Headlines and Hashtags

A Law to Protect China’s Feelings

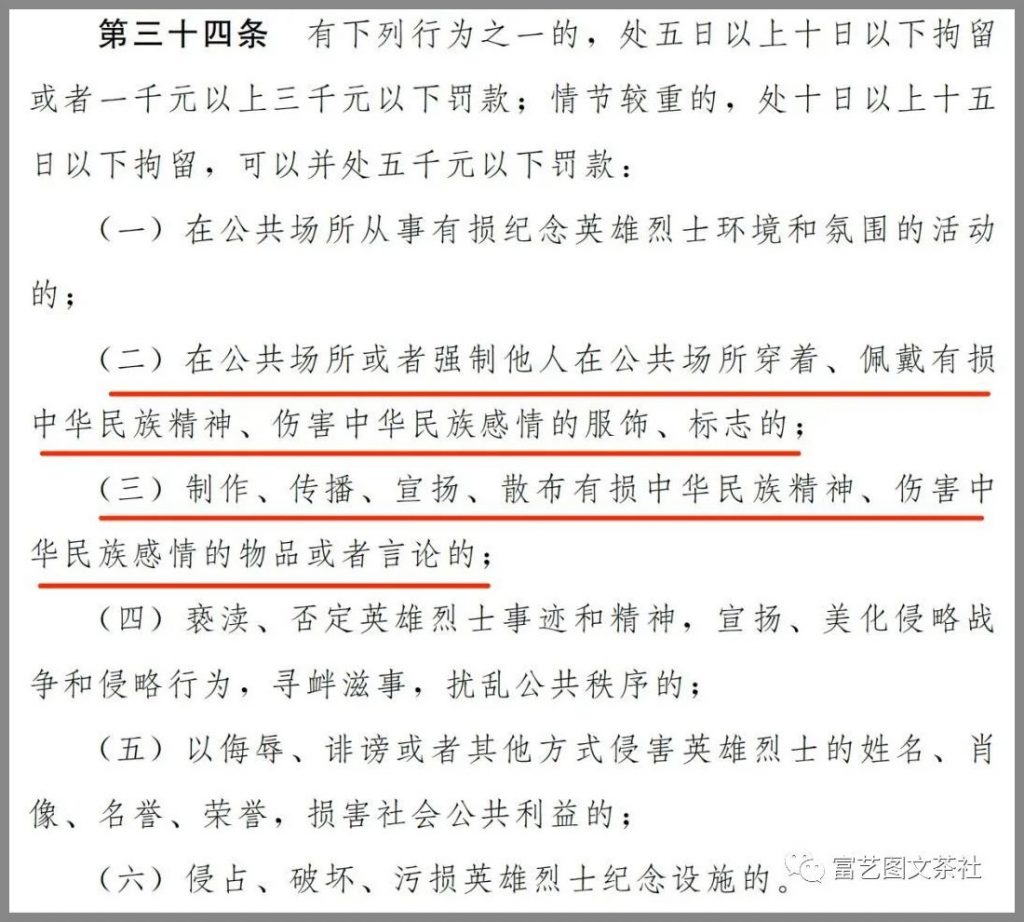

China’s top legislative body has proposed an amendment to a 2005 law that lays out specific punishments for violations that disturb public order. The changes would outlaw dress or speech that is “detrimental to the spirit of the Chinese nation or hurts the feelings of the Chinese nation.” Running afoul of this new stipulation could lead to 15 days in police detention or fines of up to 5,000 renminbi (680 dollars).

What does it mean to hurt the feelings of the Chinese nation? Many Chinese are asking exactly that question. Opened to public comment for 30 days, the draft amendment to the Public Security Administration Punishments Law has drawn a torrent of criticism. Public intellectuals, influencers, and ordinary netizens have lined up across social media to lay broadsides into the new language.

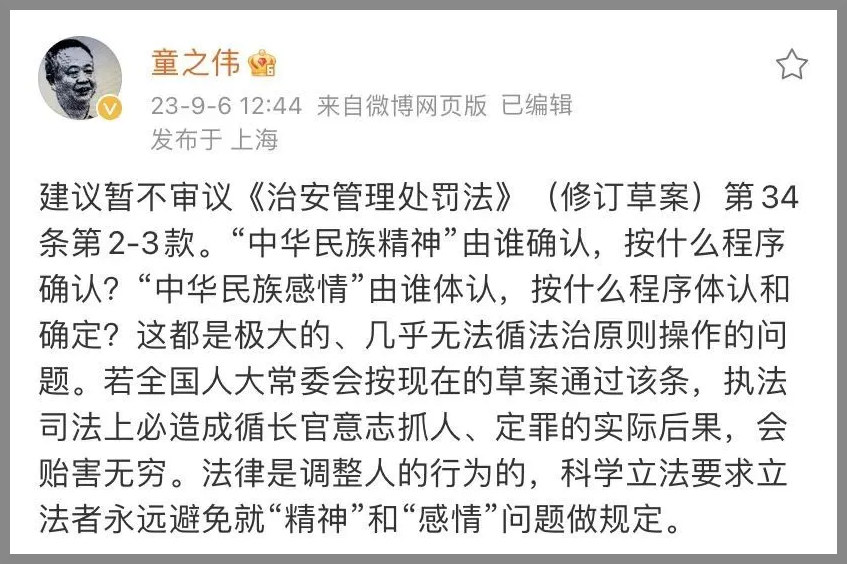

“Who decides what the spirit and feelings of the Chinese nation are?” asked Tong Zhiwei, a law professor in Shanghai.

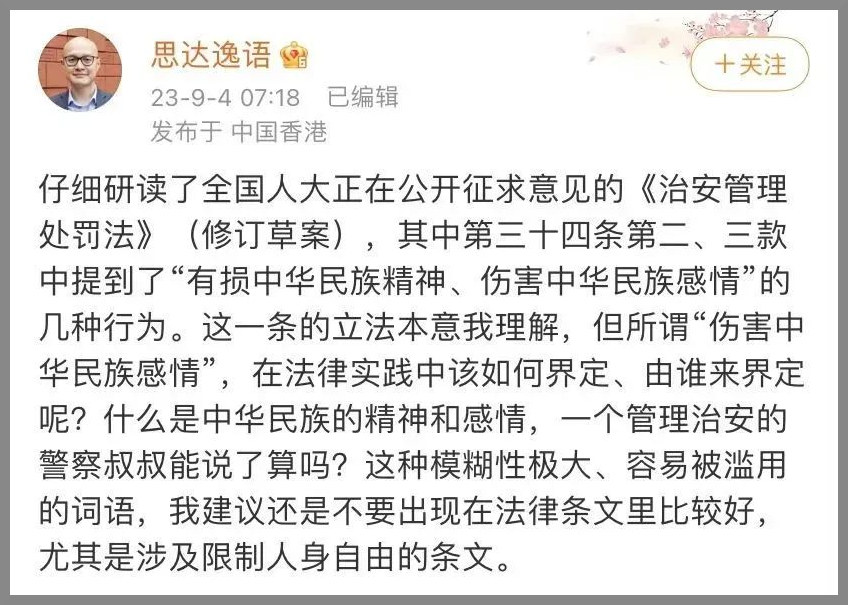

Professor Sida Liu at the University of Hong Kong called the wording of the provision “extremely vague” and questioned how it would be enforced: “Will it be up to individual police officers to decide what the spirit and feelings of the Chinese nation are?”

Lao Dongyan, a professor in the School of Law at Beijing’s prestigious Tsinghua University, wrote that the law threatens to fuel ultra-nationalist sentiments, further isolate China internationally, and damage relations between police and the public.

For many responding online, the prospect of arrests for wearing clothes that offend Beijing’s sensibilities — rationalized as those of the “Chinese nation” — brought to mind the August 2022 case of a Chinese woman detained in Suzhou for wearing a traditional Japanese kimono on the street.

One WeChat user teased that there was no need to stop with Japanese clothing. “China’s relations with a number of Western countries are not doing well now,” they wrote. “Will wearing a suit or jeans hurt the feelings of the Chinese nation?”

Another post predicted that, if the amendment came into effect, it might be advisable for people just to wear the drab tunic suits associated with Chinese Communism in the 1950s, which drew some inspiration from the style of Joseph Stalin. “I am afraid we will have to think twice about what we wear when we go out on the streets in the future…. The safest thing, to avoid being fined or detained, will be for everyone to wear Mao suits.”

Even a sports news feed joined in on the ridicule. One post compared the recent poor showing of the Chinese national football team against Malaysia to Japan’s triumph over Germany, and asked: “If China and Japan face off and Japan beat us again, which side should the police arrest? Who is hurting the feelings of the Chinese nation: Team China, Team Japan, or perhaps the broadcaster?”

A New Feeling?

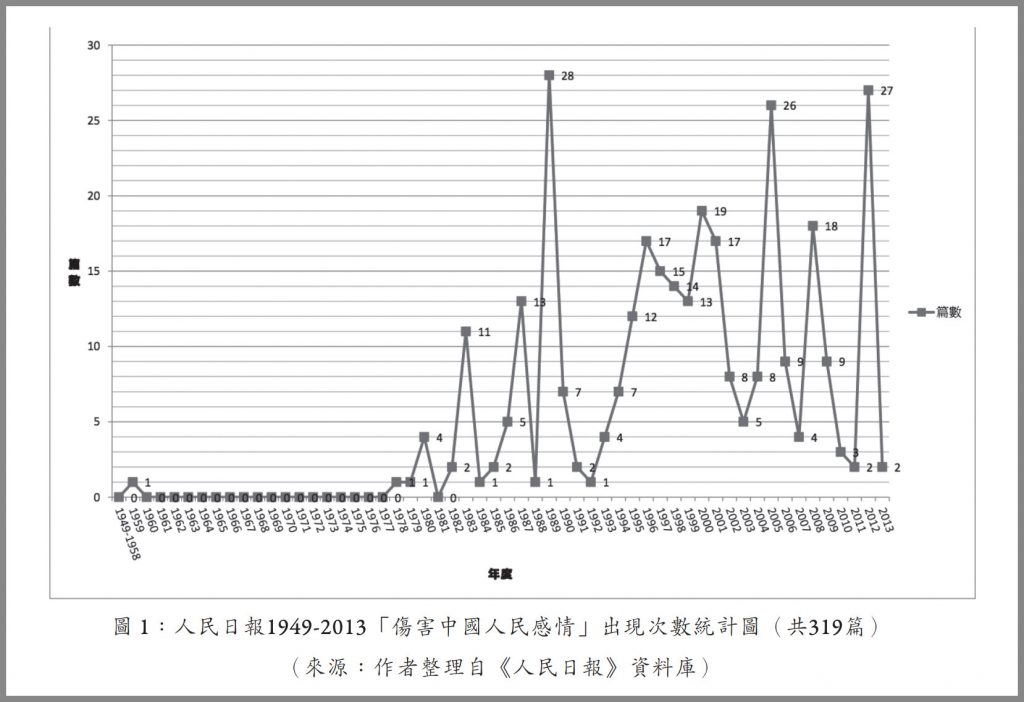

The reference to “hurt feelings” first emerged in 1959 in the pages of the Chinese Communist Party’s flagship People’s Daily newspaper, the full phrase being “hurting the feelings of the Chinese people” (伤害中国人民的感情). However, it was only after 1978 that the phrase was regularized, becoming a permanent feature of the Party’s political discourse.

The text of the “hurt feelings” draft amendment diverges from the longstanding CCP phrase, referring instead to lawbreakers who “hurt the feelings of the Chinese nation” (伤害中华民族的感情). Changes to the phrase reflect a recent development in the political discourse of the CCP.

The word “China” (中国), pointing in the original phrase to the People’s Republic of China, has been replaced with zhonghua (中华), a much broader notion that encompasses the idea of a grand Chinese civilization. Meanwhile, the reference to “the people” (人民), CCP political speak typically pointing to the general Chinese population under Communist rule, has been dropped in favor of the word minzu (民族), which suggests ethnic national identity rather than emphasizing the nation-state.

The new phrasing of the “hurt feelings” phrase has been around for several years, but has appeared only in unofficial media sources rather than in the People’s Daily or other state-run outlets. Appearing for what might be the first time in an official legal text, the new phrase broadens the accusation in keeping with Xi Jinping’s more recent legitimacy claims. It refers to ethnic Chinese around the world, rather than just within the country’s borders, and suggests that violations are a civilizational affront to all people of Chinese ethnicity.

The Chinese leadership has long had a conflicted relationship with Chinese nationalism as it bubbles up from below — as, for example, in the case of the anti-Japanese protests that rocked Chinese cities in 2012. That year, Chinese citizens initiated hundreds of protests to oppose Japan’s territorial claim to the Senkaku Islands, which China refers to as the “Diaoyu.” In response, fearing the protests might get out of hand, local authorities sought through various means to restrain and contain them.

The public outcry this month over the proposed amendment to the Public Security Administration Punishments Law suggests the relationship between the state and the public on nationalist emotion has now been turned on its head. The people are struggling to reign in the out-of-hand nationalism of their government.