As China continued to post rapid economic growth numbers in the midst of the global financial crisis, pundits outside China sought to prize open its box of secrets. The result was renewed interest in what had already been dubbed the “China Model,” the idea that the country’s economic successes can be accounted for by a unique pattern of political and economic approaches that might enlighten us all.

Interestingly, but not altogether surprisingly, while the notion of a “China Model” has its origins in the West, it has been enthusiastically appropriated by thinkers on China’s conservative left, who have fashioned it into a defense of the Chinese Communist Party, its policies, ideology and system.

Last week, the CCP journal Seeking Truth ran a piece in which Zhang Weiwei (张维为), a research fellow at the Geneva School of Diplomacy and International Relations, summarizes what he sees as the eight principle characteristics of the “China Model” — including the prioritizing of facts over ideology, caring first about the lives of the people, and emphasizing stability. The article was apparently drawn from a speech Zhang gave to the Senate of the Netherlands, the upper house of the Dutch parliament.

But most interesting, perhaps, is Zhang’s emphasis in his preamble on China’s unique “national character.” His points here are important because they speak to the rootedness of the “China Model” — in the Chinese formulation — in the notion of what could be called Chinese exceptionalism. China, in other words, is completely unique among world nations, and as such no rules apply to China that are not China’s own. China will follow its own path — not that of the West — because only what is quintessentially Chinese can accommodate China’s unique “national circumstances,” or guoqing (国情).

Zhang describes China as the world’s only “civilization-type nation” — as though, he says, Rome never fell, but instead transformed into a modern nation-state. Unlike the other nations of the world, China has a vast territory, a vast and deep culture, broad regional differences and, most crucially, its own enlightened political traditions.

If the notion of American exceptionalism stems from the United States’ status as the world’s “first new nation,” it seems that Chinese exceptionalism stems from the fact that China is, as Zhang suggests, the world’s first ancient nation. That may sound silly, but Zhang has a flavor for the absurd — he claims at one point, after all, that Shanghai is already by some measures “perhaps better than New York.”

Zhang’s assertions are quite indicative of much Chinese writing on the China Model and its strengths. But in China’s controlled press environment, which hardly encourages fault-finding, rebuttals are a bit more difficult to find.

There is this wonderful volley by CMP fellow and now-missing Chinese “super blogger” Yang Hengjun (杨恒均) — we hope to have news of you soon, Old Yang — against the fuzzy facts of Naisbitt’s China Megatrends, now part of the laudatory canon of China Model slush.

One of the most thorough and intelligent pieces of writing to deal with the China Model, however, was written by CMP fellow Yang Jisheng (杨继绳) and published in the January edition of the liberal journal Yanhuang Chunqiu (炎黄春秋). In it, Yang briefly traces the history of the China Model and places Chinese proponents of the China Model squarely within a century-long tradition of opposition to Westernization — which, he argues, has long been a tool of the political (authoritarian) status quo.

Among the gems in Yang’s piece — including some staggering statistics on such things as annual national expenditures on official sedans (152 billion US dollars, or about 117 US dollars per capita) — is a 1940 quote from the philosopher Ai Siqi (艾思奇) that could have been written yesterday in response to Zhang Weiwei’s Seeking Truth piece: “All reactionary thought in contemporary China is of the same tradition — it emphasizes China’s ‘national characteristics’, harps on China’s ‘special nature,’ and wipes aside the general principles of humanity, arguing that China’s social development can only follow China’s own path.”

Nearly full translations of both the Zhang and the Yang pieces follow. That is a lot of material. But any reader interested in better understanding the debate going in China today — much of it behind the scenes — over the future direction of reforms, both political and economic, will be richly rewarded.

“The Analysis of a Miracle: The China Model and its Significance”

Zhang Weiwei (张维为)

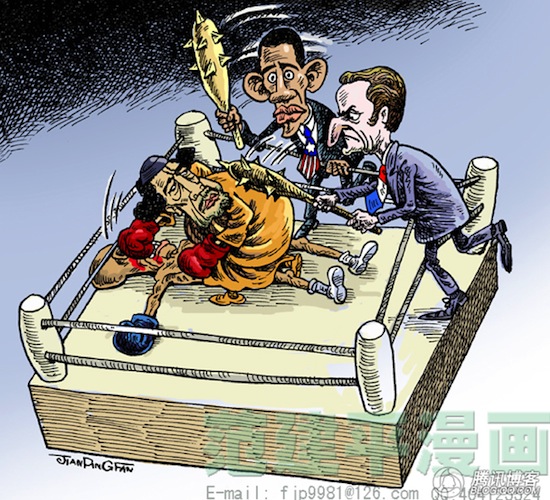

We know that for various reasons, China’s rise is a matter of great debate in the West. Over the past 20 years, the Western media have often portrayed China as a country where state power stands in opposition to the people, where political power is repressive, . . . Under the leadership of dissidents, the people carry out resistance. Some Europeans, some people in Oslo, for example, even believe that China is a magnified East Germany, or an amplified Eastern Europe, ripe for a so-called “color revolution.”

This point of view has driven many China experts in the West to make pessimistic predictions about China. They said first that post-1989 China would collapse. After the Soviet Union collapsed, they said once again that China would come next, torn by dissension and disintegrating. Around the time of Deng Xiaoping’s death [in 1997], they again predicted major unrest in China. Before Hong Kong was handed back [in 1997], they again predicted that the prosperity of the territory was gone for ever. When China joined the World Trade Organization, they again predicted that China would slide into collapse. When the financial crisis struck in 2008, they again guessed that there would be major unrest in China. In the end, all of these predictions were proven false. China did not collapse. Instead, the theory of the China collapse itself collapsed.

This successive failure of prediction suggests that we must research China, this complex nation, with greater objectivity. Perhaps, like the 17th-century Dutch philosopher Spinoza, or like his German contemporary, Liebniz, place the focus on what they called “natural religion.” What these men might care most about is how China has used methods material and worldly, and close to nature — rather than the theological methods of Europe in its glory — in order to govern society, the economy and politics. If we throw off the bonds of ideology, we discover that the things that have happened in China over the past 30 years are perhaps the greatest economic and social transformation that human history has even witnessed — around 400 million people throwing off poverty. This change has had a profound impact on both China and the world.

It can even be said that in the past 30 years, the achievements of China surpass those of all of the world’s developing nations put together, because 70 percent of those moving out of poverty [in the world] are Chinese. China achievements are greater than the achievements of all transitional economies put together, because China’s GDP has grown by a factor of 18 over the past 30 years, and by contrast the transitional economies of Eastern Europe have on average only doubled. Of course Eastern Europe has developed from a higher base. China achievements are also greater than that of many developed nations. That portion of Chinese who live at developed economy levels is around 300 million, equal to the population of America, and their level of prosperity is already no longer inferior to their peers in developed nations in southern Europe. First-tier Chinese cities like Shanghai have already in many respects surpassed New York. Whether in terms of such “hardware” as airports, subway systems, elevated rails, commercial facilities and civic architecture, or by such “soft” measures as life expectancy, infant mortality and urban safety, Shanghai is already perhaps better than New York.

Naturally, China has many problems of its own, and some of these are quite serious and require earnest action on our part. But China’s overall success is clear for all to see. How do we explain this success? Some people say it is a result of direct foreign investment, but in terms of per capita attraction of foreign investment, Eastern Europe has attracted more foreign investment than China. Some people say that [China’s success] owes to its pool of cheap labor, but labor is cheaper than China in a number of developing nations such as India. Some people say that [China’s success] owes to strong [centralized] government authority. But in Asia, Africa and Latin America there are many strong governments, but they have been unable to make the same achievements as China.

If these reasons are insufficient to explain China’s successes then we need to explore new trains of thought. My own explanation is the “China Model.” Before I explain the China Model, I would like to speak for a bit about my understanding of China’s national nature [or character]. This will help us to better understand the China Model.

China is not a magnified East Germany, nor is it an amplified Eastern Europe. Nor is it any ordinary country. China is a “civilization-type nation” (文明型国家), and moreover it is the only country of such a type in the world. Why? Because China is the oldest [nation] in the world with a history as a unified nation. China is the only country in the world to have 5,000 year of unbroken civilization. China is the only nation where a millennia-old civilization fully coincides with the morphology of a modern state. In order to illustrate this concept, I can give you a very accurate comparison. It is as though ancient Rome was never dissolved, and continued to the present day, making the transition to a modern nation-state, with a central government and a modern economy, incorporating traditional cultural elements, having a massive population in which everyone speaks Latin.

This sort of nation is necessarily different. The Chinese civilization-type nation has [what I call the] “four ultras”: ultra-populated, ultra-vast in terms of territory, ultra-ancient in terms of its historical traditions, and ultra-deep in terms of its cultural accumulation. Owing to this character of the “four ultras,” China’s rise must necessarily give rise to a widespread international impact. China’s population surpasses that of Europe, America, Russia and Japan combined. During the Spring Festival this year, 2.5 billion trips were made by Chinese. What kind of concept is that? Imagine that the entire populations of North America, Europe, Russia, Japan and Africa were on the move within the space of less than a month. This example can illustrate the enormous challenges and endless opportunities China now faces.

China is a vast territory, a continent with great regional differences. On any account you can imagine, whether state administration, economics, medicine, military affairs, ways of life, [these regions] all have their own traditions going back millennia. China also has an extremely rich culture, including excellent works of literature and architecture. The richness of China’s food culture can illustrate this. There are eight major food cultures in China, and each of these includes countless sub-types. Personally, I believe that any of these eight food cultures taken alone is in many ways greater in terms of variety than French cuisine, though I understand that in this forum some might take objection to this. All of this is essentially the product of China’s deep history. All of this determines the uniqueness of China’s development path. Now, turning back to the China Model. I personally believe that this model encompasses eight characteristics.

1. The first is “speaking the truth through facts” (实事求是). This is an ancient historical concept in China, one that Deng Xiaoping revived at the end of the “Cultural Revolution.” It was Deng Xiaoping’s view that the ultimate standard for determining truth was not ideological dogma, whether Eastern or Western — rather is should be facts. Through an investigation of the facts, China has come to the conclusion that neither the Soviet planned economy model nor the Western democratic model can make a developing nation achieve modernization. China therefore decided in 1978 to seek its own development path, and it took one kind of practical method to promote its own large-scale modernization.

2. The second is the prioritization of lives of the people. This too is a political concept derived from Chinese traditions. Deng Xiaoping defined the elimination of poverty as the first item of business, and he formulated and put into practice a series of practical measures to eliminate poverty. Reforms in China began in the countryside, because at that time the vast majority of Chinese lived in the countryside. The success of rural reforms drew along the overall development of the Chinese economy, resulting in the emergence of countless township and village enterprises and small and medium-sized businesses. They also created the foundation for the subsequent soaring development of China’s manufacturing sector. In many ways, the China Model’s characteristic of “prioritization of the lives of the people” also corrected a number of prejudices in the Western concept of human rights, for example that the political rights of citizens are always superior to other rights. This characteristic of the China Model will possibly have a profound impact on the fate of the poor who make up half of the world population.

3. Third is the preeminence of stability. As a civilization-type nation, the complexity of ethnicities, beliefs, languages and regionalism in China are second to no other place in the world. This character [of China] has given rise to the collective fear among Chinese of “chaos.” The traditional concept in China is of “times of peace and prosperity” (太平盛世), in which “peace” and “prosperity” always come hand in hand. This is why Deng Xiaoping repeatedly emphasized the importance of stability, because he understand better than anyone China’s own contemporary history — the fact that in the roughly 150 years from the Opium Wars in 1840 to Opening and Reform in 1978 China had at most 8-9 years of peace, and our process of modernization was constantly interrupted . Between foreign aggression, peasant uprisings, infighting among warlords, and ideological upheaval there were few years of peace. The past 30 years mark the first extended period of stability and development China has experienced in modern times, and only such an environment has made China’s economic miracle possible.

4. Fourth is gradual reform. China has a huge population, a massive territory and a complex situation, and this is why Deng Xiaoping employed a strategy of “feeling the rocks as one crosses the river” (摸着石头过河). He encouraged various kinds of experimentation with reform, and our Special Economic Zones were places where reform experiments were carried out, and taken nation after success was proven. China avoided “shock therapy.” We allow our imperfect systems to work while we carry out reform, serving the project of modernization. This characteristic has allowed China to avoid the paralysis and disintegration of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia.

5. Fifth is sequential differentiation (顺序差异). The overall sequencing of China’s reform has been as follows: first the countryside then the city, first the coastal areas then inland areas, first principally the economy then politics, first carrying out the simplest reforms then tacking the more difficult reforms. The advantage of this is that the first stages of reform pave the way with experience for the later stages, establishing foundations. Behind this method lies the holistic thinking (整体思维) of the Chinese tradition. As early as the 1980s, Deng Xiaoping formulated a 70-year strategy of transforming China into a developed nation. Today we are still carrying out this strategy. The capacity of this sort of wide-span holistic approach now stands in sharp contrast to the internal populism and political myopia so prevalent in many nations in the world (including many in Europe).

6. Sixth is the blended economy [approach] (混合经济). China has endeavored to organically combine the “visible hand” and the “invisible hand,” organically combining the strengths of the market and the economy, and effectively preventing the breakdown of the market. China’s economic system has been called a “socialist market economy.” As large-scale economic reforms have released massive market potential, the government has worked hard to ensure the stability of the macro environment. This is the principal reason why China was not implicated in the Asian financial crisis, and why it successfully negotiated the [recent] world financial crisis.

7. Seventh is opening to the outside world. The Chinese people do not have a missionary tradition, but they do have a strong tradition of study. Within the context of Chinese secular culture, studying the strong points of others is something honored with praise. China has maintained a tradition of selectively adopting the strong points of others. We have even learned much from the much-contested “Washington Consensus,” for example the entrepreneurial spirit (企业家精神) and the export-oriented economy. But China has through and through upheld its own policy space, deciding for itself what to adopt, and never following slavishly. Fully opening up to the outside has made China one of the most competitive countries in the world.

8. Eight is having a relatively neutral, enlightened and strong government. China’s government has been able to promote and achieve a widespread consensus on reform and modernization, and it can accomplish quite arduous strategic objectives, for example promoting the reform of China’s banking system, the reform of state-owned enterprises and the stimulation of the economy to deal with the global financial crisis. This characteristic has its origins in China’s deep and abiding Confucian understanding of a strong government (儒家强势政府观), in which the government must be good, virtuous and talented persons form the foundation. It was in China, after all, that the official examination system was established thousands of years ago. While our present political system has its inadequacies, it seldom produces leaders of low ability.

Fundamentally, the quality of a political system, including the source of its legitimacy, cannot be measured in its procedural correctness (程序的正确). More important is the correctness of its content, and this content, which is about achieving favorable political governance, must be measured by the people’s level of satisfaction. Good versus poor governance is far more important than democratic versus autocratic governance. If by “democracy”, that is, we refer only to the Western-defined “multi-party election system.” When we emphasize correct content over correct procedure, this is itself part of the Chinese political tradition, its goal being to create and perfect procedures as suits the needs of the situation of the nation and the people through the direction of good governance.

China today is in the midst of the world’s largest scale economic, social and political experiment. China’s successes on the economic front have already outlined the path of political reform in China — a gradual, experimental and accumulative approach to political reform in China. Throughout this process, we are willing to draw from methods old and the new, Chinese and foreign.

China is in the midst of its own industrial and social revolution, and naturally various problems have emerged. We face various challenges, such as rooting out corruption, bridging regional development gaps and closing the gap between rich and poor. In its development, however, China will keep to its own path, and will not behave according to other models. China has experienced more than a century of upheaval, chaos and revolution, and it has then experienced 30 years of successful economic reform and opening. The vast majority of Chinese wish to continue along the effective path of the China Model. This model has its own shortcomings, but it will continue to be perfected, because already it has done a good job of integrating with China’s own traditions going back thousands of years. China has its own historical inheritance. China has passed through 20 dynasties, of which seven lasted longer than American history.

As China rises, the influence of the China Model on the outside world will likely be greater and greater. China’s experience is fundamentally the product of China’s own national circumstances, and it is difficult for other countries to emulate. But a number of concepts and experiences involved in the China Model might have an international impact — things like speaking the truth through facts, prioritizing the lives of the people, gradual reform, constant experimentation, and the idea that “good versus poor governance is far more important than democratic versus autocratic governance.”

The world order today is undergoing a change of its own, from a kind of longitudinal world order to a latitudinal world order. The longitudinal world order is characterized by the West domineering other nations with its concepts and experiences, while the latitudinal world order is characterized by mutual cooperation among the concepts and experiences of various countries, with benign competition.

Finally, I’d like to share a story a European philosopher friend shared with me. One day in the second half of the 17th century, the German philosopher Liebniz came especially here [to the Netherlands], and he went to the Hague to meet secretly with the Dutch philosopher Spinoza. Why was the meeting secret? Because at the time Spinoza had been branded a heretic by the church. The two men discussed a number of odd things, including the secular, non-theological governance system of China. Actually, it’s my view that behind China’s re-emergence today lies still this non-ideological governance concept. After Liebniz visited Spinoza, he wrote a letter to a friend in which he said: “I’m planning to place a placard over my door that reads: ‘China knowledge center.'”

I tell this story not to encourage the Senate of the Netherlands to establish a China Office, but because the Netherlands has a world-famous tradition of China studies and research. But I still believe that we must continue to carry forward the spirit of the greats of the European age of enlightenment, particularly the spirit of openness and tolerance and the courageous pursuit of new knowledge. In a large sense, this is the spirit of the Dutch people. It is with this spirit that we must bravely go out and understand other cultures, other civilizations and other ways of managing state affairs — no matter how different these might seem.

If we move ahead in this way, we can avoid misunderstanding China through ideological prejudice. We can also in this way enrich our collective intelligence, better facing together the myriad challenges we face as humankind, such as the elimination of poverty, opposing terrorism, dealing with climate change, and preventing the clash of civilizations.

“How I See the ‘China Model’”

Yang Jisheng (杨继绳)

Yanhuang Chunqiu (炎黄春秋), January 2011

Posted online January 11, 2011

The “China Model.” This has become a hot topic today. But what is the “China Model”? What is the reason for talking about a “China Model”? What impact will it have on China’s reform process? This is my attempt to explore these questions.

What is the “China Model”?

The idea of the “China Model” came earliest from overseas, and from economists.

In the 30 years since economic reform and opening began, China’s GDP has maintained annual growth of around 9.8 percent a year. China, which before reform was an impoverished, low-income nation with average per capita national gross income of around 199 US dollars a year, has now entered the lower ranks of medium-level income with average per capita national gross income of around 2,000 US dollars a year. It has gone from being ranked 175th in the world [in terms of per capita income] to being ranked 129th in the world. China’s economy is expected to surpass that of Japan in 2010, becoming the world’s second-largest economy, second only to the United States — and its gap with the United States is steadily shrinking.

For some time, China was a nation in which goods were scarce. Now, China ranks first in the world in production of some 210 products, including steel, automobile, ships, cement, power generation, coal, chemical fertilizer, cotton, washing machines, refrigerators, air conditioners and color televisions (according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics). Before reforms, China was an insignificant member of the global economy. Now it ranks third in the world in terms of import-export, and ranks first in the world in foreign exchange reserves. China is also one of the most favored destinations for foreign direct investment. China’s economic miracle has caused foreign economists to sit up and take notice. And this is how the “China Model” originated.

American economist Andrew Michael Spence, a 2001 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economics, has said that we have never before seen an economy of the scale of China, which in such a short period of time could develop so fast, and that China’s economy is in a class by itself. Another Nobel Prize-winning American economist, Joseph Stiglitz, believes that against the background of a sluggish global economy, the “China Model” is inspirational. In the midst of the recent global financial crisis, China’s economy continued to develop rapidly. For this reason, the idea of the “China Model” spread more widely. And yet, in the eyes of economists, a “model” is a case in economic development. Take the recently fashionable “India Model,” for example, because for more than ten years the Indian economy has developed rapidly and could within the next few years surpass China. The “India Model” is different from the “China Model” in that China is principally driven by manufacturing, becoming the “factory to the world,” while in India’s case the service sector account for more than 50 percent of GDP, making it the “office to the world.” China’s economy is heavily reliant on the outside world, while in India domestic demand in the chief driving factor. China’s economy is driven by the government, while India’s economy is driven by the market (“Economic Development in India and the India Model”, in World Issues Research 世界问题研究, published by the Xinhua News Agency World Issues Research Center, Issue 286). We are rather familiar with the praise foreign economists have heaped on China’s economy. But actually, there has been a lot of praise for India’s economy as well.

But in the hands of political commentators, the whole content of the “China Model” has now been transformed.

In his new book How China’s Leaders Think: The Inside Story of China’s Reform and What This Means for the Future, Robert Lawrence Kuhn, the author of The Man Who Changed China: The Life and Legacy of Jiang Zemin explains the China Model. In his view, “For now and for the foreseeable future, the one-party rule of the Chinese Communist Party is the best option. An impractical democratic system would transfer resources to an endless political debate, and long and medium-term economic and social benefit would be sacrificed. It’s unlikely that an impractical democratic system would build a strong economy, and at the same time it could not possibly give the greatest benefit to the majority of people.”

John Naisbitt, who rose to prominence in the 1980s with his book Megatrends, argues in his new book China Megatrends that the China Model is a kind of “vertical democracy” (纵向民主). The top-down leadership of the government and the the bottom-to-top participation of the people [in China] has emerged as a new kind of political model, one that is different from the “horizontal democracy” of the West. “The principal advantage of vertical democracy lies in its ability to liberate politicians from the election-driven thinking, enabling them to set down long-term strategic planning,” Naisbitt writes. In Naisbitt’s view, this model has been one important guarantee of China’s successes over the past 30 years: “Looking back now, it seems there is no better method of leading such a massive and complex nation out of poverty and achieving modernization.”

British scholar Martin Jacques, the author of When China Rules the World: The End of the Western World and the Birth of a New Global Order, has written: “One important characteristic of the China Model is the concept of the big government and the avoidance of Western-style democratic concepts.”

Bruce Dickson, a China specialist at George Washington University, argued in one essay that “in order to enhance the implementation of these policies and check demands for equality and social welfare, authoritarian rule is necessary.”

These foreigners cannot possibly understand China within such a short period of time. Read their writings and you’ll find that they have entirely avoided very real contradictions in China, choosing only to see China’s brighter and fresher surface. They are far removed from the reality in China. Robert Lawrence Kuhn is a guest of China, and the government has offered him optimal conditions for his fact-gathering and writing. He thanks more than 300 people in this book, and among them are more than 100 provincial-level officials. The people he has interviewed are essentially system insiders listed out by the government. He interviewed no-one at the grassroots level, and the whole writing and fact-gathering process took just one year. We can’t expect to truly understand China through this hastily written book. At Jiang Zemin’s suggestion, Naisbitt opted for the theme of “China megatrends.” For this purpose, he organized a project team comprising three teachers from Tianjin University of Finance and Economics and Nankai University, as well as 20 students. The students were responsible for gathering the material. The project team extracted and compiled material from Chinese newspapers and then translated this into English to provide to Naisbitt. The project team selected newspapers from more than 100 cities, and the majority of these were local Party newspapers. Naisbitt didn’t require central-level newspapers, feeling that local newspapers would better reflect the situation among the people. He opted against selecting biased papers like Southern Weekend. What he didn’t realize was that local papers are also official papers. And of course we can’t expect that this China Megatrends spliced and abstracted from official newspapers would possibly reflect China’s future trends.

Here we must introduce the views of Japanese-American political scientist Francis Fukuyama. In 1989, Fukuyama published his book The End of History, in which he argued that “the history of the development of mankind is a common history trending toward free and democratic systems.”

Nevertheless, at the end of August 2009, Xinhua News Agency released an article adapted from translation called, “Japan Must Face China’s Century Head On (日本要直面中国世纪). In this essay, Fukuyama affirmed the superiority of the “China Model.” Fukuyama summed up the key points of the “China Model,” saying that the value core of China’s development model comes from thousands of years of political tradition, and can be defined as “a system of responsible authoritarianism.” The tradition, which is beyond the reach of the West, is of 1) a massive, highly centralized country; 2) with a highly-developed administrative system; 3) with a politics that emphasizes responsibility, realizing a doctrine of “people as the base.” Subsequent to the emergence of this article, a number of researchers checked [the language in the piece against] Fukuyama’s original words and found that this piece making the rounds on the Internet used Fukuyama “selectively” and out of context. For example, the following paragraph appears in the [Xinhua] article: “China’s political tradition and actual model have received attention from an ever increasing number of developing countries. Between the ‘democratic’ model of India and the ‘authoritarian’ model of China, more countries are enthusiastic about China, as the former stands for decentralization and gridlock while the latter stands for centralization and high efficiency.” But Wang Qian (王前) of the University of Tokyo translated Fukuyama’s original words as follows: “Looking at these countries and the democratic decision-making processes of democratic countries like India, many people praise the relatively rapid decision-making capacity shown by authoritarian countries like China. However, these kinds of authoritarian political structures have their own shortcomings. But there is no rule of law, and no monitoring through elections, the process of accountability is geared to the needs of superiors in the Communist Party and the Central Committee, and not to the needs of the public that the government should serve.”

Liu Qing (刘擎), a history professor at Huadong Normal University said (in the forward of Shu’s book), that Fukuyama valued China’s 30-year development experience and recognized the deep impact China’s unique tradition and political culture have had on the modernization process in Asia, believing that the unique character of the China model had important research value. But Fukuyuma, he said, had never given up one of his core concepts — that modern modes outside of liberal democracy would sooner or later face pressure to democratize, that they would encounter extreme difficulties and be difficult to sustain.

As foreigners hotly discuss the China Model, Chinese will not be left behind

In December 2009, The China Model: Reading 60 Years of the People’s Republic of China, a book edited by Peking University professor Pan Wei (潘维) was published. As soon as the book was published it was selected by the General Administration of Press and Publications for its “Classic China International Publishing Project” as an important work in transmitting China’s voice to the world. Pan Wei also traveled to various Confucius Institutes set up by China around the world, and to the British House of Commons, to talk about the “China Model.” In an article called “The China Model: Analyzing the Economy, Politics and Society Under the Chinese System,” Pan Wei sums up the basic arguments made in his book. His basic argument is that the “China Model” is formed by three sub-models — the unique economic model seen in the national economy; the unique political model of people-based politics; the unique social model of the state system (社稷体制). Pan Wei believes that people-based politics has four pillars. First, the democratic concept of modern doctrine of people-orientation (现代民本主义). Pan Wei believes that the idea of the people-oriented doctrine was already mature in ancient Chinese culture, and today is embodied in the concept of “serving the people” (为人民服务), of “exercising power in the interests of the people, sharing the feelings of the people, and working for the good of the people” (“权为民所用,情为民所系,利为民所谋). Secondly, [the people-based concept] emphasizes a system of selecting officials who have successfully undergone review. [According to Pan,] China’s official selection system, derived from its ancient imperial examination system, is a “top quality selection system” (绩优选拔制). In terms of its official selection criteria for officials, this system has much more flexibility, [says Pan], than competitive systems based on winning public opinion. Third, [the people-based concept emphasizes] an advanced, unselfish and united leadership group. Pan Wei believes that as a “political leadership core” (政治领导核心) the Chinese Communist Party is vested with these three major characteristics. Fourth, [the people-based concept emphasizes] an efficient system of government division of responsibilities, balance and correction of errors. Pan Wei believes that unlike the separation of three powers in the West, China’s [system] is one of separating responsibilities but not separating power.

“Separating responsibilities but not separating power” is about separating power within the context of concentrated power. How then is responsibility separated? Pan Wei sets out ten aspects of the responsibility separation process . . . [We have not translated Pan’s ten aspects, but refer interested readers to the Chinese].

In researching Chinese questions, Chinese scholars have an advantage over foreign scholars. If Mr. Pan Wei were to earnestly face social issues in contemporary China, leveraging a competent knowledge of both China and the West and his ambition of creating a “China studies school” (中国学派), he no doubt might make real achievements. Judging from his assertions, however, he not only — like Kuhn and Naisbitt — showers China’s current system in its entirety with unqualified praise, but he entirely affirms the 30 years of [China’s history] prior to economic opening and reform. He writes: ” . . . Success lies in our nation’s creation over 60 years of the path of the ‘China Model’, and the danger lies in deviating from this ‘magic weapon.'” Certain of his arguments are not without merit, but on many crucial questions he twists the facts of China’s history. He says that the “state monopoly on purchase and sale prices [of goods] during the planned economy era did not deprive farmers, but instead was more beneficial to farmers than market pricing.” Do Chinese farmers agree with this conclusion? Making excuses for numerous instance of large-scale suppression over these 30 years, he says: “The Chinese Communist Party did emphasize ‘class struggle. But unlike Western society, the target of struggle was not any concrete ‘class’ within Chinese society, but rather was confined to certain types of ‘thought’ and a finite number of people who stood for this type of thought, its goal being to create unity of thought, stabilize political power, and build and firm up socialism.” Is this a statement the tens of millions of victims [of that era] can stomach? He emphasizes the “separation of responsibilities” [but not separation of powers]. “The West emphasizes rights, but China emphasizes responsibility,” he says. “The ‘primacy of responsibility’ (责任本位) forms the foundation of the ‘China Model.'” But I would ask: “How can subjects without rights take on any responsibility? He criticizes those who say political reform in China has fallen behind by accusing them of using Western dogma to build a case about China. But I would ask: Deng Xiaoping said in the 1980s that political reforms had fallen behind, so was that Western dogma too? (NOTE: the views of Pan Wei I present here are those found in the electronic version of the book, The China Model: An Analysis of the Economy, Politics and Society in the Chinese System).

Pan Wei rejects the “dual division between democracy and autocracy,” and adopts out of context a number of concepts from Chinese imperial autarky, using them as weapons to resist democratic tendencies today. As an academic, Pan Wei should understand that academic scholars both inside and outside China have written whole libraries of books on the contrast between democracy and autocracy. How is it that without expounding on the issue Pan Wei can so lightly dismiss the idea? Denying the “dual division between democracy and autocracy” means denying every revolution against autocracy that has ever happened outside China. Pan Wei also denies the “dual division between planned and market economies.” Hasn’t China’s 30 years of reform been about transforming a planned economic system into a market economic system? It seems, according to what Pan Wei says, that this reform was entirely unnecessary.

Summing up the above, the “China Model” that a number of scholars outside China have advocated in recent years includes the following key points: 1. affirmation and praise for China’s current political structure; 2. affirmation and praise for the 30 years prior to economic reforms; 3. promotion of “centralization” and “big government,” and affirmation of “authoritarianism”; 4. rejection of modern democratic systems, and the denial of universal values; 5. a rejection of criticisms of Chinese imperial autarky from the May Fourth Movement onward, and calling for the worship of Confucius and the study of the Confucian canon.

If we affirm and praise the current political system then there is no need to carry out political reforms; if we praise and affirm the three decades before economic opening and reform, then the 30 years of reform were an unnecessary move. If we want to carry on and develop the fine traditions of Chinese culture (继承和发扬中华文化的优良传统), then [we can suppose that] the denial of Chinese tradition since the May Fourth Movement has in some sense gone too far. But the May Fourth Movement’s criticism of imperial autarky was a real and necessary awakening. Denying the process of awakening since the May Fourth Movement is to step back historically. The proponents of the “China Model” attribute the economic successes of the past 30 years to an authoritarian government, and this is not borne out by the facts in China.

During the planned economic era, China’s government was even more powerful. Why then was there no economic miracle? And the economic miracle of the past 30 years has come as the planned economy has been given up, causing the social forces pent up for many years to advance like never before. Proponents of the “China Model” promote centralized politics. The success or failure of centralized politics depends entirely on the vision and character of top leaders. In Plato’s ideal republic, the king was an all-knowing philosopher, but the weaknesses of human nature guarantee that not every ruler can be a “philosopher king.” Therefore, in this kind of political system, the nation is vested with uncertainty. Plato’s pupil, Aristotle, denied the position of his teacher. In his later years, Plato too parted ways with his “Republic.” After Aristotle’s day, centralized political systems emerged many times and in many different nations. But as time went on, these political systems gradually declined and more and more countries opted for democratic systems and fewer opted for autocratic systems. Modern democratic systems are a product of human civilization, and although they have not shortage of faults themselves, there is as of yet no system to better them. For the “China Model” to denounce modern democratic systems and offer as their replacement centralized political systems is clearly a foolish ploy.

The praise for the “China Model” today recalls for me the praise some academics in the West in the 1930s showered on the Soviet Union. The background at the time was that the West faced economic crisis while the Soviet Union outshone everyone. Today the countries of the West once again face economic crisis, and China shines above them. History has already shown that those academics who praised the Soviet Union were historically short-sighted, and I wish scholars today would not follow in their footsteps.

The Market Economy Driven by Power is Unsustainable

In 30 years of reforms, its not only the economy that has developed rapidly, but politics has made clear progress. Political progress can be seen in the following aspects: 1. the transition from class struggle as the core to economic building as the core; 2. the annulment of landlords, the rich, reactionaries, rightists and other political designations, making various types of people equal in political terms; 3. the abolition of a lifelong tenure system for leading comrades (leaders); 4. the transition from a paternalistic totalitarianism to an authoritarian politics of shared leadership, a transition from a system in which what one person says goes to a system of collective responsibility; 5. the division of power between the center and the regional, with regional areas now having relative independence of interests, powers and finances; 6. the fading of utopian visions and a focus on practical results; 7. the relative relaxation of ideological controls, and changes to the unified public opinion of the past; 8. [China’s] assessment of the world situation has changed, with the idea of “an age of peaceful development” replacing the notion of “an age of revolution and war,” with a stop to “anti-imperialism/anti-feudalism” and the support for world revolutions, entering the World Trade Organization. These above changes have brought a substantial increase in the freedom of Chinese people. Previous tensions in international relations have also been somewhat improved.

However, China presently stands a great distance from democratic politics. The level of public participation in national affairs is low; channels for expression are far from open; forces checking political power are weak; government power is overstretched; the party and government are not separate, and the party is still substituted for the government; the court system cannot gain independence [from the party]; there is no freedom of speech. China is still an authoritarian political system.

The idea of the “China Model” is a complete affirmation of the status quo in China. And China’s status quo is that of “authoritarian politics wedded with an imperfect market economy.” This kind of model has already decayed into a “market economy driven by power.”

In the “market economy driven by power,” national administrative organs control the operation of the market and involve themselves in market transactions. [In this system,] power becomes a commodity, and is even translated into capital; capital can also buy public power in its own interests. Power and capital are monopolized and social resources are forcibly controlled. People who are on the periphery, far from the center of power, find it difficult to employ their intelligence and hard work to prosper and raise their social status. The combination of overextended power and commercial greed has become a source of malfeasance/sin. The corruption of public power in China today has already surpassed any degree that can be borne by society, becoming a social cancer that the people universally feel to be painful.

Some people have used the term “crony capitalism” to describe the above-mentioned situation. I think this an inexact way to put it. First of all, this term “capitalism” was undefined early on in academia, and only in the early 20th century was it set up in opposition to “socialism.” As for what is “socialism,” this is to this day ill-defined. Second, and more importantly, “crony capitalism” avoids the responsibility borne by state power. But the principal cause resulting in social problems is the participation of state power in the market, and the control of the market by state power. Therefore, I believe the term “power market economy” more closely describes [the situation in China].

By necessity, the power market economy creates rent-seeking behavior. “Rent seeking” means the pursuit of “rent.” And what does “rent” refer to? Contemporary economic theory refers to “rent” as differential pricing income resulting from a lack of elasticity in supply. The lack of elasticity in supply owes to government controls and restrictions on competition in economic activities, which results in wider discrepancies between supply and demand. In ordinary language, [this means that] because the government places controls on economic activity, increasing the power of officials to interfere, those who are closest to state power enjoy special rights to hold “rent.” [NOTE: Generally, “rent-seeking” is understood as the attempt to derive economic rent by manipulating the social and/or political context in which economic activities occur.] In order to rent seek, those carrying out business activities bribe government officials. Those officials who benefit from rent in turn strive to preserve the system that enables rent-seeking and to create new institutions that enable rent-seeking. This process of rent-seeking and rent-creation results in a vicious circle in which corruption spreads and causes and effects are linked [on an institutional level].

Monopoly is the necessary consequence of the power market economy. Monopoly results not only in the distortion of the market, but also creates privilege. Presently, monopolies are concentrated in the large state-owned enterprise sector. Large-scale state-owned enterprises administered by the central government take the place of the original state industrial complex and carry out monopoly activities. They obtain monopoly rights to quality resources, for example petroleum, telecoms, tobacco, coal, aviation, railways, electric power, financial, insurance, et cetera. They make use of cheap resources, capital and favorable government policies to obtain monopoly profits, and they get to determine profit-sharing arrangements and workers’ wages. They can enter any high-profit sector. By contrast, the policy toward private enterprises is one of exclusion, control and annexation. Enterprises that enjoy administrative monopolies act in their own interests. Through various means they force the state to introduce policies that work in their benefit. High-level enterprise officials and high-level government officials can be interchanged. A government minister today can serve as the CEO of this or that enterprise tomorrow. And a sizable number of these interchangeable senior officials are the sons and daughters of high-level cadres, or others with close connections to them. Therefore, state-owned enterprises today are in a sense the clubs of the power nobility, the interest-sharing groups of the power nobility.

Under the conditions of the power market economy, fair dealing is impossible. Under this system, power is on top, power is worshipped. Everyone lives in a different power class. The power center is like a black hole that sucks in the wealth of society. People at different levels of power differentiation [within society] cannot possibly deal on equal terms. In dealings between someone with power and someone without, and in dealings between a power superior with a power inferior, it is always the former that wins out and the latter that is defeated. Or it is the former that wantonly carves up the latter.

The net result of rent-seeking, monopoly and unequal dealing must necessarily be an expansion of the gap between the haves and the have-nots. On the one side are those in control of millions, billions or tens of billions, and on the other are the masses of poor. In 2009, the Chinese government combined its standards for absolute and relative poverty, with the poverty line defined at an annual income of 1,067 yuan, or about 150 US dollars, raised to 1,196 yuan per capita per year, or about 170 US dollars, and average of .46 US dollars per day. According to this standard, by the end of 2009, 35.97 million people were brought out of poverty (State Council Information Office: “China’s Progress on Human Rights in 2009”, September 26, 2010). And according to the United Nations standard of 1.25 US dollars per day (or 38 US dollars per month) what is the population of Chinese living in poverty? Premier Wen Jiabao (温家宝) has said that China has 150 million people living under the poverty level established by the United Nations (Wen Jiabao, “Recognizing a Real China”, September 23, 2010, speech delivered at the United Nations in New York). The results estimated by experts suggested something higher than those given by Premier Wen Jiabao. This is because this 1.25 US dollar [daily] figure established by the United Nations refers to daily food consumption, while the poverty line figures set by China refer to daily income.

The power market economy creates social inequality. The most basic manifestation of social inequality in the midst of reform is where the costs of reform and the benefits of reform have fallen. The biggest benefits of reform have accrued to those who hold power, their relatives and their friends. Those who have least benefitted are workers and farmers. And in terms of the costs and risks of reform, the latter have borne the brunt.

The power market economy results in class rigidity [or a lack of social mobility]. Social mobility is about the hopes [and possibilities] of the lower classes changing their station in life, and it is a means of moderating social tensions. When a society is rigid and the lower classes have no hope [of rising], social tensions become more severe. During the first 15 years of economic reform and opening, social mobility in Chinese society was quite rapid, and factors of achievement (principally personal drive) were of greater effect than pre-existing factors (such as family and social standing). After the mid-1990s, pre-existing factors became of greater and greater importance and the effect of achievement factors (后致性) was weakened. As a result, our society started becoming rigid. In the past going to school could change one’s status. Now college graduates without good family standing find it difficult to find work. The rigidity of [social] class is not merely a result of restraints exercised by the upper classes, but has also created a kind of benefit mechanism: state power participates in market transaction – if you want to advance as an official or become one, you must get close to power – you cozy up to the children of cadres, allowing the children of cadres to advance into official positions and make money – those who assist the children of cadres in advancing and making money themselves advance to higher positions and make more money. Those children of cadres who are closer to the center of power, even if they do nothing more than sit at home, will find that people bring “official hats” right over and place them directly in their hands. This sort of benefit mechanism has resulted in hereditary social status.

Under the economic conditions of the power market economy, the powerful classes direct the policies and measures of reform, ensuring reform develops in the direction most advantageous to their interests, with the result that there is greater social inequality. Those reforms that harm vested interests have great difficulty in taking the stage, while those that benefit special interest groups are quickly introduced. Two classic examples of this are housing reform (住房改革) and reforms to the official use of cars by state officials (公车改革). In 1998, the State Council issued “State Council Document 23,” which stipulated that welfare housing distribution (福利性分房), [or the provision of special housing to Chinese from all walks of life, from government officials to ordinary work unit employees], would be ended, and a completely commercialized housing system put in its place (住宅商品化). After this [policy took effect], complete commercialization of the housing system did happen for ordinary Chinese, and purchasing a home became a great burden placed upon them. Meanwhile, vast amounts of property built by departments under the Central Committee of the CCP, the State Council and central ministries and commissions and classified as so-called “affordable housing” (经济适用房) — housing which low-income families alone were technically qualified to purchase — was sold off to civil servants [at these below-market prices]. This kind of covert [sale of] welfare housing was in some places more severe than in Beijing (Yang Jisheng: “Housing Reform, its Situation and Origins”, 住房改革的由来和现状, Yanhuang Chunqiu, May 2009). After 1990 there were an estimated 3.5 million cars in official government use (公务用车), and the resources consumed on these cars far surpassed state expenditures on scientific research, public health, education and other expenses. In 1998, the government formally rolled out reform of the official vehicle system. But in ten years there has not been the slightest bit of progress. By 2007, the number of official cars retained in China surpassed 5,221,755, and the annual cost of operating a single official car was 200,000 yuan (factoring in depreciation, repairs, fuel costs and the wages and benefits of the driver). The amount consumed nationally [on this practice] surpassed one trillion yuan, [or about 152 billion US dollars]. With China’s population of 1.3 billion, that amounts to an official government vehicle expense per capita of 798.7 yuan, [or 117 US dollars] (Bian Baowu: “Costly Official Sedans”, editor of China Economic System Reform Publishing House, 改革要情参阅, Vol. 6, Xinhua Publishing House, 2010, p. 22). Official use of cars cannot be reformed because “state power” has not been reformed.

The situation created by the system of the power market economy is like this: a superstructure of unchecked power, and an economic base of unmanaged capital (资本没有被驾驭的经济基础). China today faces two major tensions [or confrontations], that between labor and capital, and that between the government and the people. Tensions between the government and the people are principally about unchecked power. Tensions between capital and labor are principally about unmanaged capital. The idiomatic phrases “hatred of officials” (仇官) and “hatred of the rich” (仇官) and their social psychology arise from these tensions. [China’s] ever more numerous and ever more frequent mass incidents are an expression of the fact that these tensions are growing more and more severe.

Mass incidents [in China] have increased every year since the mid-1990s. In 1993, there were 8,700, in 1999 there were 32,000, in 2000 there were 50,000, in 2003 there were 58,000, in 2004 there was a dramatic leap to 74,000, in 2005 there were 86,000, in 2006 there were 90,000, in 2008 there were 100,000. No [official] figures have been released for the last two years, but the Weng’an incident in Guizhou (贵州瓮安事件), the Longnan incident in Shaanxi (陕西陇南事件), the Shishou incident in Hubei (湖北石首事件), and the Ma’anshan incident in Anhui (安徽马鞍山事件) as well as other large-scale and large-impact events have all occurred during these two years. Mass incidents involving rights defense actions by workers or farmers account for about 75 percent of the total number of incidents. As instability has emerged in society, the government has put its energies into “stability preservation” (维稳), [essentially the mobilizing of vast police contingents to deal with petitioners and others with social grievances]. Spending on public safety in China went up 16 percent in 2009, with total expenditures reaching 514 billion yuan, surpassing the national defense budget, about 2.6 times total expenditures on health and medical care, and approaching total spending on social security and employment (Hai Tao: “Government Stability Preservation in a Vicious Circle of ‘the More the Preservation the Less the Stabiity'”, 政府维稳陷“越维越不稳”怪圈, China Youth Daily, April 19, 2010). The government has spent all of this money, not on resolving the social problems at the root of instability, but rather in preventing ordinary Chinese from reaching Beijing to plead their cases for restitution. Controlling petitioning activities is now one standard by which the central leadership assesses the performance of local leaders, and “preventing petitioning” (截访) has become an integral part of the work of local governments across the country. As local governments have found themselves insufficient to the task, private “security companies” have arisen [to meet demand]. Beijing’s Anyuanding Company (安元鼎保安公司), [a private company found last year to have been operating “black jails” for petitioners], is one example . . .

[Yang here goes into other issues, such as rampant pollution].

Contrary to the complete affirmation of the “China Model,” we have here exposed various crises facing [China] today. These crises illustrate that the so-called “China Model” (essentially authoritarian politics + an incomplete market economic, which we can also call a power market economy) is already in a tight spot. The logical way out is to build “constitutional democratic politics + a complete market economy.” Constitutional democracy is a goal toward which China has struggled for more than a century, and it is a complete institutional system. This system can place checks on power, and it can manage [or direct] capital. As capital is presently [in China] a slave to power, checking power is of course the most important task between directing capital and checking power. Checking power means monitoring and supervising state power, limiting the scope of state power, and preventing state power from entering into market dealings.

A New round of Anti-‘Westernization’

The “China Model is the latest round of criticism of and resistance to so-called “Westernization” [in China]. Pan Wei opposes the idea of “the cult of Western ‘liberal democracy’, [which would] tear down the Forbidden City to build a White House [in China].” But in fact, the roots of anti-Westernization run deep [in China]. In order the rescue the Late Qing from crisis, a number of visionaries suggested studying from the West and began a vigorous Self-Strengthening Movement (洋务运动). As they learned from the West, wishing to avoid in the process the disintegration of the authoritarian system of the Late Qing at the hands of Western culture, they introduced the guiding ideology of “Chinese studies as the body, and Western studies applied” (中学为体,西学为用). Adhering to the “body” (meaning the authoritarian political system) was a basic political principle at the time. After the May Fourth Movement, a number of people of insight even more fiercely criticized the political tradition of Chinese imperial autocracy, and they promoted the study of the advanced experiences of the West. At the same time, forces emerged in opposition to “Westernization” and in support of Chinese traditional culture. Ever afterward the debate between [those who wished to] study the West and [those who] opposed “Westernization” never abated. Opposition to “Westernization” took on different content in different periods, but always in common [with past forms of opposition to “Westernization”] was the drive to preserve the prevailing political system and ideological system.

“Chinese studies as the body, and Western studies applied” (中学为体,西学为用), only makes use of advanced experiences of the West on the technical level, and on the level of systems and culture adheres to Chinese traditions. This is a mark of progress over complete exclusion [from the outside world], or being the cock who acts with valiance on his own dunghill. The failure of the Self-strengthening Movement (洋务运动) in the 19th century demonstrated that this road could not be taken in China. When proponents of “Westernization” (including such terms as “Europeanization” and “renewal”) who stood against the idea of “Chinese body, Western application” criticized the Self-strengthening Movement they said it was only “changing things, not changing methods” (变事而已,非变法也), and they advocated the study of the West on social and systemic level. For a long time, the debate over Westernization and anti-Westernization has raged on. In the 1930s there was again a debate between a “Chinese quintessence” (中国本位论) versus “total Westernization.” The idea of “Chinese quintessence” was raised in 1935 in an essay encouraged by the Kuomintang government and by written by professor Tao Xisheng (陶希圣) and nine others. Its motivating idea was to preserve the political power and ideological system of Chiang Kai-shek. The idea of “Chinese body, Western application” failed to preserve the “body” of the Qing Dynasty. Likewise, the “Chinese quintessence” failed to preserve Chiang Kai-shek’s “quintessence” [or fundamental standing]. Why is it that in round after round of this unending struggle between Westernization and its opponents, it is the conservative side that always loses out? This is because the various theories in opposition to Westernization are always taken up by the ruling authorities as tools for the defense of their interests and leadership status, particularly as theoretical tools in opposing democracy and defending autocracy. In 1940, the famous philosopher Ai Siqi (艾思奇) pointed out just this issue. He said: “All reactionary thought in contemporary China is of the same tradition — it emphasizes China’s ‘national characteristics’, harps on China’s ‘special nature,’ and wipes aside the general principles of humanity, arguing that China’s social development can only follow China’s own path” (Ai Siqi: “On China’s Special Nature”, 论中国的特殊性, from February 1940 edition, from Yan’an, of Chinese Culture).

From the end of the Qing Dynasty to the May Fourth Movement, one aspect of the opposition to “Westernization” was the promotion of continued “Confucianization.” The debate at the time was between “Westernization” and “Confucianization.” Marxism had by this time already emerged as a split in Western culture, and had resulted in the creation of a Soviet political system with Marxism as its theoretical foundation. “Westernization,” therefore, already included “Soviet-style Westernization” (苏联式西化) and “European/American-style Westernization” (欧美式西化). In modern times we also already distinguish between many schools [of Confucianism] when we talk about “Confucianization,” including traditional Confucianism and modern Confucianism. By the middle of the 20th century, “Soviet-style Westernization” had already taken on leadership status in China. China’s traditional culture had already been overturned by a form of Western culture (Marxism-Leninism), and another form of Western culture (European-American) had been pushed into opposition to it. In the process of “Soviet-style Westernization” there was also something of the flavor of “wholesale Westernization.” China’s traditional culture was branded as feudal dregs. Criticism of Confucius and Mencius went unabated. The “theory of inheriting old ethical values” (道德继承论) was criticized, and promoted instead was “stressing the present and fading the old” (厚今薄古), stressing for example Marxism-Leninism and de-emphasizing Chinese traditional culture. We modeled [ourselves] on the Soviet economic system, political system, and education system. Soviet education materials poured into China’s schools. We even introduce a number of Soviet words into our language without translation, such as the “soviet” (苏维埃) and the “Bolshevik” (布尔什维克). As a total Soviet-style Westernization was gripping mainland China, Taiwan was heading in its own direction, energetically preserving traditional Chinese culture. To this day Taiwan has more “Chinese characteristics” than the mainland.

Deng Xiaoping once said to the Polish leader Wojciech Jaruzelski: “The political systems in our two countries are both patterned on the Soviet model. It seems too that the Soviet model is not so successful” (“Deng Xiaoping: Carrying Out Political Reform According to our National Situation” 根据本国情况进行政治体制改革, September 29, 1986, in Building a Revised Version of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics 建设中国有特色的社会主义增订本, People’s Publishing House, March 1987, Volume II, p. 144-145). In the mid-1980s a new round of opposition to “Westernization” emerged [in China]. At the time those on the side against “Westernization” were actually supporters of “Soviet-style Westernization” (苏联式西化). In this era between centuries, the question is not one of using Western civilization to deny traditional Chinese culture, but one of using modern democratic systems to replace “Soviet-style Westernization.” Today, after three decades of reform, China’s economy has incorporated market economics, but its political system adheres to the Soviet model, so that China has slipped into the predicament of “authoritarian politics wedded to an imperfect market economy” (威权政治加不完善的市场经济). Russia has already thrown off the Soviet model, but the proponents of the “China Model,” still cherishing the “ineffectual broom” that others have already discarded, once again stir up an anti-Westernization wave, doing their utmost to preserve the current political system. How absurd it truly is. Today’s China Model is a defense of “Soviet-style Westernization,” but at the same time it defends previous opponents of Westernization by holding to [the path of] Confucianization (孔化). Nevertheless, this wave of anti-Westernization that these proponents of the “China Model” have raised is simply another spray of surf in a century-long campaign of anti-Westernization. As severe social tensions bring fierce calls for political reform, when the Chinese people thirst for democracy, can this tiny wave keep back the raging tide of Chinese democratization?