Tracking Control

Comedy, Under the Watchful Eye of the State

Li Haoshi performs on stage. SOURCE: Li Haoshi’s Weibo account.

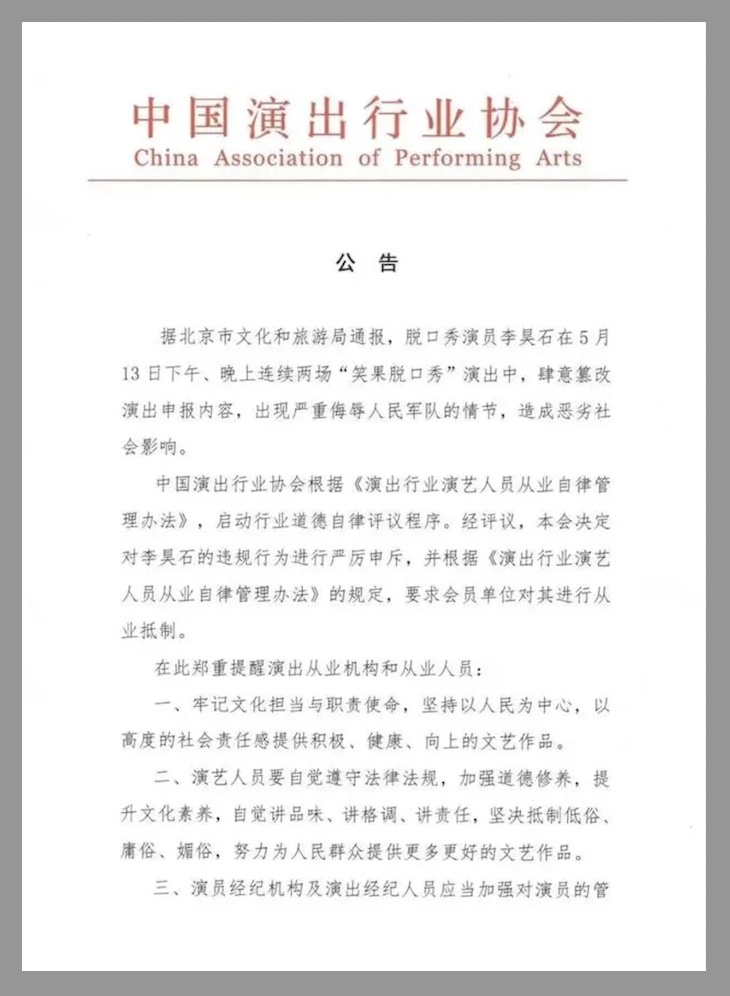

On Tuesday this week, China’s official Xinhua News Agency harshly criticized comedian Li Haoshi (李昊石), who is alleged to have insulted the People’s Liberation Army with a joke during a performance over the weekend. In the latest development, the China Association of Performing Arts (CAPA), which identifies itself as a non-profit social organization voluntarily formed by performance operators and practitioners, issued a strongly-worded statement late yesterday calling on all members to boycott Li — effectively ending his career as an artist in China.

The statement from CAPA alleges that “circumstances emerged [in Li’s performance] that insulted the people’s military, with nasty social consequences,” and it reminds all performers and enterprises in the culture space of their obligations to uphold decency and abide by the country’s laws and regulations.

But what exactly is the CAPA? And how does such a voluntary professional association have the power to enforce a ban on an individual performer?

Reading behind the news of the CAPA statement, which is being reported across official media today, can offer a glimpse into how the Chinese Communist Party exercises political and ideological control over culture and entertainment — and indeed many other areas — through organizations that apply Party-state power while seeming on the surface to represent broader interests.

A Professional Front

Formed in 1988, the CAPA began as an association of managers in the performing arts, and in 1993, as China’s media and culture industries entered a new period of development, the association morphed into a group also purporting to represent individual performers, with special divisions for areas like dance, drama, tourism performance and so on.

Like all professional associations in China, the CAPA claims to be voluntary (自愿) in nature. However, as the Li Haoshi case demonstrates, it clearly has a mandate to enforce political and cultural guidelines in ways that underline its quasi-official status. It is best understood, therefore, as an enforcement body of the Chinese state that networks with performers and enterprises in order to more closely apply political guidelines (the real goal of the “professional” front). At the same time, whenever necessary, the professional association can sanitize official actions, giving them the appearance of having emerged from professional consensus.

The organization’s official charter provides one of the first clues to its crucial role in enforcing CCP guidelines for the arts, and more fundamentally upholding the leadership of the Party.

Article 3 of the charter lays out the ideological commitments of the association — to Marxism-Leninism, Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping Theory, the important thought of the “Three Represents,” the Scientific View of Development, and of course to Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era. Article 4 states the association’s commitment to “adhering to the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party,” as well as ensuring the operation of a Party organization and related activities within the association.

But neither is this, as some might imagine, a self-governing organization making commitments in principle to the tenets of CCP rule. The leadership structure of the CPAA ensures that it can be readily operationalized as a front to control the performance industry. In Article 5, we finally see clearly how the CPAA plugs into the government bureaucracy, despite its pretense of being a non-profit social organization. The language subjects the CPAA to the “oversight and control” of its sponsoring institution (业务主管单位), the Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

And what about the association’s leadership? Should we expect it to be led by active cultural performers and entrepreneurs — perhaps even a comedian or two? Who is Association President Liu Kezhi (刘克智)?

No bio is given for Liu Kezhi on the association’s website, but he is easy enough to track down. In fact, he is a top official in the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, and we can find him involved in a range of issues, including dealing with stranded foreign tourists at the start of the pandemic in February 2020 and conveying safety procedures that year for Dragon Boat Festival celebrations.

Liu Kezhi has even dealt frequently over the past two decades with issues concerning tourism between China and Taiwan. He appeared during a 2006 press conference held by the Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council, for example, to address cross-strait tourism. And 10 years later, as 26 Chinese tourists in Taiwan died when their chartered bus caught fire, Liu Kezhi was quoted in an official Xinhua news release expressing his “strong discontent” (强烈不满) with how Taiwan handled the incident. It was Liu Kezhi who “demanded that Taiwan must thoroughly investigate the cause of the accident.”

But there is a final, revealing, aspect to the Taiwan story that relates to the broader question of China’s operationalizing of ostensibly independent associations.

At the time of the 2016 tourism bus fire, Liu Kezhi had a government position as Director of the Department of Hong Kong-Macau-Taiwan Tourism Affairs at China’s National Tourism Administration. Why, then, would he be identified in official press reports as “Secretary-General Liu Kezhi” (秘书长刘克智)?

Well, at the time, you see, Liu Kezhi was also the number-one man at the Association for Tourism Exchange Across the Taiwan Straits (海峡两岸旅游交流协会). It will not surprise you to learn that the Association for Tourism Exchange Across the Taiwan Straits is a “non-profit organization” — or that it has offices in Taipei and Kaohsiung.

China has watchful eyes on every stage.