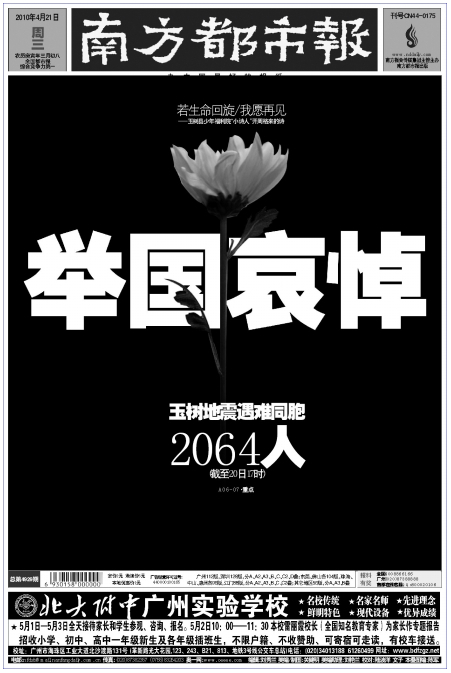

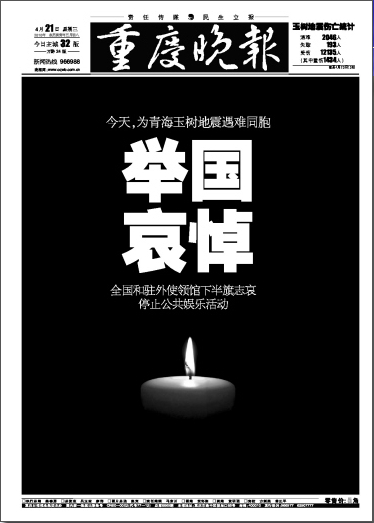

APRIL 21, 2010

Disaster relief should not by hyped

By Hu Yong (CMP fellow, professor at Peking University)

Disaster causes us all to feel that we live in an entirely different world. In the face of disaster, we all feel we must do something. In the aftermath of the May 12, 2008, earthquake in Sichuan, China’s open humanitarian attitude, courage and determination won the respect of the world. Now, once again, the earthquake in Yushu has stirred people’s hearts. The evening charity event on China Central Television on April 20 raised a total of 2.17 billion yuan, surpassing the 1.5 billion yuan taken in during the 2008 event that followed the Sichuan quake.

This show of broad concern is certainly moving. But we can also glean from these disaster relief efforts a taste of just how things have changed.

First of all, the attitude of those people and enterprises making donations has been “mixed with sand” (掺了沙子), so to speak. If you look carefully, you can see that some companies seem less attentive to the plight of those affected by the disaster than they are mindful of the opportunity to do a bit of public relations.

I use this word “seem” because there is no way to know whether they are genuine or not. But we saw with the Sichuan earthquake that it was the donors with star power that dominated the television lens, and no one was interested in other places. This time, companies doing their bit for the disaster relief effort are making a point of employing smart business strategies to demonstrate their “selfish” regard for the victims.

Next, in both disaster relief efforts, we saw the media making up donation scorecards, thereby putting a lot of pressure on companies. The amount of money companies put up for relief efforts has become a test of how much they are willing to give back to society.

These scorecards are updated daily and always changing, demanding the attention of anyone who cares about the donation effort. Who’s given more, and who’s given less. Who has stepped up in the rankings, and who has come down. These have become a focus of our attention.

We should understand that if we treat donors differently according to “who’s given more and who’s given less,” this will inevitably do harm to the sense of care and solicitude that donors feel. If these rankings continue to spoil the media with selfishness, the danger is that these “public instruments” will degenerate into snobbish instruments “forcing charity” on others.

As for “forcing charity,” Web users have a lot to answer for themselves. In the face of large-scale disasters, people naturally find it hard to keep cool heads — there’s nothing remiss about that. But there are times when we see emerge a kind of “tyranny of the majority.” In the wake of the May 12, 2008, Sichuan earthquake, the Chinese public went on a moral crusade, which we saw in the so-called “Donation Gate” involving China Vanke, which was seen as having donated too little, while Wanglaoji Pharmaceutical was praised for its generosity. The prevailing ethic throughout all of this was force and pressure.

Whether or not public figures donate money, and how much, has been put under the spotlight. Yao Ming, Zhang Ziyi and other full-fledged stars have all been subjected to a game by which we decide their hero status on the basis of how much they donate.

In the midst of the Yushu relief effort, this game has once again prepossessed Internet users in China. Who is giving more — private enterprises or state-owned enterprises? Chinese companies or international ones? Why aren’t industry monopolies giving more money? And these rough-handed property development companies of ours — what are they up to? The stars, the rich, the prominent — where do they stand?

This whole process exposes our tendency as a people to set moral benchmarks too high. It’s not bad for a person to act as a selfless sage, but we cannot point to sainthood as the basic standard to which all people must adhere.

The end result of setting such impossible standards is not the general improvement of society, but rather greater hypocrisy and repression. This is a lesson the Cultural Revolution has already taught us.

There are a few distinctions we need to be clear about. First, social responsibility and charity are not the same thing. In the midst of disaster, we’ve seen many companies making donations, and that is their social responsibility. Bearing an appropriate degree of social responsibility is a basic bottom line for any company’s survival. But we have to separate this social responsibility from charity.

When foreign business owners make contributions to a cause, their means of doing so differs clearly from what we see in China. When they the amount of their donation, they make clear whether it is made in the name of a foundation (set up by the owner, with private funds), privately or in the name of the company. in the first two cases, this can be referred to as charity.

By contrast, the vast majority of mainland companies are announcing the amounts of corporate donations. As I understand it, some even announce combined amounts comprising monies donated by the company itself and donations contributed from individual employees. Setting aside the contributions from employees, these corporate donations can be construed as acts of social responsibility. They are meant to make a favorable public impression, and the companies can count on social returns — although I would encourage them not to focus overly on what they get in return. Charity, on the other hand, arises out of my own personal moral convictions, and it cannot be done out of consideration for what I might get in return — lest it become hypocrisy.

Secondly, relief efforts made in good faith must not be subject to hype. To those companies who take part in the relief effort principally out of consideration for positive publicity, we must ask: in a normal market environment, companies are for-profit entities, but in the event of a disaster, can we not for a moment suspend market rules?

Third, donations should be made not out of duress exercised with enmity against those who have, but should instead be an act of gratitude. Disaster relief donations should come from a willingness to help. What we need from everyone at such a time as this is earnestness and care, regardless of how big or small a company is, or how rich or poor a person is.

As for those of us individuals who donate, we can make concrete calculations about how much material help we have provided to the victims of this disaster. But we cannot possibly estimate the effect the strength and spirit of those affected by the disaster has had on us. So perhaps it is more appropriate to talk not about what we have given, but about what we have received.

This article originally appeared in Chinese at Southern Metropolis Daily.