A wide-ranging new law to “enhance patriotic education” has come before China’s top legislative body, offering a new means to tighten ideological controls both online and beyond the country’s borders. Despite its emphasis on “promoting the spirit of patriotism,” the text of the law makes clear that the broader goal is to legislate love and devotion to the Chinese Communist Party and the top leadership.

“Patriotic education adheres to the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party,” the text reads, adding that it “integrates love for the country, love for the Party, and the love of socialism.”

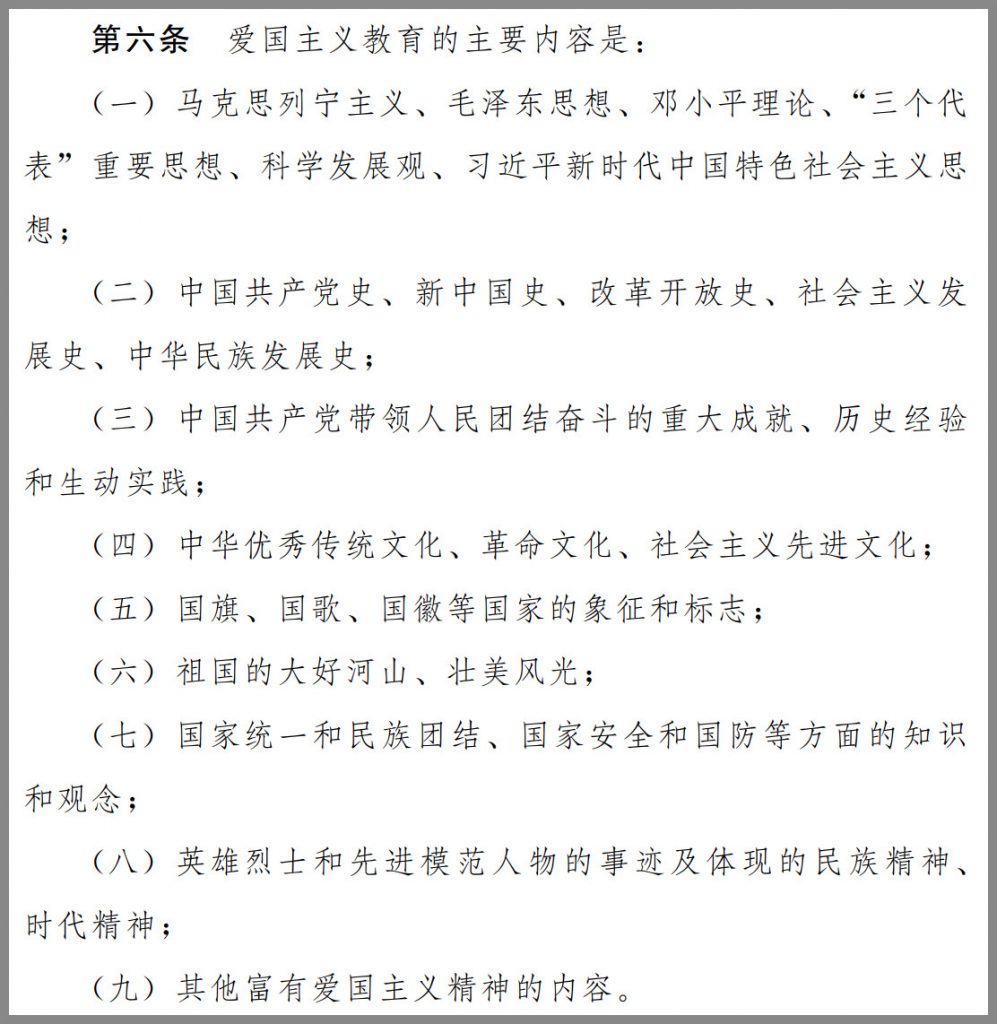

Submitted for review this week to the National People’s Congress Standing Committee, the draft bill lays out nine “main content” points of patriotic education. Six of these are explicitly political: they cover Marxism; Maoism; the theories of Xi Jinping; the leadership, achievements, and history of the CCP; revolutionary and socialist culture; national unity; and revolutionary martyrs.

In keeping with Xi Jinping’s rhetorical appeals to “Chinese civilization” to legitimize his growing power, “cultural traditions” like the Lunar New Year, Qingming, and the Dragon Boat Festival are identified as vehicles to promote patriotism. No cultural or political values beyond upholding CCP rule are clearly identified, however.

Closing articles in the draft lay out a litany of offenses that range from “undermining the dignity” of the national anthem, flag, and emblems to “denying the deeds of national heroes” and “denying acts of aggression” by foreign countries.

Departments of education, press and publication, film and broadcasting, culture and tourism are expected to “promptly stop and eliminate the impacts” of any violation, then “impose punishments” on violators whether or not they constitute criminal behavior.

In spirit, the draft bill reads like a return to the Patriotic Education Movements of the 1990s — a conservative backlash to the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests that stoked “national humiliation” resentments and patriotism to restore the CCP’s damaged legitimacy in the wake of its bloody crackdown on the protestors and its move away from Communist orthodoxy in favor of market reforms.

In scope, however, it adds significantly to both the technologies and jurisdictions affected. It requires internet content and service providers — as well as broadcasters and publishers — to strengthen the creation and dissemination of patriotic content and to develop new platforms and products to actively promote patriotism online.

This requirement, which comes amid an ongoing crackdown to “clean up” online content and accounts that do not fully align with Xi’s ideology, is a mandate not just for the state-run media to actively promote Party-led patriotism, but for privately-run internet platforms also to demonstrate their obedience with related content and technology innovations.

Party Patriotism Beyond the PRC

Significantly, it is the first patriotic education bill that specifically targets Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, and overseas Chinese. Article 22 of the draft requires the state “take measures […] to strengthen identification with the country and China’s excellent traditional culture” on all four fronts, although how they will do so in Taiwan, which they have never controlled, remains unclear.

Wong Kam-leung, chairman of the pro-Beijing Hong Kong Federation of Education Workers, said yesterday that the Education Bureau in the special administrative region should guide students to safeguard socialism and the leadership of the Communist Party of China. (The federation’s pro-democracy counterpart, the older and larger Hong Kong Professional Teachers’ Union, was disbanded in 2021 following a coordinated smear campaign by the Education Bureau and Chinese state media.)

Hong Kong’s government met widespread public resistance when it tried to introduce a “moral and national education” curriculum in 2012. The student movement that rose up in opposition to what it called “brainwashing education” catapulted teenage activist Joshua Wong to international attention. That movement is seen as a precursor to the 2014 pro-democracy Umbrella Movement. Wong is now jailed and the major groups that comprised the Civil Alliance Against National Education — including Scholarism, the Civil Human Rights Front, and the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China — have all been dissolved in the national security law crackdown.

The draft law is a mandate not just for the state-run media to actively promote Party-led patriotism, but for privately-run internet platforms also to demonstrate their obedience with related content and technology innovations.

When passed, the law will not immediately apply to Hong Kong; however, pro-Beijing legislators have pointed out that Article 18 of the city’s Basic Law empowered the National People’s Congress Standing Committee to directly apply national-level laws by adding them to Annex III of the law. This was the mechanism used in 2020 to push through the national security law which has decimated Hong Kong’s once-vibrant civil society. With Hong Kong’s Legislative Council purged of all opposition lawmakers, it offers a convenient constitutional backdoor to enact direct rule by Beijing.

The law could also have global implications. Even those far beyond China’s real or claimed borders are included in the law, with the same article mandating protection of “the rights and interests” of overseas Chinese and the “providing of services to enhance their patriotism and promote patriotic traditions.” At a time when Chinese communities are increasingly viewed with scrutiny as potential agents of the CCP abroad, such moves to tighten and enforce ideological controls on overseas Chinese may in fact prove detrimental to their “rights and interests.”