By QIAN GANG

Keyword: political system reform (政治体制改革)

Ever since the 17th National Congress in 2007, the Chinese Communist Party has shilly-shallied on political reform. For advocates of political reform who see it as essential to China’s continued development the signals emerging from the leadership have brought constant disappointment.

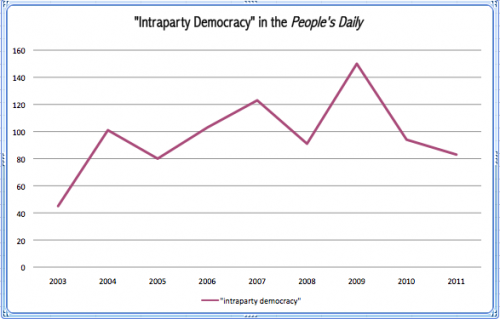

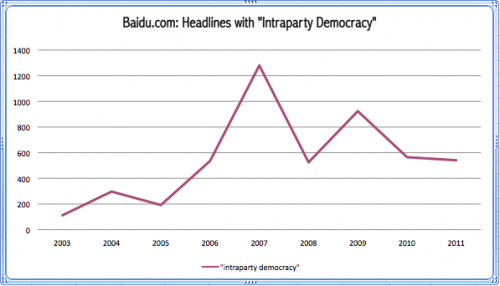

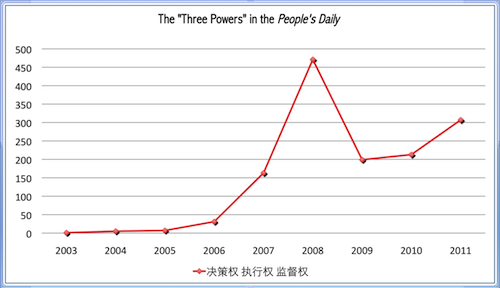

Searching the phrase “political system reform” — which can more simply be translated as “political reform” — in the official People’s Daily since the beginning of the 1980s, one derives a surge and sag pattern that mirrors quite closely the history of the Party’s engagement with this issue. Usage of the phrase surged before and after the 13th National Congress in 1987, during which time political reform was integral to the agenda. But the phrase fell precipitously in the wake of the June Fourth crackdown on protests in 1989, and has never recovered.

This is the historical pattern drawn by Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang, whose efforts to promote political reform in the 1980s ultimately failed, and by Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, who in the years that followed were unable to move out of the shadow of June Fourth and take steps in the direction of political reform.

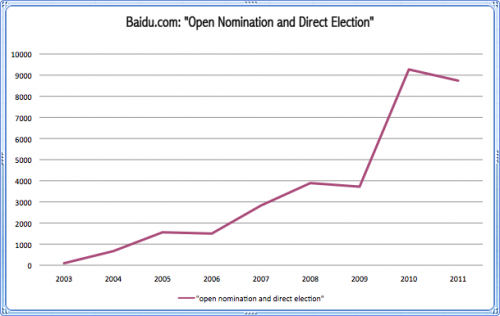

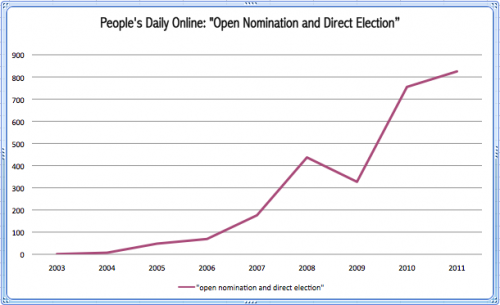

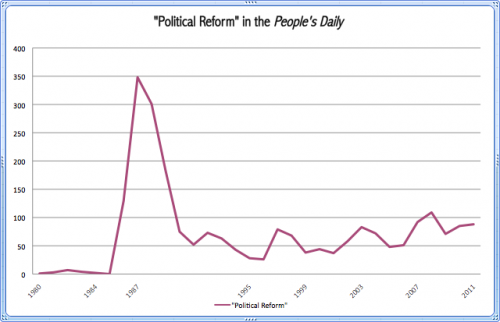

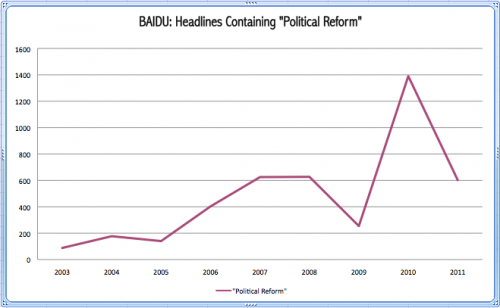

But China’s premier, Wen Jiabao, has called repeatedly in recent years for political reform, and popular voices clamoring for political reform have by some measures grown more insistent. The pattern emerging from a search, using China’s domestic Baidu search engine, of uses of “political reform” in news headlines since 2003 is quite different from the People’s Daily pattern above.

The graph shows that before and after the 17th National Congress in 2007, the term “political reform” rose generally in China’s media. These results are for all media, including Party-run newspapers, market-driven metro newspapers and magazines, and websites. The pattern may reflect broader expectations of political reform at the time. In 2009, however, China’s leaders introduced a concerted campaign to propagate the so-called “China Model,” and this clamor was accompanied by new attempts to stifle discussion of political reform. As China proclaimed that it had arrived at a glorious new model of development, it would certainly have been untimely to suggest there was an urgent need to reform.

In 2010, Premier Wen Jiabao made seven important references to political reform in within a period of weeks. He remarked in a CNN interview that “the people’s wishes for, and needs for, democracy and freedom are irresistible.” But another bump in the “political reform” curve followed, and once again, the discussion was quickly muffled.

During the first half of 2012, there were just 31 articles in the People’s Daily making use of the phrase “political reform,” a sign that Party media remained cold on the issue. But online articles using the term during the same period totaled 781, suggesting that the issue of political reform was enjoying a new high, surpassing even the bump in 2010.

Over the years of the Hu-Wen administration, Wen Jiabao has consistently been the leader within the Standing Committee of the Chinese Communist Party who has spoken out most insistently on the issue of political reform. Premier Wen has made eight government work reports to the National People’s Congress since taking office, and in every single one he has spoken of political reform. He has held eight press conferences for each of these NPC sessions, and at all but two of them (2005 and 2006) he has spoken directly about political reform. In 2007, in particular, he was insistent on the issue, exploiting each question raised by reporters as an opportunity to discuss his political reform views.

Fielding a question from a report in 2007, Wen Jiaobao said: “Things like democracy, rule of law, freedom, human rights, equality, universal love, these are not unique to capitalism. These are fruits of civilization that have emerged in common across the world through a long historical process, and they are values humanity pursues in common.” These remarks occasioned a series of fierce exchanges that year between liberal intellectuals and hardliners in China.

In October 2008, Wen Jiabao was interviewed by CNN’s Fareed Zakaria while on a visit to the United States. When Zakaria asked Wen what lessons he had taken from the Tiananmen Square crackdown on protests in 1989, the premier responded: “I believe that while moving ahead with economic reforms, we also need to advance political reforms; as our development is comprehensive in nature, our reform should also be comprehensive.” He added that in addition to greater rule of law, and more oversight exercised by the Chinese people, “We need to gradually improve the democratic election system so that state power will truly belong to the people and state power will be used to serve the people.”

[ABOVE: The China Media Project’s book on Premier Wen Jiabao and the political reform discourse in China in 2010.]

Wen again raised the political reform issue in 2010. In his government work report to the National People’s Congress in March that year, he said: “Without political reform, our economic reforms and modernization drive cannot possibly succeed; fairness and justice are brighter than the sun in the sky.” Five months later, he used the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone and other events of moment, such as his presence at the United Nations General Assembly, to further press the issue of political reform. His remarks seemed to become heftier with each utterance. He said on one occasion: “If we run counter to the will of the people, then the road ahead is a blind alley.”

In these instances, what have since become known in China as Wen Jiabao’s “seven mentions of political reform,” the thrust was that without political reform China’s economic reforms, and the gains they have brought, will ultimately fail. Further, he said, the problem of over-concentration of power and insufficient checks and balances had to be dealt with. The ruling party had to abide by the nation’s law and govern according to the Constitution. Finally, he emphasized that fairness and personal freedom were the ultimate measure of democracy and rule of law in a country.

Wen Jiabao’s political reform remarks were supported by many Chinese, but they were resisted by the Party’s upper ranks. The Central Propaganda Department responded by issuing stiff restrictions on coverage and discussion of political reform. On China’s Twitter-like Sina Weibo, then just over a year old but already a crucial platform through which millions of Chinese gathered with a thirst for information, both of the long and shortened forms of the term “political reform” were blocked.

Premier Wen was undeterred. On September 14, 2011, attending the World Economic Forum’s Summer Davos held in the Chinese city of Dalian, Wen delivered a speech in which he said, “We must continue to promote economic reform and political reform.” He added that China must “adhere to national governance by rule of law, reforming on an institutional level the over-concentration of power and [the problem of] insufficient checks and balances, protecting the democratic rights of the people and their legal rights and benefits, preserving fairness and justice in society.”

[ABOVE: Wen Jiabao addresses the Davos forum in 2009. Image from Flickr.com, shared by the World Economic Forum under Creative Commons license.]

Again, on June 15, 2012, Wen said as he addressed the Counselors’ Office of the State Council: “The goal we are pursuing is not just the development of the economy, but freedom and equality for the people, and comprehensive development.” He spoke again about democracy, both so-called intra-party democracy – essentially, more shared decision-making within the Party – and the “institutionalization and legalization of democracy in the political and social life of the country.”

Wen Jiabao’s most recent appearance was a speech delivered at Tsinghua University on September 14, 2012. Addressing the issue of universal values, Wen said that “democracy and rule of law, fairness and justice, freedom and equality, are ideals and goals for which all of humankind were striving.” He again called on China to be “unswerving in carrying out political reform, developing socialist democracy and rule of law, promoting social fairness and justice, and realizing freedom and equality for all.”

The scores of speeches in which Wen Jiabao has addressed political reform during his 10 years in office have come to form a kind of peculiar garden within the terrain of contemporary politics. Within the upper echelons of the Chinese Communist Party, he has gone the farthest in voicing his hopes and expectations for political reform. Based on his remarks, his political ideals can be distilled by two simple ideas: protecting civil rights and checking government power. While Wen’s ideas have met resistance at every turn, the Chinese media have done their utmost, against the odds, to utilize and pass along these “Wen-style utterances”:

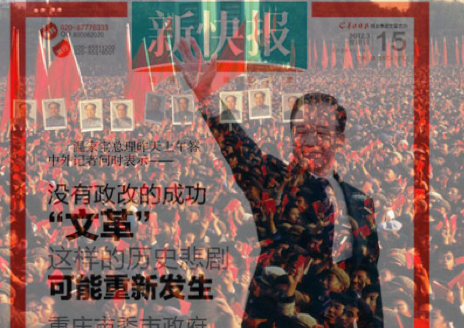

[ABOVE: A headline on the front page of the March 15, 2012, edition of Shanghai’s Oriental Morning Post reads: “Reform Requires the Awakening and Support of the People.”

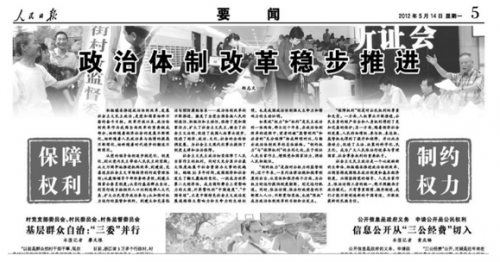

On May 14, 2012, the People’s Daily devoted an entire page to a special series of articles under the main headline, “Advancing Steadily on Political Reform.” The series purported to catalogue China’s progress on political reform since the 16th National Congress in 2002, the year Hu Jintao stepped into the presidency. There was nothing at all momentous about the content. Most interesting, however, was the page’s design, in which a pair of phrases were emphasized boldly with a traditional block-style print. “Protecting rights,” read the first. “Checking power,” read the second. Whatever the back-story on this People’s Daily page, this pairing of phrases was distinctly Wen.

[ABOVE: The May 14, 2012, edition of the People’s Daily. The birth of a new pair of watchwords?]

One important, recurring idea in Wen Jiabao’s remarks on political reform has been that the Party must act within the scope of China’s Constitution and its laws. This idea, acting within the law, first appeared in Zhao Ziyang’s political report to the 13th National Congress in 1987. It has since traveled an uneven road, disappearing in the report to the 14th National Congress in 1992, reappearing with newfound emphasis at the 15th National Congress in 1998, disappearing yet again five years later, and finally re-emerging in 2007 in Hu Jintao’s report to the 17th National Congress.

At the Summer Davos in 2011, Wen Jiabao said: “The most important task of a ruling party is to handle matters according to the constitution and laws, operating strictly within the scope of laws and the constitution. This means we must change the Party’s proxy control of government affairs, and the state of absolutization and over-concentration of power.”

One thing to watch at the 18th National Congress will be the leadership’s position on governance and law. Will the political report emphasize the idea that the Party must operate within the law, or will this phrase once again do a disappearing act?

Another political catchphrase that has become a familiar “Wen-style utterance” is “judicial independence,” or sifa duli. In fact, judicial independence is not a particularly sensitive phrase in China’s media. Every political report since 1987 has incorporated the concept of judicial independence, though the specific phrasing has differed in every case, and sifa duli has not expressly been used. On April 14, 2011, in a speech to newly-appointed members of the Counselors’ Office of the State Council, Wen Jiabao said: “We must uphold the rule of law, building a socialist nation of rule of law, in particular ensuring judicial independence and fairness.”

This is another watchword to watch closely at the 18th National Congress. Is it possible that “judicial independence,” or sifa duli, could sneak into the political report?

President Hu Jintao is far more ambiguous than Premier Wen Jiabao on the issue of political reform. While Hu Jintao has mentioned political reform, it is important to note that in the 13 plenary sessions of the Central Committee he has convened since coming into office, he has not once put political reform on the agenda for a “topic discussion”, or zhuanti taolun. In all his most important documents and speeches — from his “decision” on building a harmonious society in 2006, to his July 23, 2012, speech during a topic discussion with provincial-level leaders — Hu Jintao’s remarks on political reform have occasioned disappointment.

Hu Jintao has avoided singling out the issue of political reform. He has tended to lump political, economic, social and cultural reform together, so that no single priority is emphasized, and political reform fades into the larger pattern. Most importantly, Hu has said again and again that political reforms “must be unified with adherence to the leadership of the Party, the people as the masters of the country and governing the country by rule of law.” This phrase, a legacy of the Jiang Zemin era, is in fact meant to restrain political reform.

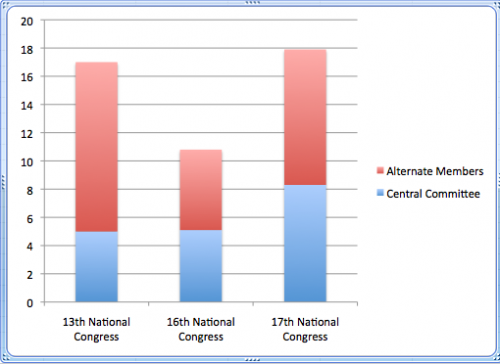

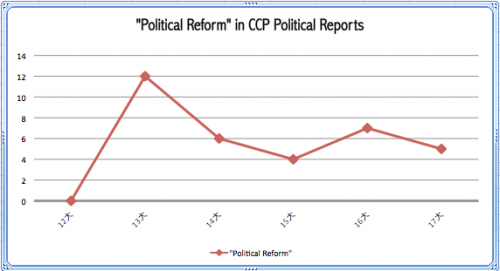

In my analysis of Hu Jintao’s political report at the 17th National Congress in 2007 I found that Hu had actually backpedaled on political reform. The principal sign of this was that the phrase “political reform” was not included in a section heading in the report, the first time this had happened since the 13th National Congress in 1987. Secondly, Hu Jintao made more frequent use of the “Four Basic Principles” in his own report than Jiang Zemin had in his report to the 16th National Congress in 2002.

The following graph can serve as a benchmark against which to measure “political reform” as it appears in the political report to the 18th National Congress.

Is there hope for political reform in China? This is of course a complex question. But the watchwords used in the political report to the 18th National Congress may give us some clue to related trends within the Party leadership. Will the phrase “political reform” appear more frequently, or more prominently, than it did in 2007? And will “Wen-style utterances” like “judicial independence” make their way into the Party agenda?