Image by Voice of America available at Wikimedia Commons under CC license.

For analysts of China’s political discourse, this has been a boisterous week. Ever since Xi Jinping reached the podium in the Great Hall of the People on Sunday to unveil his soaring report, the Chinese Communist Party’s latest rhetorical Tower of Babel, experts have probed its bricks and joints, eagerly taking its measure.

Data being the new intellectual currency, many have also bravely tackled Xi’s report with the clarifying medium of the spreadsheet. The result has sometimes been to heap confusion atop an already mystifying report.

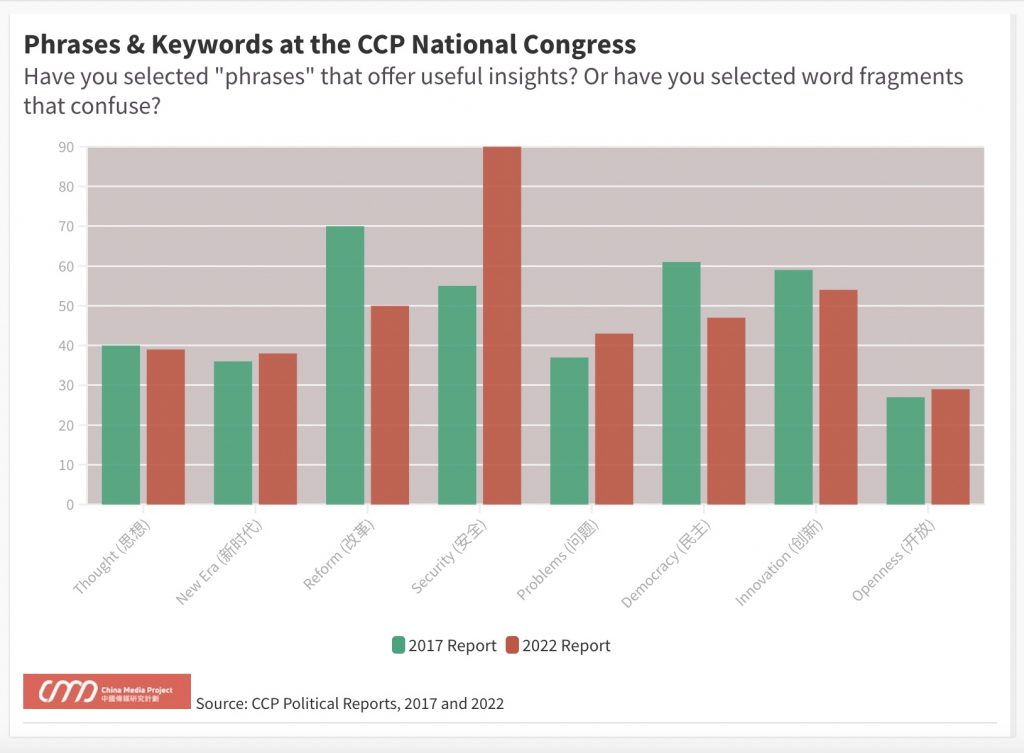

To explain, I offer below an example of my own invention, a mashup of three separate graphs offered online this week from well-regarded political experts. The graph was created using my own counts within the full-text versions of the two most recent CCP political reports (政治报告) of keywords being identified by others as deserving analysis.

For starters, phrases, slogans, and buzzwords can be extremely useful tools in understanding China’s political discourse. As the reader of CMP’s “China Newspeak” section will know, we obsessively research the specialized language formulations the CCP uses to frame its ideas and signal its collective moods. These are know as tifa (提法), and we even collect them in our CMP Dictionary — like bug specimens on a pinning block.

But which phrases and keywords should we be seeking? What are the basic building blocks of CCP discourse? This question is crucial when it comes to readings of Party texts, contemporary and historical.

The proliferation of keyword charts this week suggests to me that when it comes to the analysis of China’s political reports, we all might be in need of some “rectification of names” (正名) — to borrow carelessly from Confucius.

Dimming Distinctions

If we tabulate a term like “democracy” (民主), won’t this have something to reveal about political trends in China?

We might hypothesize that greater chatter about “democracy” in a high-level CCP document would have to indicate some level of either support or criticism of democracy. In the case of Xi’s most recent report, there is an apparent downturn in the use of the word “democracy,” as my graph clearly shows.

Is this notable?

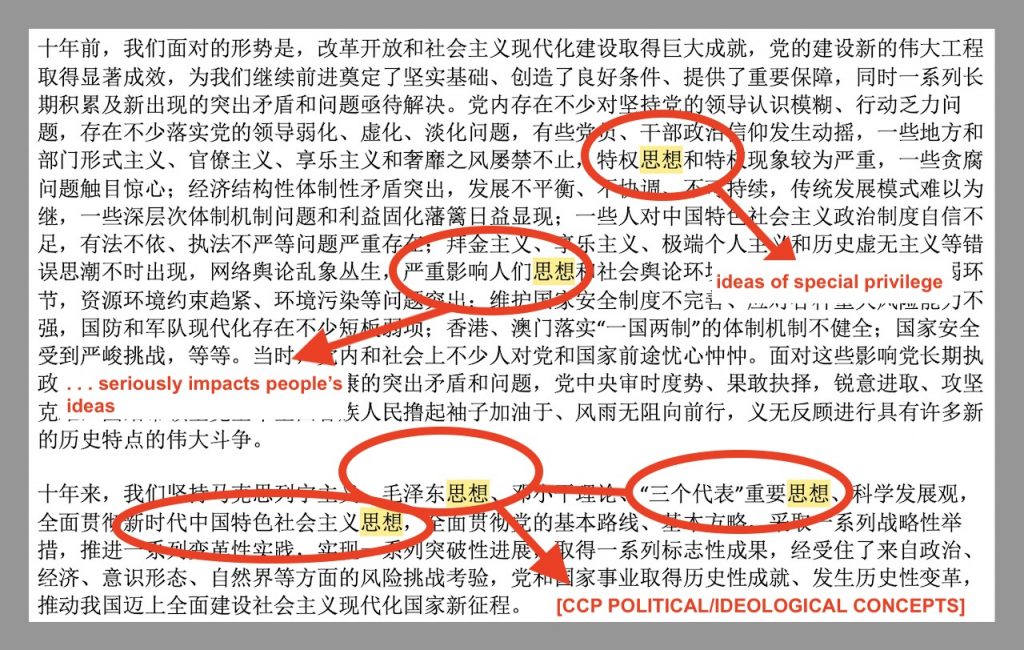

The problem is a simple one. The two characters that have been translated here as “democracy,” minzhu (民主), could mean any number of things in Xi Jinping’s text, and they might in fact be little more than subordinate pieces of larger phrases. They might be adjectives rather than nouns.

To illustrate the point, here are five separate appearances of minzhu in the political report to the 20th National Congress of the CCP:

1. “whole-process people’s democracy” (全过程人民民主)

2. “democratic centralism” (民主集中制)

3. “the democratization of international relations” (国际关系民主化)

4. “strengthening unity and cooperation with people from democratic parties” (加强同民主党派和无党派人士的团结合作)

5. “supporting the main status of the people” (坚持人民主体地位)

In the case of phrase 1 above, we have a concept that has been newly emphasized by Xi Jinping, the idea that China, unlike the countries of the West, is truly democratic and deliberative, which the leadership has now dubbed “whole-process democracy,” or more properly “whole-process people’s democracy.” This is an old term contained inside a newer phrase. The older term is “people’s democracy” (人民民主), the Marxist-Leninist concept that emerged after the Second World War.

I won’t go deeply into these phrases and their history. But suffice it to say that these concepts are built on the foundation of CCP supremacy, and on the assumption that its actions, whatever they are, reflect the will of the people. Tellingly, Xi’s democracy neologism is more vocal in its response to US actions on global democracy, such as Biden’s summit in late 2021, than it is in laying out the real mechanisms of citizen participation in governance in China.

Similarly, phrase 2, “democratic centralism,” is a Leninist revolutionary strategy that seeks to combine centralized Party control and the notion of free and open discussion. History has shown through successive waves of suffering in both China and the Soviet Union that “democratic centralism” is in practice far more centralist than democratic.

Both 1 and 2 are about governance, though it should be clear to most readers that they are not at all about true democratic governance. In fact, a strong case could be made that increased mention of either term in the CCP discourse corresponds to a reversal in terms of real interest in truly deliberative mechanisms.

As for 3, this use of minzhu has nothing whatsoever to do with issues of domestic governance. The context here is China’s foreign policy and the view that the current international order is not suitable or fair for China and developing countries. A system is needed globally, therefore, that is more “democratic.” This is about balancing out the dominance of the United States and the West, as China understands it.

Moving on to phrase 4, this is a reference to so-called “democratic parties” in China, which fall under the CCP’s united front (统一战线) and have nothing whatsoever to do with real democratic governance. These parties are subject to strict control and are completely compatible with centralized — and centralizing — Party rule.

Finally, in phrase 5, we have an oops moment, a false positive for minzhu arising from the close proximity of the word renmin (人民), or “people,” and zhuti (主体), or “main.” I include it because data-led approaches to documents like the congress report are likely to throw up such issues when the Chinese language is broken up to its root level in this way.

If we are, as one researcher suggested, looking at the “relative weights of phrases” as a means of insight, then surely it matters that the above instances of minzhu are in practice semantically distant. What exactly are 61 or 47 occurrences of minzhu supposed to signify?

What’s the Problem?

The gaps become more serious when choices like “problem,” or wenti (问题), are crunched into visualized data, as also happened this week.

The word “problem” occurred 37 times in the 2017 report, and 43 times in the 2022 report. So perhaps we should infer from this that CCP leaders have roughly the same degree of concern about unspecified things that are happening in China and the world in 2022 as they did in 2017.

Any Chinese speaker who slows down for just a moment will register that the word wenti can refer an “issue,” “question” or “problem.” The question of where to eat lunch can be a wenti, as can the more pressing question of how to face a life-changing problem.

What are the basic building blocks of CCP discourse? This question is crucial when it comes to readings of Party texts.

In Xi Jinping’s 2022 political report there are “political problems” (政治问题) and “economic problems” (腐败问题), both crowded into the same textual space as “corruption problems” (腐败问题), of which they are examples. But there are also “major questions” (重大问题), those immense decisions that the leadership claims to make with unparalleled competence. Further, there is the issue of poverty (贫困问题). And finally, there are real, immense, and looming things like the “Taiwan question” (台湾问题), which was mentioned four times in Xi’s report this week.

These examples suffice, I hope, to introduce the problem, issue, or question invited by number-crunching the word wenti in Party documents.

Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Phrase?

There are rare instances where these fragmented pieces of the Chinese language can actually be mildly, incidentally, revealing. One example is the word “security,” or anquan (安全), which has ballooned in Xi’s 2022 report, as my graph above shows. Many of the references in the report deal with a host of CCP priorities under the broader mantle of “national security,” and these permutations of national security all contribute to a general rise in the word.

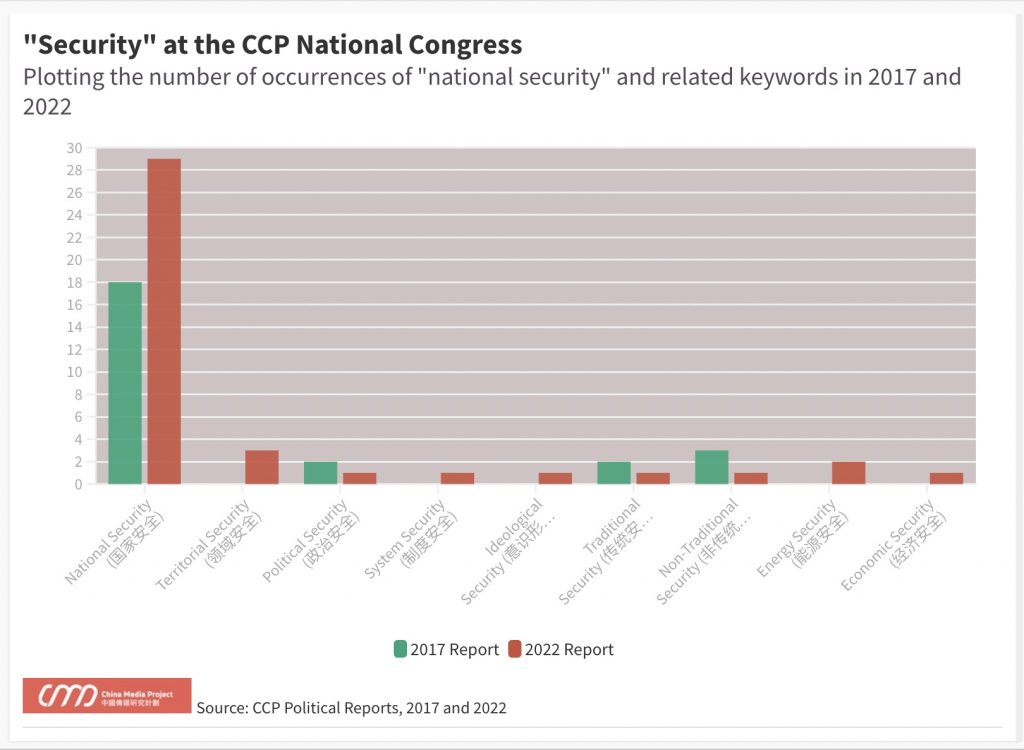

But there is also mention, for example, of the need for “reliable and secure supply chains,” the need to ensure “work safety” (安全生产), and China’s participation in global “safety standards” (安全规则). If the interest is to compare the degree to which the 2017 and 2022 reports deal with the broader issue of national security, then the proper phrase to explore would be guojia anquan (国家安全), along with mentions of related terminologies.

Did new aspects of national security appear in 2022 that were absent in 2017? Yes, in fact. This year’s report throws in “system security” (制度安全), about the preservation of the regime, and “ideological security” (意识形态安全), about safeguarding the theories and principles of the Party. The simple hard work of sussing out the contexts and histories of phrases like these would in this case be far more insightful.

But if we wish to visualize the terminologies, we might first isolate the full phrases within the national security domain, and then plot the occurrences in political reports over time. We might get something like the following graph.

This graph has the advantage of at least isolating those keyword mentions that are related to national security, and it accurately shows a fairly substantial increase in related buzzwords — considering that the political reports are nearly identical in length. The term “national security” is used 60 percent more in the 2022 report than it was in 2017. Meanwhile, we see the emergence in the 2022 report of new related terms elaborating the security concept.

The basic point here is that the analysis of CCP discourse should be built on full-fledged keywords like those used in the arena of national security. Sometimes these are terminologies that are shared between the Chinese political context and our own languages, with key differences (see our partner Decoding China project). And sometimes they are terminologies that are entirely unique to CCP discourse, which brings us back full circle to those building block terminologies I referred to earlier as tifa.

Tifa are crucial for researchers to grapple with because there are whole sets and hierarchies of such buzzwords and phrases regularly used by the Party, falling in and out of favor as the political winds change. The phrases have layered moods and meanings. Some may have more liberal, pro-reform histories, associated with political moments in the CCP’s contemporary past; while others hiss with hardline warnings, echoing the painful pre-reform decades, or the dark notes that prevailed in the wake of the bloody Tiananmen Massacre in 1989.

As deadened as they may sound as they are intoned from the podium in the Great Hall of the People, tifa are alive and changing, and they have their secrets to tell.

We have, in fact, one rather ominous example of this in Xi Jinping’s political report this week that takes us right back to the question of democracy — and has nothing whatsoever to do with the word minzhu.

Political Reform, Count Me Out

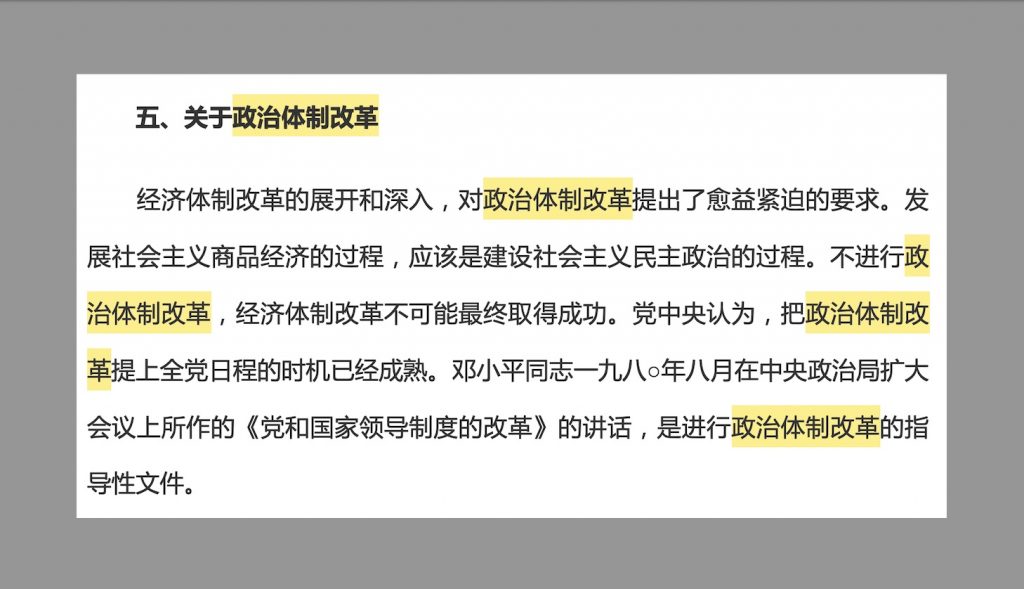

Throughout China’s reform era, the phrase “political reform” (政治体制改革) has been used within the CCP to point to the need to consider systemic approaches to greater public participation and oversight. Building on the reform spirit of the 1980s, the phrase rose to prominence in the political report delivered by Zhao Ziyang (赵紫阳) to the 13th National Congress in 1987, where it was given a special section, and appeared in the header of that section.

“The unfolding and deepening of the reform of the economic system has put forward increasingly urgent requirements for the reform of the political system,” said Zhao Ziyang. “The process of developing a socialist commodity economy should be the process of building socialist democratic politics.”

The idea in the late 1980s, voiced clearly in Zhao’s speech, was that political reform should proceed in step with economic reform. In line with these convictions within the Party, “political reform” rose rapidly from 1986 through 1988, taking center stage among the cast of characters in the CCP lexicon.

From the early 1990s onward, following the harsh crackdown on the pro-democracy movement in 1989, “political reform” alternatively faded and returned. But it never vanished, always lurking in the background, awaiting its opportunity.

Those whose memories reach back to the Hu Jintao era will recall that Premier Wen Jiabao (温家宝), on the doorstep of the changes that would come in the next administration, made repeated calls for political reform in 2010 and 2011, culminating in a very public address mentioning political reform at the World Economic Forum’s Summer Davos in Dalian in September 2011.

As deadened as they may sound as they are intoned from the podium in the Great Hall of the People, tifa are alive and changing, and they have their secrets to tell.

Stubbornly clinging on, the phrase has appeared in every political report at every CCP congress since 1987. In both the 1997 and 2002 reports by Jiang Zemin, it was mentioned in the section header (with five and seven nods to the term, respectively, in each report.) In 2007, “political reform” appeared five times, though shoved out of the section header.

In 2012, by which time outgoing Premier Wen Jiabao’s steady speech-making on the phrase had for some inspired cautious hope, “political reform” returned to the section header, which read: “Adhering to the path of socialist political development with Chinese characteristics, and promoting political reform.”

By the time the 19th National Congress rolled around in 2017, Xi Jinping’s colors had become terrifyingly clear. But still, “political reform” lingered, with a single mention in his report that year of the need to “actively and steadily promote political reform.” This appearance marked the term’s 30th anniversary in the CCP’s most important policy address.

Moving ahead to this year, what does the performance of “political reform” in Xi Jinping’s latest report tell us about the state of democratic politics as a stated ambition of the CCP?

In Section 6 of the report this week we can find mention of “socialist democratic politics” (社会主义民主政治), the phrase Zhao Ziyang wove into his notion of political reform. But it is treated not as an urgent prerogative but rather as a fait accompli. Xi Jinping claims that “whole-process of people’s democracy is the essential attribute of socialist democratic politics.”

But the real secret lurking in Xi Jinping’s political report — one that tells us quietly and convincingly that the “New Era” is about one man’s grasp for power — is the one that won’t be entered into our spreadsheets.

For the first time in almost 40 years, “political reform” is gone.