhaps Bing Dwen Dwen’s designer said it best in an interview for the same report: “We are no longer desperate to prove anything to the world,” he said. “It is enough for us to express ourselves calmly.”