The years 2013 and 2014 were a pivotal time in the formation of the Chinese leadership’s approach to restricting political speech on social media platforms such as Sina’s Weibo and Tencent’s WeChat (微信). Over the preceding several years, the Chinese Communist Party had struggled to maintain control over public opinion in a new information world increasingly dominated by internet chatter.

Just ahead of the Beijing Olympic Games in 2008, President Hu Jintao (胡锦涛) had outlined a new policy under the notion of “public opinion channeling” (舆论引导) — his hope being that state media could “seize the initiative” and “actively set the agenda” by reporting and dominating sudden-breaking news stories before they could explode online. But these plans were undermined dramatically by the emergence of social media platforms like Weibo and WeChat that super-fueled communication in real time, and created a new generation of microblog influencers with audiences stretching into the millions.

Reigning in the Influencers

In January 2013, PRC officials began informal attempts to exert pressure on popular social media figures by pulling them in for interviews (commonly referred to in Chinese as “being asked to tea”). Some of those subjected to government coercion included businessman Ren Zhiqiang (任志强) and Taiwanese artist Yi Nengjing (伊能静).

On the evening of January 9, 2013, former president of Google China Kai-fu Lee posted the following on his Sina Weibo: “This tea is hard to swallow!” (好难喝的茶!). Several minutes later, Lee posted the following, hinting at the new restrictions he would be subjected to online: “From now on, [I will] only discuss East, West, and North, and only discuss Monday through Friday” (从现在开始,只谈东西北方,只谈周一到周五).

These were the earliest rumblings of what would soon become an earthquake for online influencers like Lee, who were known as “Big V” (大V) for their verified accounts on Weibo and other platforms, and who had personal audiences running into the millions and even tens of millions.

In a response to the outspoken real estate tycoon Ren Zhiqiang (任志强), who had gathered well over 30 million followers, and who had cryptically posted a message reading, “The first time” (第一次吧), Lee gave the following response on January 10, 2013:

There’s always a first time for everything. Why not approach it wholeheartedly, not letting them vex you. You needn’t ask me what is false and what is true, as I would that your doubts would be alleviated. For everything you do there is always the first time. May you be clear about what is right and what is wrong.

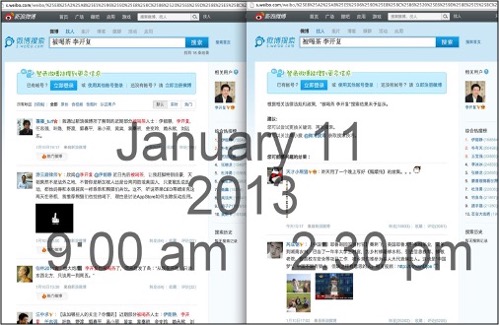

In these early stages of the campaign against China’s “Big Vs,” such actions were highly sensitive. As word spread of the intimidation of social media influencers by the authorities, Sina Weibo began censoring related phrases, including “Asked to Tea Lee Kai-fu” (被喝茶 李开复), “Asked to Tea Ren Zhiqiang” (被喝茶 任志强), and “Asked to Tea Yi Nengjing” (被喝茶 伊能静).

On April 10, 2013, the CCP leadership officially announced its plans for the authorities to reign in social media influencers in an editorial in the official Red Flag Journal (红旗文稿), published by the Party’s flagship magazine Seeking Truth (求是). Called “Target the Two Venues of Public Discourse, Solidify the Positive Energy of Society,” the editorial was authored by Ren Xianliang (任贤良) who, at the time of publication, was acting vice-minister of Shaanxi province’s propaganda department — and would soon be appointed deputy director of the State Council Information Office (SCIO), the body with primary control over the internet in China at that time. Ren words, which lay out that CCP’s position quite clearly, are worth quoting at length:

The abrupt rise of the Internet and other new media, especially the appearance of blogs and weibos and other forms of personal media, has in fact undermined policies that banned private media and prohibited cross-border oversight. Certain VIP weibo users frequently have tens, if not hundreds, of thousands, even millions, of followers, and go so far as to launch micro-magazines and micro-television channels. . . . .

When it comes to control, it is necessary to boldly confront all obstacles, even those powerful media outlets, famous web sites, bloggers, and micro-bloggers. Warn those who need warning, ban those who need banning, and silence those who need silencing. As soon as there is any violation of law, rules, or discipline, resolutely handle it in accordance with the law, and show no mercy. It is only by using the law to manage new media formats, including the Internet, in the same manner as is done with real-world society, that we can turn it to our own ends and not be subject to external threats. . . . .

Online “opinion leaders” represent the aspirations of a sizable portion of the crowd. They are the focus of much public attention, and hold great sway over users’ moods and online opinion. Administrative agencies must adopt many different methods to transform, foster, and cultivate “opinion leaders” who understand, approve of, and praise the general and specific policies of the Party and the government, and use them to influence Internet users and guide public opinion.

The day after the Red Flag Journal article went online, Southern Metropolis Daily (南方都市报), a commercial tabloid published under Guangdong’s Party-backed Nanfang Daily newspaper, turned the focus of the public toward Ren’s commentary, which might otherwise have been lost in the tide of official-speak. The article’s headline made the intentions of the leadership crystal clear: “Shaanxi Official: Some Online Discourse is Being Manipulated, When It Comes to the Big V’s On Weibo, Silence Those Who Need Silencing” (陕西官员:一些网络舆论被操纵 微博大V该关就关).

As authorities moved to contain the negative fallout, the Southern Metropolis Daily rundown of Ren’s editorial was quickly removed from the internet.

Rumors and Responsibilities

Over the next several months, state media paved the way for a broader campaign against online influencers by hyping rumors and immoral conduct on the internet as a social ill that required government intervention.

In August 2013, the Global Times, a nationalistic tabloid published under the CCP’s official People’s Daily newspaper, ran an article that chided “celebrity microbloggers” for their naivety in assuming that they enjoyed a “political discourse power” that could not be restricted. “Discourse power is a special public right, and political discourse power is especially sensitive,” said the article, adding that Weibo celebrities “need to be capable of properly using their discourse power, rather than abusing it.”

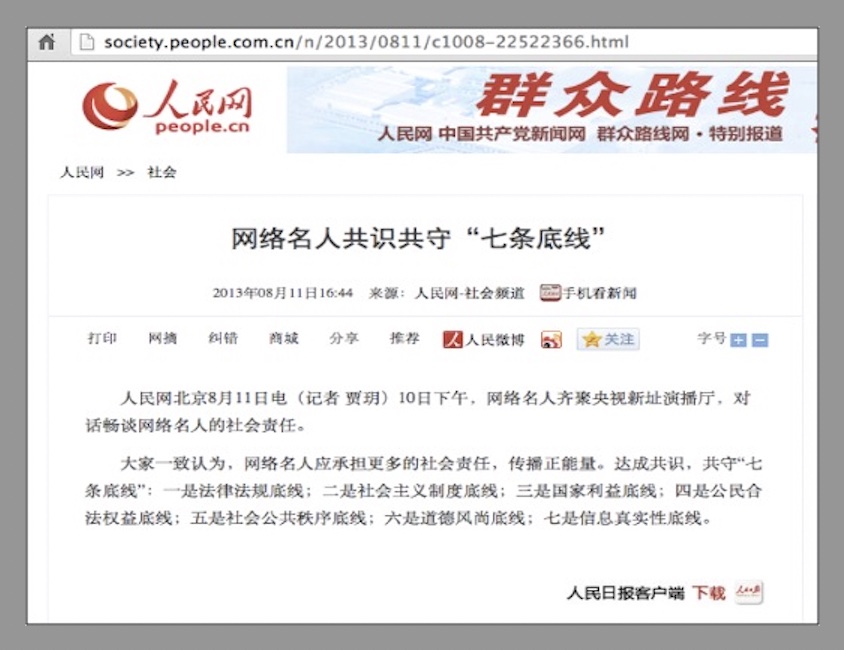

It is in the context of the crackdown on Big Vs, accelerating in August 2013, that we find one of the earliest mentions of the “Seven Bottom Lines,” which appears to have come in a report posted to People’s Daily Online on August 11, 2013.

According to that report, “well-known online personalities” had gathered on August 10, 2013, at the headquarters of the state-run broadcaster China Central Television (CCTV) in Beijing, and had reached an agreement on seven bottom lines to be conscientiously observed. These included:

- Laws and Regulations

- The Socialist System

- The National Interest

- Citizens’ Legal Rights and Interests

- Social Order

- Moral Norms

- Factual Information

That report provided no details as to what those terms meant, but three days later a government-run website in Sichuan province published an article entitled “The Seven Bottom Lines That Every Internet User Should Observe” (七条底线,全体网民应该共守). The article placed “the nation” and the “national interest” above all considerations, saying that China must “forge a patriotic online culture.” The implication was the need for all users to mind the political bottom line, which the piece made clear was the socialism system: “This is our fundamental institution, a bottom line we cannot neglect. Whether in real life on the internet, we eat and live socialism. We cannot undermine ourselves.”

Several days later on August 16, a spate of reports from state media outlets made clear that the the notion of the “Seven Bottom Lines” was the brainchild of Lu Wei (鲁炜), a deputy minister in the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department who just three months earlier had been appointed as the first director of the newly-created Cyberspace Administration of China.

According to these reports, Lu had chaired the August 10 meeting at CCTV, where he had announced that “internet celebrities should take on more social responsibilities, spread positive energy, and collectively abide by the ‘seven bottom lines.’” The phrase rapidly developed from a fledgling phrase into a full-fledged official term, or tifa (提法). In September 2013, a special section at People’s Daily Online was created to aggregate articles and reports on the phrase, and how it was being used to enforce the leadership’s norms on social media.

Through that fall and into 2014, the “Seven Bottom Lines” was the bludgeon used to bring social media platforms to heel. By November 13, 2013, the Beijing Youth Daily, an official newspaper published under the Beijing branch of the Chinese Communist Youth League, reported that at least 100,000 Weibo accounts had been “handled” (处理) using the policy.

Ultimately, however, the leadership could not bring online influencers under control through informal coercion and propaganda campaigns alone. So on August 7, 2014, nearly one year after the campaign against China’s Big Vs had gone into full swing, the CAC issued a document called Interim Rules on the Development and Administration of Instant Messaging Tools and Public Information Services.

The Rules applied to anyone “employing instant messaging tools as public information services,” but their main target was so-called “public accounts,” or gonghao (公号)– accounts on Tencent’s social media platform that unlike private messages could be shared and viewed by the general public. Accounts focused on discussing history and current affairs were a particular target of government crackdowns under these new Rules.

One of the ways the Rules acted to restrict users ability to establish public accounts was to impose administrative hurdles. Specifically, Tencent was required to verify the identity of anyone applying to operate a public account, and register all those who were verified with “a government agency responsible for Internet information content.” The Rules also ordered Tencent to require their users to enter into terms of service whereby each user would commit to abide by the “Seven Bottom Lines.” The Rules did not define what the “Seven Bottom Lines” were, and the term had not appeared in any previous PRC law or regulation. The government simply incorporated-by-reference a propaganda phrase into its official administrative rulemaking.

The government had apparently anticipated that there would objections to its incorporation of the “Seven Bottom Lines.” Soon after the Rules were released, the official Xinhua News Agency came out with a list of talking points called “Do the Rules Restrict Speech?” The cited a government spokesperson walking through such objections:

The “Weixin Ten Articles” are relatively strict when it comes to publicly posting information, especially current events and political news. But with respect to ordinary users, it only requires they obey the “Seven Bottom Lines,” and they will enjoy ample freedom of speech based on these “seven bottom lines.”

The scope of what constituted “ample freedom of speech” under these “Seven Bottom Lines” was made clear a couple of months later, when social media outlets censored an online influencer for openly criticizing a pro-CCP blogger named Zhou Xiaoping (周小平) who had been singled out for praise by CCP Chairman Xi Jinping at a gathering on cultural policy.

The online influencer in question was Fang Zhouzi (方舟子), who had made a post to his Baidu Baijia blog entitled “Zhou Xiaoping Sleepwalks Through America” (周小平梦游美利坚). In his blog post, Fang singled out factual inaccuracies in a Zhou Xiaoping essay published in the CCP journal Party Building (党建) that was critical of the United States.

William Farris

The CMP Dictionary

C

D

F

G

M

N

P

S

- Scaling the Wall

- Science

- Second-Generation Reds

- Security

- Seeking Progress in Stability

- Seeking Truth From Facts

- Self-Revolution

- Seven Bottom Lines

- Six Adheres

- Smart Governance

- Sneaky Visit

- So-Called

- Socialite

- Soft Resistance

- Soul and Root

- Soundless Saturation / Quietly Nourishing

- Sovereignty

- Speaking Politics

- Streamlining Services

- Strong Cyber Power