The term “Chaoyang Masses,” or chaoyang qunzhong (朝阳群众), is used by Chinese media, local police and internet users to refer to Beijing’s community network of public informants, essentially groups of neighborhood volunteers empowered to monitor their areas for illegal activities as well as breaches of moral and even political norms. While the Chaoyang Masses refers specifically to such volunteer groups within the Beijing district of Chaoyang, the term has gradually come to stand in more generally for such forms of mass mobilization for the public security (political security) objectives of the Chinese Communist Party. Similar district-based “community groups” (群众组织) in Beijing include the “Old Neighbours of Shijingshan” (石景山老街坊), the “Xicheng Aunties” (西城大妈) and the “Fengtai Advising Squad” (丰台劝导队). The growing prevalence of groups like the Chaoyang Masses across China points to deeper changes in the Xi era around the idea of “innovated” social governance, including the contemporary application of the so-called “Fengqiao experience” (枫桥经验), a Mao-era notion re-introduced by Xi Jinping.

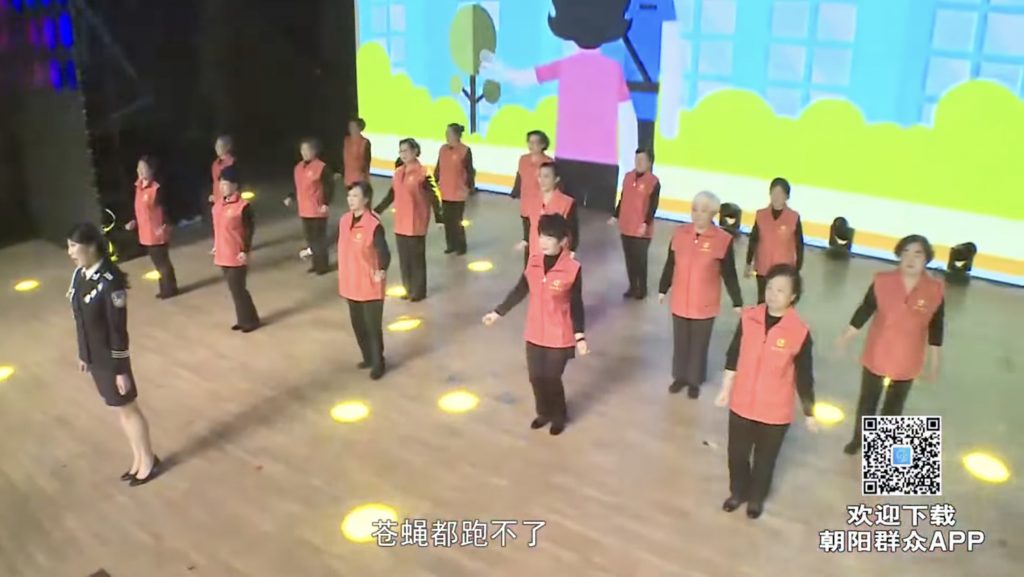

A new music video for the song “Chaoyang Masses” appeared online in October 2021. In this screenshot, the police woman sings that “Not a one [villain] will be let off the hook.” A QR code at bottom-right invites the public to download the “Chaoyang Masses” app and become involved in the movement to inform on others.

The arrests of a number of celebrities and influencers in Beijing in recent years have been announced by local police and official media while noting the involvement of the public, drawing attention to the use of volunteer groups to achieve community surveillance. The cases involving community informants have generally dealt with sex and drug-related crimes, including soliciting prostitution. But there have also been suspected, and sometimes patently obvious, links to political objectives.

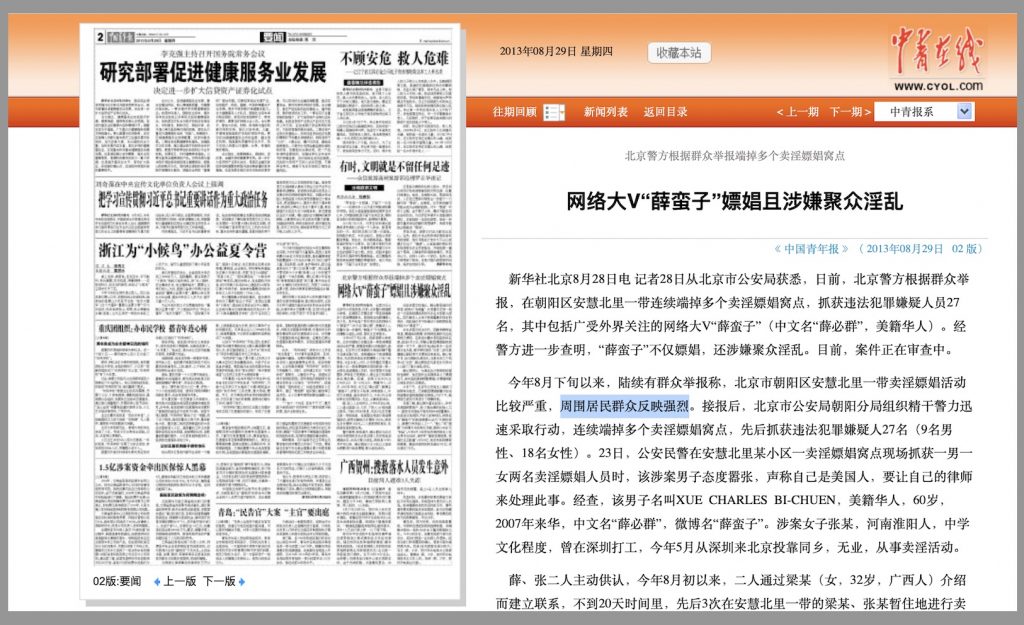

One such case occurred in August 2013 as police in Beijing announced the administrative detention of Chinese-American entrepreneur Charles Xue, or Xue Manzi (薛蛮子), an online influencer with millions of followers on Weibo who was known at the time for his outspoken critiques of politics and current affairs. At the time of Xue’s detention, a Weibo post from “Peaceful Beijing” (平安北京), an account operated by the capital’s Public Security Bureau (PSB), mentioned the arrest of a certain “Xue X” (the given name elided) who had been “reported by masses” (群众举报). It quickly emerged that the “Xue” in question was indeed Charles Xue, who had reportedly admitted his crime to Beijing police.

But Xue’s case immediately became enmeshed with the broader crackdown on so-called “Big Vs,” verified account holders on Weibo and other social media platforms who had a substantial base of followers and could often speak critically of the government (the English-language website of the Party-linked Global Times newspaper noted that Xue was known for his “aggressive online talks.”) In commenting on Xue’s detention, Global Times editor-in-chief Hu Xijin (胡锡进) brought suspicions of political motive clearly into focus:

It cannot be completely ruled out that the officials are ‘fixing’ Xue Manzi with this charge of soliciting prostitution. It is a common ‘unspoken rule’ for governments around the world to ‘fix’ political opponents through sex scandals, tax evasion, and so on. So we should kindly advise those who are keen on political confrontation that if they take this path, they should ensure that their own asses are clean.

The official Xinhua News Agency was even more explicit as it commented on the Xue case, dwelling not on the nature of the actual charges facing the entrepreneur, but rather on his online speech. In an article on August 29, Xinhua said that Xue’s detention was a “warning bell to all Big Vs about heeding the legal bottom line.”

However, cases like that against Charles Xue also brought into focus the increasing involvement of community policing groups in enforcing legal, moral and even (as the Xue case clearly suggested) political discipline.

In early 2015, the involvement of one community group in particular, the Chaoyang Masses (朝阳群众), received greater attention as they were continuously credited by police in Beijing. Cases involving the Chaoyang Masses were sufficiently common that mainstream media began seizing on the topic, explaining to readers who these volunteers were, and how active they had become. On March 12, 2015, The Paper (澎湃新闻), a commercialized online media outlet under the Shanghai United Media Group (SUMG) and the municipality’s CCP committee, published a story called, “Who Are the Mysterious Chaoyang Masses?” (神出鬼没的朝阳群众到底是谁?). The article noted that Beijing police had launched a special anti-drug operation between April and August of 2014 in which 926 drug-related crimes had been pursued. Of these, 740, or nearly 80 percent, had been “reported by the masses,” according to the article. Further, The Paper revealed that during the 2014 campaign, an estimated 850,000 “Beijing peace volunteers” (北京平安志愿者) had taken to the streets daily to assist police, and also that “100,000 people collected intelligence on terrorism.”

“Fallen stars, tremble!” The Paper wrote. But the article, shared across social media, was soon scrubbed from the internet, leaving only a message on the site: “This article has already gone offline.”

The Weibo post and article from The Paper also highlighted the intelligence gathering nature of the Chaoyang Masses, likening it to the CIA, MI6, the former Soviet KGB, and Israel’s Mossad spy agency – these being comparisons Chinese internet users made at the time, as the role of community policing groups became a topic of online chatter. Such comparisons would emerge also during subsequent waves of attention to the Chaoyang Masses and other groups.

On March 31, 2015, the Chaoyang Masses were again praised by police for having been essential in a seizure of drugs. In a post to official Weibo account of Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau, “Peaceful Beijing,” police said: “We can’t solve drug cases without the support of everyone, especially those who provide clues to the police. We thank the omnipresent ‘Chaoyang Masses,’ who are filled with a sense of justice, and who despise evil.”

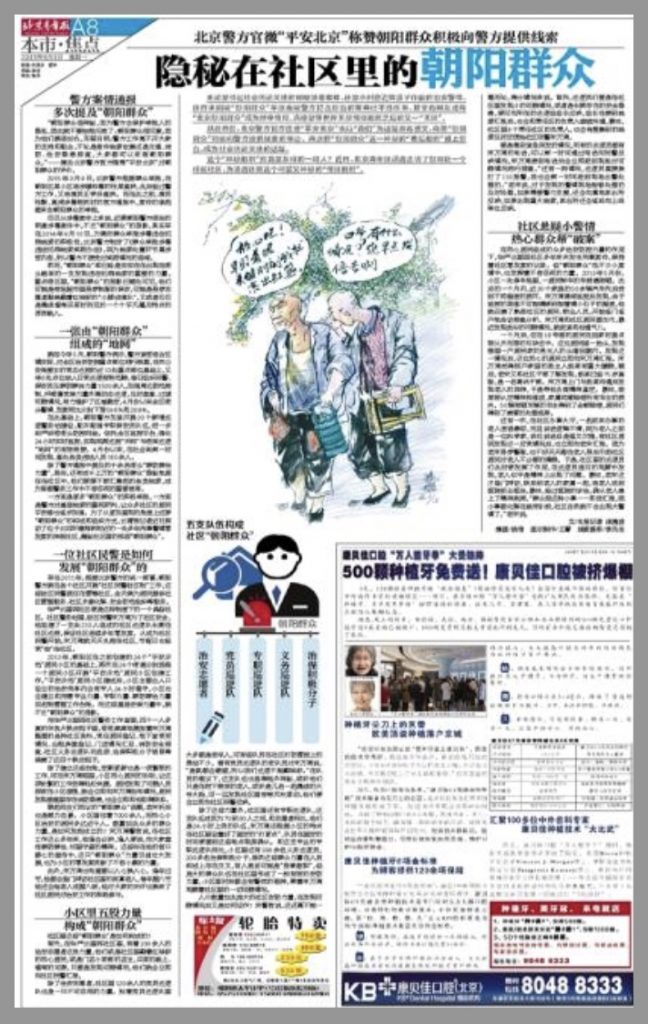

Finally, in June 2015, the Beijing Youth Daily newspaper, published by the Beijing chapter of the Chinese Communist Youth League, followed these cases by profiling the community policing group, referring to it as “adorable and mysterious,” and again noting that internet users had marveled at the efficiency of the Chaoyang Masses, saying the group rivaled foreign intelligence agencies.

According to the Beijing Youth Daily report, the Chaoyang Masses are comprised of five categories of people engaging in community policing. These include “security volunteers” (治安志愿者), “Party member patrol teams” (党员巡逻队), “full-time patrol teams” (专职巡逻队), “compulsory patrol teams” (义务巡逻队) and “public security activists” (治保积极分子). Each of these groups, said the report, has a distinct identity. They might include uniformed security guards posted in malls, volunteers wearing special outfits with red armbands, or even ordinary-looking seniors who pass residents on the street.

In 2016, the Chaoyang Masses were selected by China’s Ministry of Justice and the state-run broadcaster China Central Television as the year’s “Most Influential Actor for Rule of Law” (年度法治人物). Reporting on the group’s selection, The Paper repeated the volunteer figures for Beijing in 2015, mentioning 850,000 registered security volunteers, including 130,000 members of the Chaoyang Masses. This meant, in the case of Chaoyang District, an average of 277 volunteer informants for each square kilometer. For the whole of the capital, volunteers had provided police with “more than 210,000 pieces of intelligence” (情报21万多条).

In 2017, the activities of community policing groups in Beijing were digitized with the release by the Beijing PSB of an app called “Chaoyang Masses HD (朝阳群众HD).” The app allowed users to reach police immediately and confidentially, sharing reports of suspected violations along with related photos or videos. The police also provided cash rewards for those who provided actionable information.

When president Xi Jinping made an official inspection visit through Beijing in 2017, he specifically mentioned the Chaoyang Masses and other community policing groups. “Cities of people should be built and managed by the people, and it is not enough to rely on government power alone,” he said. “Beijing has its own good traditions, such as ‘Chaoyang Masses’ and the ‘Xicheng Aunties.’ Where there are more red armbands, there will be greater security and greater peace of mind.”

The endorsement of Chaoyang Masses is related to one of CCP’s core policy in terms of social governance, which is “stability maintenance,” or weiwen (维稳), a term that is short for “protection of stablity” (维护稳定). The term weiwen was originally an internal term used by the People’s Armed Police (PAP), the paramilitary force responsible for internal security. However, the term later became a core notion used more broadly within the CCP wo refer to issues of security in domestic and international issues, including anti-corruption, anti-terrorism and territorial concerns. With their omnipresent human surveillance capabilities, reaching into all corners of the community, groups like the Chaoyang Masses and the Xicheng Aunties are seen as “ace partners” for stability maintenance (维稳王牌).

The increasing prevalence of community policing in China also relates today to Xi Jinping’s reinvigoration of the Mao-era notion of the “Fengqiao experience” (枫桥经验), a mythologized approach to social and political governance that essentially directs the masses themselves to carry out on-site “rectification” of so-called “reactionary elements” in society. Before Xi Jinping rose to the position of general secretary in late 2012, no top Chinese leader in the reform era had ever been quoted publicly in the People’s Daily or other state media praising the “Fengqiao experience.” In 2013, however, as the CCP marked the 50th anniversary of Mao Zedong’s written instructions on the practice, Xi Jinping broke this pattern by issuing “important instructions on the development of the ‘Fengqiao experience.’”

In October 2021, a song called “The Chaoyang Masses” became a trending top on the Chinese internet, coming just days after the arrest of world-renowned pianist Li Yundi (李云迪) on charges of prostitution. Li Yundi’s arrest sparked renewed interest online in the Chaoyang Masses, referred to again as a “mysterious” neighborhood watch group. Once again, Chinese internet users expressed astonishment at the apparent effectiveness of these anti-crime volunteers. “I’m confident that the Chaoyang Masses could entrap even 007,” said one internet user. “The Chaoyang Masses are so capable that they could make the FBI sweat,” said another.

The first line of the trending song said, ominously:

Look at the headlines today,

Another villain has been booked.

Those who act badly, gamble or do drugs,

Not a one will be let off the hook.

看看今日的头条,

又有坏人被举报.

不正之风黄赌毒,

一个都逃不掉.

Stella Chen

CMP Senior Researcher

The CMP Dictionary

C

D

F

G

M

N

P

S

- Scaling the Wall

- Science

- Second-Generation Reds

- Security

- Seeking Progress in Stability

- Seeking Truth From Facts

- Self-Revolution

- Seven Bottom Lines

- Six Adheres

- Smart Governance

- Sneaky Visit

- So-Called

- Socialite

- Soft Resistance

- Soul and Root

- Soundless Saturation / Quietly Nourishing

- Sovereignty

- Speaking Politics

- Streamlining Services

- Strong Cyber Power