In other parts of the world, getting elected to lead one’s local press group is a cause of celebration — a sign that a journalist has become a pillar of the professional community, esteemed and trusted by their colleagues. But for Selina Cheng, it was a cause for concern. The day after she was chosen by members of the Hong Kong Journalists Association to be their next chairperson, she told the China Media Project she was surprised not to have been immediately fired by her employer, the Wall Street Journal. When senior editors learned about her plan to stand on the eve of the election, her supervisor at the WSJ’s international desk in London told her to withdraw and quit the HKJA’s executive committee, where she had already served for three years.

The hostility Cheng faced from her workplace, however, only steeled her resolve to give back to the community. “Reporters in Hong Kong know their editors or employers don’t always have their backs,” she said. “That’s why the JA is so important. We want other journalists to know we’re here for them.”

The relief, however, would not last long. Less than a month later, Cheng was fired by the Journal, with World Coverage Chief Gordon Fairclough appearing at the Hong Kong bureau to deliver her termination notice in person. The weeks in between, she realized, were merely to square things with legal and prepare the paperwork — and the HKJA’s first battle to defend press freedom under her leadership would be her own.

Fighting on Two Fronts

The Journal’s decision sent shockwaves through Hong Kong, where press freedom has been pushed to a cliff-edge by an ever-widening national security crackdown that has both netted reporters and media executives and forced some of the city’s most popular news outlets to shut down. But the most concerning part of the story might in fact be how unsurprising it was.

Rumors had already been swirling that international newsrooms were dead-set against employees getting too involved in the body, which had become the target of a government and state media smear campaign. The China Media Project spoke with three newly elected members of the HKJA board, as well as an outgoing leader of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China, which has faced similar pressures. All asked to remain anonymous, fearing reprisals from their employers, but confirmed that the Journal is not alone: the biggest names in Hong Kong and China’s foreign press have been pressuring their employees to stand back and stay quiet, or face the repercussions. For the territory’s embattled journalists, defending the free press has become a fight on two fronts: against both an increasingly authoritarian government and their own employers, based in the West and nominally committed to liberal principles.

For Hong Kong’s embattled journalists, defending the free press has become a fight on two fronts: against both an increasingly authoritarian government and their own employers, based in the West and nominally committed to liberal principles.

As well as the Wall Street Journal, outlets cited included the BBC, CNN, and Bloomberg — newsrooms that, in at least one case, had staff join the HKJA en masse during the city’s mass anti-government protests in 2019, when HKJA press cards were seen as a defense against police hunting for “fake” or “black journalists” (黑記) they regarded as supporting the democracy movement. These organizations were apparently willing to benefit from the Association’s protections when they themselves were under threat, but are now reluctant to return the favor when the group — and local journalists as a whole — are in the firing line. As one new HKJA leader pointed out, these are also outlets that would never try to prevent their employees from joining similar press clubs in their home countries.

Their accounts are also backed up by Eric Wishart, former president of the city’s Foreign Correspondents’ Club and AFP’s standards and ethics editor. “I can attest to the fact that several international media organizations in Hong Kong have barred their journalists from standing for club president over the years,” he says. “I know of several good potential candidates who were told by their management that they could not run — that’s why the election for president is often uncontested due to a lack of candidates.”

International media are not alone in efforts to dissuade employees from joining the JA, however. Some local newspapers are taking a similar line — but they are split, unsurprisingly, along political lines. All staff at the independent, reader-funded Hong Kong Free Press, for example, are HKJA members. One HKFP staff member, reporter Hans Tse, sits on the executive committee and told the China Media Project that his employer did not interfere with his decision. Ming Pao (明報) and the Alibaba-owned South China Morning Post do not oppose staff joining the group, reporters say, but would prefer they not serve on the executive committee. The pro-Beijing Sing Tao (星島) and Oriental Daily (東方日報) newsgroups, meanwhile, may not hire reporters who are HKJA members.

Considering the climate of fear around taking up prominent positions in the HKJA, it is easy to see why freelance journalists — unbeholden to a single employer — have been more willing to step up recently. This year’s executive committee included two reporters for foreign media and a record three freelancers, among a total of eight members — a fact that has been weaponized by the Hong Kong government and its state-run media. Earlier this year, Secretary for Security Chris Tang suggested that the organization has become unrepresentative and illegitimate owing to the number of freelancers and foreign media employees standing for election. After the election, two newly elected board members immediately stepped down, including a reporter with the BBC who also faced opposition from his employers, according to others on the board. Another board member told us he feared stepping forward to serve on the body would be “career suicide.”

“Pressure on journalists comes in many forms,” Cheng says. “Not just high-profile cases like Stand News and Apple Daily but also small, even mundane incidents in the day-to-day.” She says it was “naive” to believe foreign editors who vowed they would close the local bureau before bowing to self-censorship. “We see now that even editors thousands of miles away, on different continents, are affected by deteriorating circumstances in Hong Kong.”

Crackdown Upon Crackdown

The main argument, according to Cheng, is that press freedom in Hong Kong is now seen as a “contentious,” even “anti-government” issue. Cheng has declined to conjecture about the Journal’s motivation for firing her, but another HKJA board member suggests it could be related to their reporters’ access to the Chinese mainland. Foreign media are subject to monthly communications with China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, they point out, where they are told whether their reporting has been appreciated by authorities or not. Increasingly concerned about access to mainland China, higher-ups in the foreign press are keen not to unnecessarily ruffle any feathers in Beijing.

But the HKJA is not just an advocacy group for press freedom — it is also a trade union representing the interests of its membership. “The advocacy side may have stood out more in recent years given the need to defend press freedom,” another HKJA board member told us, “but the JA has also been helping former Apple Daily staff regarding their labor rights as well.”

Looking ahead, they want the group to focus more on their union work — both to reach more potential members and bolster their profile and, they hope, avoid the government’s wrath: “I think, realistically, we should strengthen our capacity as a union, to connect with journalists who are not yet our members. I believe if we can convince them that JA is here to help, it will bring credibility and support to JA, and also I think the government may be less interested in us if we focus solely on union works — but that's only a guess.”

And it may, unfortunately, be an overly optimistic one. The government has not just been cracking down on advocacy groups in Hong Kong, but independent trade unions as well. Hundreds of unions have been dissolved or stopped operations since the start of the national security crackdown in June 2020, and numerous unionists have been arrested, incarcerated, or had bounties put on them. Two of the city’s biggest unions, the pro-democracy Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (HKCTU) and the politically liberal Hong Kong Professional Teachers' Union (HKPTU) were disbanded in 2021. Last year, police put a HK$1 million bounty on the head of former HKCTU leader Christopher Mung, now in exile in the United Kingdom.

The HKJA stands at the confluence of two concurrent crackdowns: one on the free press and one on organized labor. While the latter may be deemed less sensitive for now, it is far from a guarantee of insulation from the authorities.

Watchdog or Lapdog?

That is not to say that Hong Kong authorities have come down on all unions or press groups, however.

At the same time as the government has been beating down the HKJA, it has been lifting up the Hong Kong Federation of Journalists (香港新聞工作者聯會), an alternative press group formed by “patriotic” journalists on the eve of Hong Kong’s 1997 handover to the PRC. As the Hong Kong government prepared to introduce its own, locally legislated national security law known as Article 23 earlier this year, to supplement the one imposed by Beijing in 2020, it invited the HKFJ — and not the HKJA — to join its consultation process.

At the unveiling ceremony for HKFJ’s new office last year, located in the North Point neighborhood that has for decades hosted pro-Communist institutions, HKFJ Chairman Li Dahong (李大宏) said that the HKFJ “would not let down the honored guests” assembled for the occasion. Rather curiously for a press advocacy group, these included Lin Zhan (林枬), deputy director of the Cultural Affairs Department of the Central Government’s Liaison Office, and a special commissioner on the press from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) — the kinds of officials that professional media unions are often at loggerheads with.

As it happens, Li Dahong wears many crowns in Hong Kong. As well as chairing the HKFJ, he is the chairman and editor-in-chief of the Ta Kung Wen Wei Media Group, which combines the city’s two biggest state-run newspapers, the Ta Kung Pao and Wen Wei Po. He is also a delegate to the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (中國人民政治協商會議全國委員會), the CCP-led political advisory body. Li is a prominent representative, in other words, of a model of state-led journalism that doesn’t question political power but serves as its megaphone.

It’s a model well-understood to anyone familiar with the All-China Journalists Association (中華全國新聞工作者協會). The ACJA, as the China Media Project has covered in numerous pieces over the years, is not your typical industry organization. Even though it describes itself as “a national non-governmental organization” the ACJA in fact serves as an important layer for exercising the Chinese Communist Party’s control over news organizations and the country’s more than one million registered journalists, rewarding compliance with the CCP’s demands and punishing perceived failures.

Earlier this year, the HKFJ hosted a gala dinner where they were addressed by Hong Kong’s Chief Executive John Lee. As though channeling the spirit of official numerology, so common to the rarefied discourse of China’s ruling Communist Party, Lee laid out Three Goals for news media in the Special Administrative Region (SAR). First, “promote patriotism”; second, “tell good Hong Kong stories''; third, “act as a communication channel between the government and the people.” The same night also served as the launch ceremony for a new body in the ACJA’s mold: the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area Media Federation (粵港澳大灣區媒體聯盟).

Given the strong history of press freedom in Hong Kong, such unapologetic intrusion into the work of local media would have appalled many of the city’s famously dogged reporters. But for the event’s hosts, it was all par for the course. As HKFJ leader Li Dahong addressed the crowd, he said in a nod to one of Xi Jinping’s key propaganda phrases that this new mega-group would endeavor to “tell Greater Bay stories well,” and that it would share the HKFJ’s foundational mission “to support the SAR government.”

The charge to smear, discredit, and ultimately destroy the HKJA has been led by none other than Li Dahong’s Ta Kung Pao and Wen Wei Po. The two newspapers have dedicated reams of coverage to casting aspersions on the Association and its leadership. This includes accusations that the HKJA is an “anti-China” foreign force representing “Anglo-American” political interests, calls to disband the group immediately, and threats that members who do not “jump ship” before the HKJA sinks will “go down with it.”

This, at least, is one form of “journalism” local authorities can get behind.

War of Attrition

In the face of threats like that to even ordinary members, the HKJA is facing “an existential crisis with memberships in decline and the government crackdown,” an executive committee member tells us.

It’s a scenario grimly familiar to members of the Foreign Correspondents' Club of China. A former FCCC member told the China Media Project the club was “struggling” to find candidates for its board. And while the dwindling number of foreign correspondents in Beijing had definitely been a factor, it was not the only one.

Last year, two candidates for the FCCC board pulled out after authorities “called them in for tea” (a euphemism for police questioning and intimidation). This year, the nationalistic Global Times newspaper, part of the People’s Daily group, has published hit pieces targeting both the FCCC and the HKJA, and several would-be FCCC board members ultimately declined to stand, citing opposition from their employers. Board members who had intended to resign feared they would be forced to stay in their positions for another year just to keep the club functioning.

At the group’s annual general meeting on May 23, most of the event was spent “haranguing members about standing and preserving the club,” according to a member present — but to no avail. No one stepped up, although some remarked that they had not realized the situation was so dire. “Hopefully,” this FCCC member told us, “recruiting will be easier next year.”

In both cases, the endgame for central government authorities in Beijing and their proxies in Hong Kong seems to be the same: for these independent and often outspoken groups to either be squeezed out of existence or willingly transform into a compliant shadow of their former selves. That was the fate many ascribed to Hong Kong’s FCC after the club suddenly scrapped its annual Human Rights Press Awards in 2022, when the now-shuttered pro-democracy outlet Stand News had earned several honors. AFP’s Eric Wishart, however, who resigned from the FCC in protest over the awards’ cancellation, says that “the club has slowly rebuilt its reputation as an advocate for media freedom” under new leadership, issuing statements on various media freedom issues including Selina Cheng’s termination.

Noting that “different press groups around the region have had problems finding board members, people willing to step up,” Selina Cheng says she is worried her case could set “a negative precedent” if it goes unchallenged.

That’s why she has vowed to fight her dismissal in Hong Kong’s courts. According to the territory’s Employment Ordinance, every employee has the right “to be a member or an officer of a trade union.” During her termination, senior WSJ staff cited a potential conflict of interest between Cheng’s position at the HKJA and the outlet’s reporting. But Cheng — who covered the Chinese EV industry — says it is “very clear what they were trying to do with my termination” and she is confident the courts will protect her rights.

A Study in Contrasts

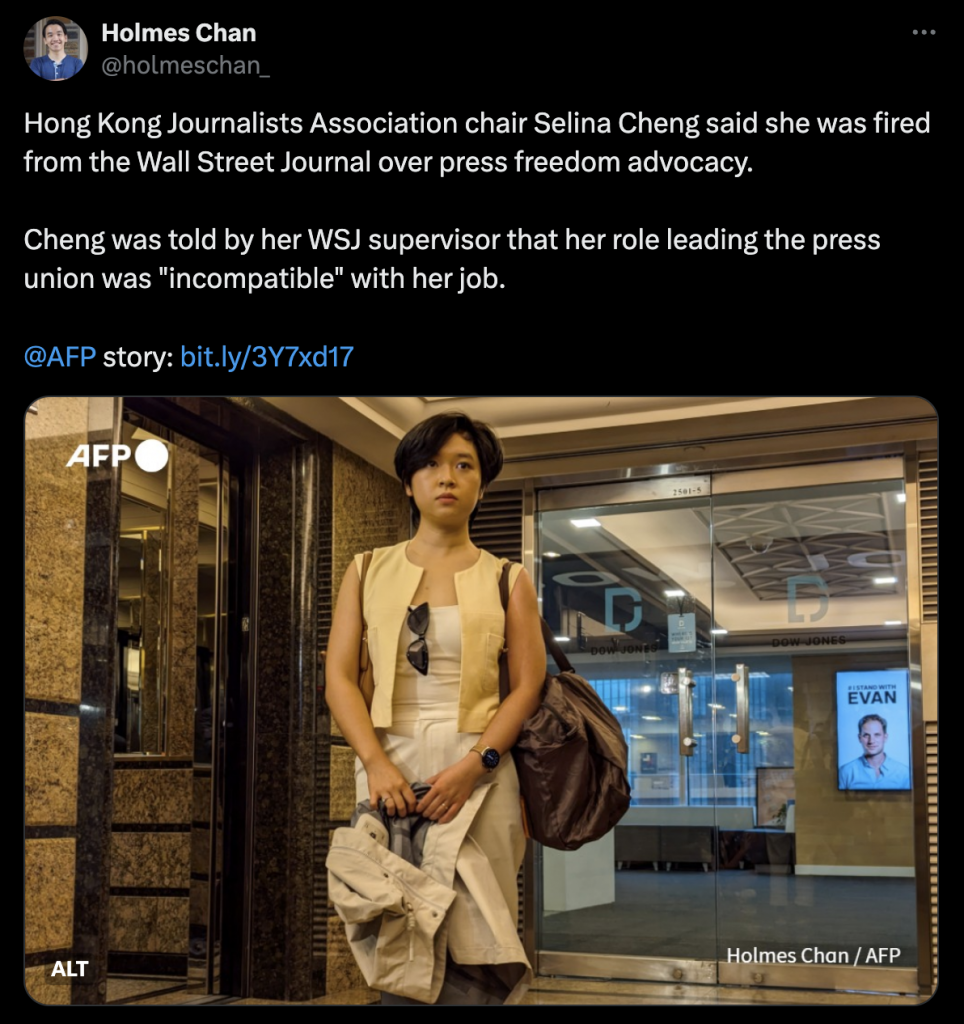

As Cheng stepped out of the WSJ office for the last time, AFP reporter Holmes Chan captured this remarkable image of her in the lift lobby, the bureau’s glass doors between her and a portrait of her erstwhile colleague Evan Gershkovich.

Since Gershkovich was detained in Russia last year and falsely accused of espionage, his employer has pushed hard for his release. Efforts by management, editors, and fellow reporters at the Journal to ensure that Gershkovich is not forgotten — which included shaving their heads in solidarity — have been a reassuring picture of how all journalists hope their colleagues will react should they face persecution for their reporting.

It’s also why Cheng says she was “deeply shocked” when the Journal demanded she not get involved in free-speech advocacy. Is that not, after all, exactly what the Journal itself is doing by advocating — rightly — for Gershkovich?

“Every country needs press freedom,” Cheng says, Hong Kong as well as Russia. And at a time when international organizations that paint themselves as champions of the free press seem to disagree on this point, she adds that “every member of society needs to defend their constitutional rights.”

Despite their employers’ reluctance to stand up for their rights in China or Hong Kong, this resolve to stand together is nevertheless a sentiment shared by many reporters on the ground. “Without wanting to get too Martin Niemöller about it,” a leading member of the FCCC told us, “you've got to stand up for stuff like this. Otherwise, there will be no one left to stand up for you.”