THE CMP DICTIONARY

Chinese Discourse and Narrative System

Chinese Discourse and Narrative System

In remarks at a Politburo study session in June 2021, President Xi Jinping called on Chinese Communist Party (CCP) cadres and state-controlled media to “accelerate the construction of a Chinese discourse and Chinese narrative system” (加快构建中国话语和中国叙事体系). This call received an even more high-profile hearing the following year during the 20th CCP national congress and again in June 2023, with Xi saying that this “system” is needed in order to “explain Chinese practice with Chinese theory.”

Xi Jinping was essentially making the point that China needed a value system, and a way of expressing that value system, that could establish the uniqueness of Chinese practice as the country moved to assert itself more actively in the world — distinctly Chinese packaging for distinctly non-Western concepts and practices.

It is somewhat ironic, then, that the concept leans so heavily on European literary theory. Presenting at a conference in December 2022, Professor Shang Biwu (尚必武), Associate Dean of the School of Foreign Languages at Shanghai Jiaotong University, traced the term back to the work of the French critic and philosopher Roland Barthes, who he quotes as having written that “narrative is present in every age, in every place, in every society… it is simply there, like life itself.”

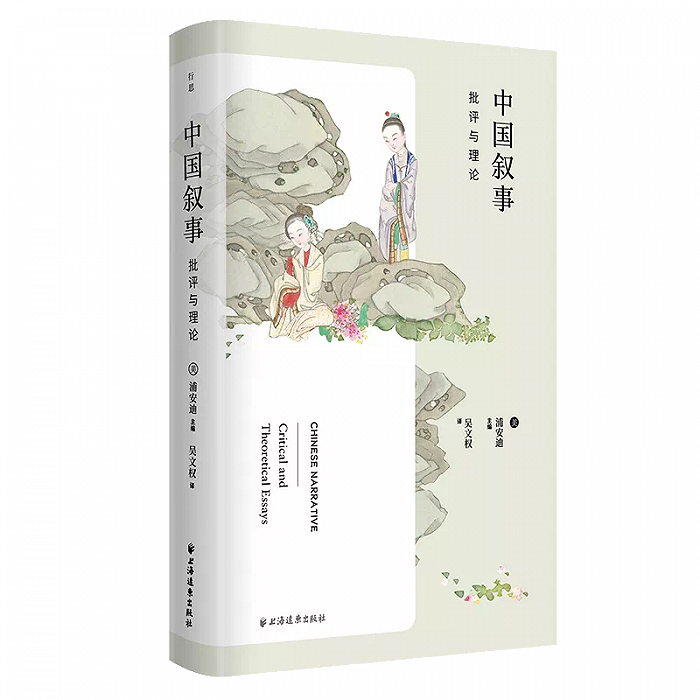

In expounding the idea’s importance, Shang also references the work of American sinologist Andrew H. Plaks, whose 1977 edited volume Chinese Narrative: Critical and Theoretical Essays attempts “a comprehensive critical theory for dealing with the Chinese narrative corpus.” Plaks and the other contributors argue that the genres developed by literary studies in the West cannot be tacked onto the Chinese literary tradition, where great works like the Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Water Margins blur the lines between history and fiction, the episodic and the thematic. The organization and presentation of Chinese writers’ worlds are inherently different, Plaks argues, because they are informed by a fundamentally different worldview — and this demands a different framework to be fully understood.

For comparative literature nerds, this is all exquisite food for thought. But in the context of contemporary Chinese political discourse, the term is invariably paired with the external propaganda goals of the PRC, like “strengthening soft power,” “civlizational influence,” and “telling good China stories.” So what does it have to do with Xi Jinping’s mission to expand Beijing’s influence abroad?

Framing Xi’s “New Era”

A piece in the August 14, 2023 edition of Seeking Truth, the CCP’s flagship theoretical journal, illustrates just how far “Chinese discourse and narrative system” in Party-speak has moved from its origins in critical theory. In it, vice-principal Liu Haichun (刘海春) of the Guangdong University of Foreign Studies writes that “to strengthen the Chinese nation, it is necessary to create a trustworthy, lovable, and respectable image of China,” echoing remarks by Xi to a collective study session of the Politburo in May 2021.

“By accelerating the construction of a Chinese discourse and narrative system, telling good China stories, and projecting China’s voice,” Liu adds, “China’s circle of friends in the international community will continue to grow, and China’s development will gain wider recognition worldwide.”

Occurrences like this alongside other propaganda policy aims make it clear that “Chinese discourse system and Chinese narrative system” — as it is understood and instrumentalized by the Party — bears little resemblance to the work of Barthes or Plaks. The stories it wants to be correctly understood are not classic, beloved yarns like The Plum in the Golden Vase or Dream of the Red Chamber; they are “stories” that will make people love and respect the People’s Republic under Xi Jinping — the stories they tell about themselves.

Professor Shang of Shanghai Jiaotong University drives this point home when he proposes an interpretation of what Xi means when he talks about a “Chinese discourse and narrative system.” When we speak of a Chinese narrative system, Shang writes, “Our focus may be on revealing the narratives of the nation, its culture, its history, and its encounters with distinctly Chinese elements and characteristics.”

Such “narratives” are intrinsically a reflection of the party-state. They lie at the confluence of several streams of thought in Xi’s vision for the country: Chinese exceptionalism and the resurgence of a uniquely grand human enterprise; the all-encompassing framework of “civilization” and the “civilizational state” as embodied by China; and the challenging of “Western” or “universal” norms at every available venue.

The “teleology of revolution,” an understanding of the past that defines the current regime’s violent seizure of power as a historical inevitability, is an idea already familiar to China and virtually every other communist nation. Their rule is portrayed as a predestined outcome, not an accident delivered by the ineptitude of their predecessors or the vicissitudes of global politics that, with a few variables reconfigured, could have gone another way.

A March 2023 article in Outlook New Era, a Hong Kong-based magazine dedicated to “promoting the development of socialism with Chinese characteristics for the new era,” makes the connection between Xi’s “Chinese discourse and Chinese narrative system” and his rule explicit: the “source material for Chinese stories,” writes the author, must comprise not only “the course of China’s revolution, construction and reform,” but also “the great practices underway in the new era” under Xi Jinping.

The precise aims of this “Chinese discourse and Chinese narrative system” remain nebulous. Still, by establishing a framework for how all stories from China’s past and present are understood, it offers something that merely “telling good China stories” cannot: the opportunity to establish a teleology not just of revolution but of Xi himself — one that is simply there, as Roland Barthes might say, like life itself.

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

The CMP Dictionary

C

D

F

G

M

N

P

S

- Scaling the Wall

- Science

- Second-Generation Reds

- Security

- Seeking Progress in Stability

- Seeking Truth From Facts

- Self-Revolution

- Seven Bottom Lines

- Six Adheres

- Smart Governance

- Sneaky Visit

- So-Called

- Socialite

- Soft Resistance

- Soul and Root

- Soundless Saturation / Quietly Nourishing

- Sovereignty

- Speaking Politics

- Streamlining Services

- Strong Cyber Power