Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy walks under a camouflage net in a trench as he visits the war-hit Donetsk region in eastern Ukraine, Dec. 6, 2021. Image by manhhai available at Flickr.com under CC license.

Throughout most of the world, the ongoing conflict in Ukraine is “Russia’s war.” But as international media have reported, China has refused to talk about an “invasion” or a “war” in the two weeks since Vladimir Putin launched his military attacks. In its first press conference on February 24, the day attacks began, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs set the tone by saying that China had noted Russia’s “special military operation in eastern Ukraine.”

Minister of Foreign Affairs Wang Yi (王毅) seemed finally to break the pattern Thursday in a meeting with his French counterpart, Jean-Yves Le Drian, in which he said that China supports “a ceasefire to stop the war.” Nevertheless, voices critical of Putin, or even calling for peace, continue to be systematically removed from Chinese social media platforms, and content critical of Ukraine and the West, particularly the United States, proliferates.

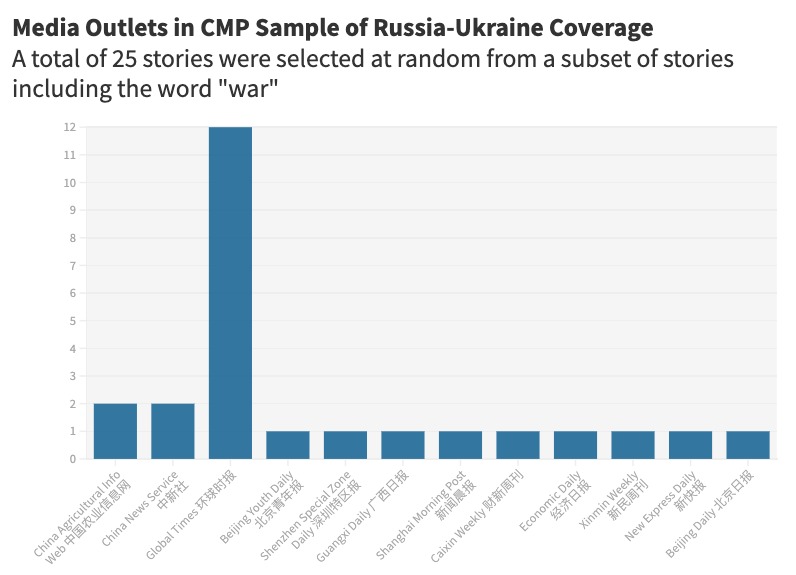

To examine China’s framing of “Russia’s war” more closely, the China Media Project studied a randomized sample of reports over the past seven days. From among 721 total reports returned in the Wisenews database including the term “Russia-Ukraine” (俄乌) in mainland China, we isolated a subset of these reports including the word “war” (战争), yielding a total of 114 articles (87 print and 27 online). Randomizing these results we focused on just 25 articles for analysis.

The “war” references in our set of Ukraine-related stories were not necessarily labels applied to the conflict in Ukraine, but they could sometimes offer interesting insights into when and how Chinese media use “war” in reference to the war, its causes, and its development.

Operation, Conflict and War

Of the articles studied in our sample 12 were from the Global Times (环球时报), accounting for 48 percent of the total. It is clear that the Global Times is a dominant voice when it comes to the coverage of foreign affairs in China, and it has had an outsized presence in overall overage of the Russian-Ukraine war. The only other news sources to have multiple articles on our sample were the official China News Service (2), and China Agricultural Info Web (中国农业信息网), a comprehensive agricultural information platform that was launched in 1996 by the Information Center of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (2).

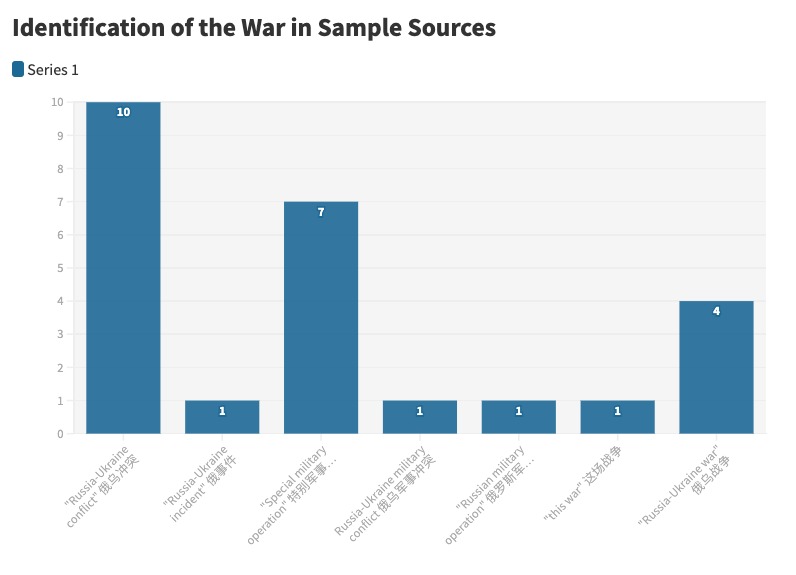

How was the war in Ukraine identified in the CMP sample? And how did articles in the sample use the word “war”?

A sizable group (10 articles) referred to the war as the “Russia-Ukraine conflict” (俄乌冲突), while a slightly smaller number (7 articles) referred to the war as a “special military operation” (俄罗斯军事行动). Next came “Russia-Ukraine war” (俄乌战争) with a total of four articles, followed by “Russia-Ukraine military conflict” (俄乌军事冲突), “Russian military operation” (俄罗斯军事行动) and “this war” (这场战争) with one each.

One fact we can note immediately is that while the war has generally not been called a war over the past week in the Chinese media, with 80 percent of media referring to it as some form of “operation” or “conflict,” the “special conflict” language is by no means universal, and there is some slight variation, suggesting that there may be some grey areas when it comes to propaganda-related restrictions and how these are being applied.

“Special Military Operation”

Beginning with the label “special military operation,” it quickly becomes clear that this is label being used almost exclusively by central-level media and newswires. The 10 articles including the term come from five media sources, including the Shenzhen Special Zone Daily (深圳特区报), Guangxi Daily (广西日报), Shanghai Morning Post (新闻晨报), the Global Times and China News Service. But there are in fact just three sources for these syndicated stories: Xinhua News Agency, China News Service and the Global Times. The Shenzhen Special Zone Daily, Guangxi Daily, and the Shanghai Morning Post all run reports from Xinhua News Agency.

While two of the Global Times stories in our subset use the term “special military operation,” it’s worth noting that the newspaper actually varies in its use of labels, most often referring to the war as the “Russia-Ukraine conflict,” but also referring to it in two separate articles as the “Russia-Ukraine war.”

Here are several of the contexts in which “war” is mentioned in articles referring to the war as a “special military operation,” arranged chronologically:

Global Times

March 8, 2022

Headline: “U.S. mulls more extreme sanctions, Russia publishes ‘unfriendly list,’ Russia vows to accomplish operational goals in Ukraine” (美国酝酿更极端制裁 俄方公布”不友好名单”俄誓要完成在乌行动目标)

[Regarding sanctions on Russia] If this measure is put into action, it will inevitably further anger Russia and increase the risk of war spillover.

AFP said it would be the first event Lavrov has attended abroad since the war led to Russia’s isolation by the West.

Global Times

March 9, 2022

Headline: “Safeguarding national assets and making it harder for foreign companies to exit, Russia strikes back at Western economic sanctions” (维护本国资产安全 增加外企退出难度 俄出手回击西方经济制裁)

The secretary of the General Committee of the United Russia party, Andrei Turchak, said the party proposes to nationalize the factories of foreign companies that announced their withdrawal from the Russian market and stopped production in Russia during the special military operation against Ukraine. According to the Russian newspaper Kommersant on [March] 8, he said that the West’s “sanctions war” against Russia, which includes not only the government but also private companies, is tantamount to “deliberate bankruptcy.”

China News Service

March 9, 2022

Headline: “Zelensky asks the West, “Where is the aid?” — will the situation in Ukraine change? (泽连斯基质问西方”援助在哪”,乌克兰局势将变?)

On [March] 8, after realizing that NATO is not ready to accept Ukraine, Zelensky said that he “has lost interest in this matter.” He believes that NATO is “afraid of confrontation with Russia.” Zelensky stressed again that he is ready to open a dialogue with the Russian side. “There should be an end to the war, and we should sit down and negotiate.” The Ukrainian side can seek a compromise with Russia on “how to live” with the people of the Crimea and Donbas regions, he noted.

Shanghai Morning Post

(Xinhua News Agency)

March 11, 2022

Headline: “Ukraine’s foreign minister: the parties failed to make progress on a ceasefire” (乌克兰外长:双方在停火问题上未能取得进展)

According to Xinhua, Ukrainian Foreign Minister [Dymtro] Kuleba said on October 10 that Ukraine and Russia have failed to make progress on the ceasefire issue and he is ready to continue negotiations with the Russian side to end the war.

In all four of these examples, it is clear that responsibility for “war” lies with Ukraine and with the West. In the case of both the China News Service report and the Xinhua report via the Shanghai Morning Post, the implication is that “war” is something for the Ukrainian side to stop by coming to the table – not something that has been waged against the country. In both of the Global Times reports, the only act of “war” is the “sanctions war” (制裁战争) that has been brought on Russia by the West, and which risks “war spillover.”

“Russia-Ukraine Conflict”

Here are several of the contexts in which “war” is mentioned in articles referring to the war as the “Russia-Ukraine conflict,” arranged chronologically:

Shanghai Morning Post

March 6, 2022

Headline: “Self-reliance and self-improvement in science and technology to win the initiative of development” (以科技自立自强赢得发展主动)

The sanctions and counter-sanctions between the U.S. and the West and Russia are a game at the level of war.

Global Times

March 9, 2022

Headline: “Russia says destruction of U.S. nuclear facilities was ‘self-directed’” (俄称乌核设施被毁是”自导自演”)

[IAEA Chief] Groce said, “We must act to help avoid a nuclear accident in Ukraine that could have serious consequences for public health and the environment. We can’t afford to wait.” He also said he was prepared to meet with officials from both countries at a location agreed to by Ukraine and Russia to ensure the safety of nuclear facilities in the event of an escalating war in the future, which would require ensuring the “physical integrity, communication channels and supply chain” of nuclear facilities.

Beijing Youth Daily

March 11, 2022

Headline: “Russian and Ukrainian foreign ministers meet in Antalya, Turkey” (俄乌外长在土耳其安塔利亚举行会晤)

The meeting took place in the small town of Belek outside Antalya. After the meeting, the Russian and Ukrainian foreign ministers held separate press conferences on the meeting, with Ukrainian Foreign Minister Kuleba saying that the Ukrainian and Russian sides had failed to make progress on the ceasefire and that he was ready to continue negotiations with the Russian side to end the war. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said that Russia is ready to continue dialogue with Ukraine.

Beijing Daily

March 11, 2022

Headline: Paradox of sanctions against Russia highlights Europe’s strategic autonomy dilemma (对俄制裁悖论凸显欧洲战略自主困境)

Since the Crimean War in 2014, the EU has failed to make substantial progress in reducing its energy dependence: in 2020, total EU gas imports from Russia are 26% higher than in 2010.

As in the previous examples, these mentions of “war” in the context of the “Russia-Ukraine conflict” largely place responsibility with Ukraine and the West. It is Ukraine, in the Global Times story, that has (according to Russia sources) destroyed its own nuclear facility at Chernobyl, exposing all to “serious consequences.” It is the Ukrainian side that is mentioned in relation to “war” in the context of negotiations. And the only obvious “war,” as clear in the Shanghai Morning Post story, is that instigated by the US through its sanctions.

“Russia-Ukraine War”

Here are several of the contexts in which “war” is mentioned in articles referring to the war as the “Russia-Ukraine war,” arranged chronologically:

Xinmin Weekly

March 7, 2022

Headline: “Witnessing Her Decline” (眼見她的衰落)

[About Sun Guang, a student studying abroad in Ukraine]: That was also the most difficult time Sun Guang had experienced in Ukraine before this recent Russian-Ukrainian war broke out.

In the early hours of February 24, 2022, Russia launched a war against Ukraine, and artillery fire rang out in Kiev immediately afterwards. Sun Guang was the first to call his Chinese friends he knew from all over Ukraine, urging them to be safe and offering to help at any time.

China Agricultural Info Web

March 9, 2022

Headline: “Wheat is starting to cool down, what about corn?” (小麦开始降温,玉米呢)

As the Russian-Ukrainian conflict escalates, international food prices have soared. Since the escalation of the Russia-Ukraine conflict on February 24, international wheat and oil have risen several times, and corn is also climbing. On March 7, corn futures at the Chicago Board of Trade closed with mutual gains and losses, but trends were weak overall. With our country’s integration into the international community, the global butterfly effect impacting us [in China] is quite high. Xinhua News Agency commented that the Russia-Ukraine war has prompted a spike in energy and commodity prices, including wheat and other grains, further exacerbating inflationary pressures stemming from supply chain disruptions and the recovery from the covid epidemic. Affected by the war, Black Sea ports have suspended transport.

China Agricultural Info Web

March 9, 2022

Headline: “Foreign sugar continues to rally, Zheng sugar futures prices stabilize and rebound” (外糖继续反弹 郑糖期价企稳回升)

Friday night raw sugar futures prices continue to rise, coupled with the continued sharp rise in crude oil prices, and this is expected to boost the trend of Zheng sugar futures prices today. Last week, sugar futures prices rebounded weakly and positions dropped significantly. Last week the Russia-Ukraine war opened, resulting in the price of crude oil rose sharply, affecting the Brazilian sugar alcohol ratio, which in turn affected the supply of raw sugar in the international market, foreign sugar prices continued to move higher.

Global Times

March 10, 2022

Headline: “Russia plans to investigate US biological lab in Ukraine” (俄计划调查美在乌生物实验室)

The fate of U.S. biological laboratories in Ukraine has raised strong concerns since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war. U.S. government data show that Washington has 26 biological laboratories and other related facilities in Kiev. Russian forces have found more than 30 biological laboratories in Ukraine that could produce biological weapons, according to the Russian newspaper Opinion. At a U.S. Senate hearing on the 8th, [Under Secretary of State Victoria] Nuland also claimed that if there is a biological or chemical weapons attack in Ukraine, then Russia must be behind it.

Global Times

March 10, 2022

Headline: “Famous Russian designer is ‘banned’” (俄知名设计师被”封杀”)

The New York Post reported on August 8 that Ralph Toledano, the Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode, the organizer of Paris Fashion Week, had confirmed to the media that [Russian designer] Valentin Yudashkin had been “banned,” saying that the organizer had tried to find out the designer’s position on the Russia-Ukraine war, but it was clear that he was on the Russian side. Toledano also said that Yudashkin’s ties to the Russian military were an important factor in the organizers’ decision to ban him from attending.

Among these five stories in our subset using the term “Russia-Ukraine war,” only the first Global Times story clearly follows the pattern of anti-American coverage, essentially passing along discredited Russian propaganda about the presence of US biological weapons facilities in Ukraine. The second Global Times story is plays it rather straight in sharing a report from the New York Post about the exclusion of Russian designer Valentin Yudashkin from Paris Fashion Week. The Global Times, in fact, has been rather inconsistent in its labelling of the war, though reports blaming the West have predominated at the outlet. In several stories today (here and here), the outlet persists in calling the war a “special military operation.”

China Agricultural Info Web is an interesting exception in coverage of the war. It has no explicit agenda, other than informing its target audience about corn futures and sugar prices, and the “Russia-Ukraine war,” which is has no problem calling a war, is simply important background.

But the first story in the “Russia-Ukraine war” list above is worth singling out because it is a reminder, however faint, that professional reporting, and more creative thinking about stories, still persists in China even under the thick cloud cover of domestic media control and the opportunistic pushing of pro-Russian and anti-West propaganda. Based in Shanghai, Xinmin Weekly is published by Shanghai United Media Group (SUMG), which also publishes Jiefang Daily, the Shanghai committee of the CCP. Xinmin Weekly is part of what could now be considered the old guard of professional journalism emerging in China from the 1990s under an environment of commercial experimentation in the media.

In reporting on Ukraine, Xinmin Weekly takes the interesting approach of writing a feature story centered on Sun Guang (孙光), a 19 year-old Chinese student in Ukraine whose life is upended by the war. The story opens unflinchingly: “In the early hours of February 24, 2022, Russia launched a war against Ukraine . . . “

Another interesting outlier in our subset is story #21, which happened to come from Caixin Weekly (财新周刊), the business and current affairs magazine published by Caixin Global under the professional leadership of Hu Shuli (胡舒立). This is the story in our group referring to the war in Ukraine simply as “this war” (这场战争), and it is – as one would generally expect from Caixin – in a class of its own.

Called “Russia and Ukraine Reorganize the World” (俄烏重組世界), the cover story appeared on March 7, in the last edition of the magazine. Like the Xinmin Weekly story, it begins with a reference to the “war” in Ukraine that does not pull punches:

In the midst of this war in the spring of 2022, the Crimean Peninsula, the site the last major conflict over sovereignty between Russia and Ukraine in 2014, has become a key departure point for the Russian military’s offensive push deep into Ukraine.

Not only does the Caixin Weekly story begin with acknowledgement that the current conflict is a “war” and not a “special military operation,” but it also provides a clear and active sense of Russia as the primary agent, its “offensive” pushing deep into Ukraine.

Though just two cases in a torrent of US-blaming, West-shaming Chinese content on Ukraine, the Caixin Weekly and Xinmin Weekly stories are a reminder that central-level newswires, the Global Times and the foreign ministry are not a complete reflection of Chinese views. Nor are they fully reflective of Chinese reporting. Despite the immense changes under Xi Jinping, and despite the preponderance of “pro-Moscow posturing” on Chinese social media, professionalism in the Chinese journalism and information space can still be quietly insistent.