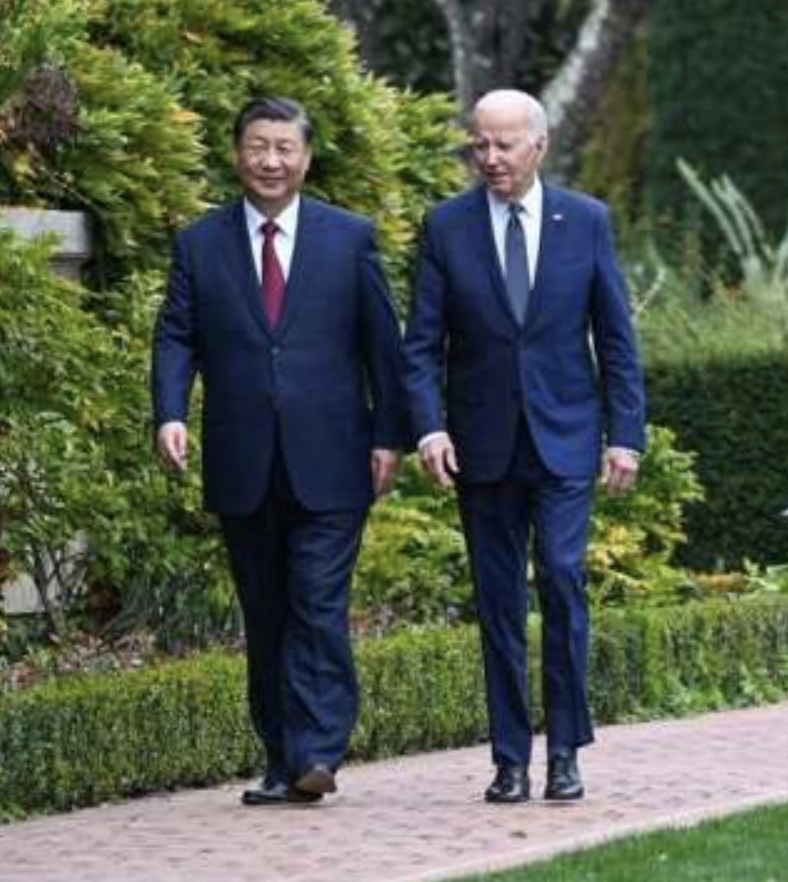

Few words rile up Beijing and China’s state-controlled media like “dictator” (独裁者). When US President Joe Biden said in November 2023 that he had not changed his view that his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, is effectively a dictator, it threatened to upturn the gains from the leaders’ long-anticipated summit days earlier.

The remark sparked an immediate backlash from Beijing, with a spokesperson for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs calling it “extremely incorrect and irresponsible political manipulation, which China resolutely opposes.” And this wasn’t the first time this back-and-forth had played out. Back in June, other remarks from Biden comparing Xi to dictators earned a similar rebuke.

Readers who have been following Xi’s consolidation of personal power over the past decade may be taken aback by the ferocity of this response. From eliminating constitutional term limits to sidelining all potential rivals and rolling out a cult of personality unseen for decades, it would seem obvious that Xi is taking concrete steps to amass power in his personal leadership.

And isn’t that the definition of a dictator?

The point of tension lies in how the China Communist Party (CCP) leadership wishes to characterize its dominance of the country’s political system, which even today its constitution identifies as a “dictatorship of the proletariat.” The Party wants to have its cake and eat it too: to be all-powerful but also to be seen as representative; to be feared and to be loved — avowedly — throughout the world.

Understanding these sensitivities surrounding “dictators” in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) requires a brief look back at the country’s continuum of revolutions in the 20th century.

Eye of the Beholder

When the Republic of China was established on January 1, 1912, thousands of years of dictatorial rule by China’s emperors were ended. And despite slipping back into eras of effective one-man rule since then, both major parties vying to rule China — the CCP and the nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) — see themselves as the rightful inheritors of this tradition, the slayers of dictators and liberators of their benighted countrymen.

KMT supporters called Mao Zedong — along with national enemies Joseph Stalin, Adolf Hitler, and Tōjō Hideki — a dictator. Throughout their great rivalry, the CCP denounced KMT Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek as a dictator as well. And the habit is proving hard to kick: long after Mao’s triumph in 1949, the death of Chiang in 1975, and the democratization of Taiwan in the 1990s, accusations of dictatorial rule on Taiwan are still being fired across the strait — despite becoming increasingly far-fetched.

Beijing, which now favors its erstwhile rivals in the KMT, doesn’t call Chiang a dictator so much. Instead, they direct the barb at elected leaders from the more Taiwan-focused Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). President Tsai Ing-wen of the DPP, who won a landslide victory in 2020 and will step down in 2024 after serving the constitutional limit of two terms in office, is a “dictator” and “power monster” who is “constructing a near-perfect dictatorship” and “devouring Taiwan’s democracy,” according to Overseas Net, an outlet aimed at diasporic Chinese operated by the CCP’s flagship People’s Daily newspaper.

Democrats in Hong Kong have also been tarred with the same brush. In 2021, as authorities in Hong Kong used the Beijing-imposed national security law to jail nearly every prominent member of the political opposition, a microblogging account amplified by official media said pro-democracy protestors were the territory’s “real dictators” due to their appeals for sanctions on the authorities imprisoning them.

Beyond its real and claimed borders, the PRC is also ready to bat for “dictators” they regard as onside. In a poorly-aged article published two months before Russia invaded Ukraine, the People’s Daily accused Western media of “smearing” Vladimir Putin and Belarussian strongman Alexander Lukashenko as dictators, “wantonly hyping” the unsubstantiated rumor that Moscow was preparing to invade its neighbor to the west.

Like the myth that the CCP ended class distinction in China, the myth that it ended thousands of years of dictatorship is foundational to regime legitimacy. No matter how long Xi stays in power and how much authority he accumulates in his own two hands, he will always deny the characterization of himself as a dictator. Calling him that wouldn’t just be “extremely incorrect and irresponsible” — it could even make you “the real dictator.”

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

The CMP Dictionary

C

D

F

G

M

N

P

S

- Scaling the Wall

- Science

- Second-Generation Reds

- Security

- Seeking Progress in Stability

- Seeking Truth From Facts

- Self-Revolution

- Seven Bottom Lines

- Six Adheres

- Smart Governance

- Sneaky Visit

- So-Called

- Socialite

- Soft Resistance

- Soul and Root

- Soundless Saturation / Quietly Nourishing

- Sovereignty

- Speaking Politics

- Streamlining Services

- Strong Cyber Power