Since the lead-up to the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in 2022, “era-ization,” or shidaihua (时代化), has become ubiquitous in the pages of the state-run press, conjoined in the official discourse with the term “sinicization” (中国化). Together, the two phrases define two important ideological goals of Xi Jinping’s unprecedented third term — defining Marxism in line with China’s realities (something China’s leaders for generations have emphasized), and also in line with the country’s unique character in Xi’s so-called “New Era.”

According to most English translations of CCP theory and jargon, shidaihua is “modernization.” However, rendering the term “era-ization” better captures the most essential import of the term, which is to identify Xi Jinping himself as an important and defining creator of Marxism for the modern era, thereby reinforcing his power and legitimacy.

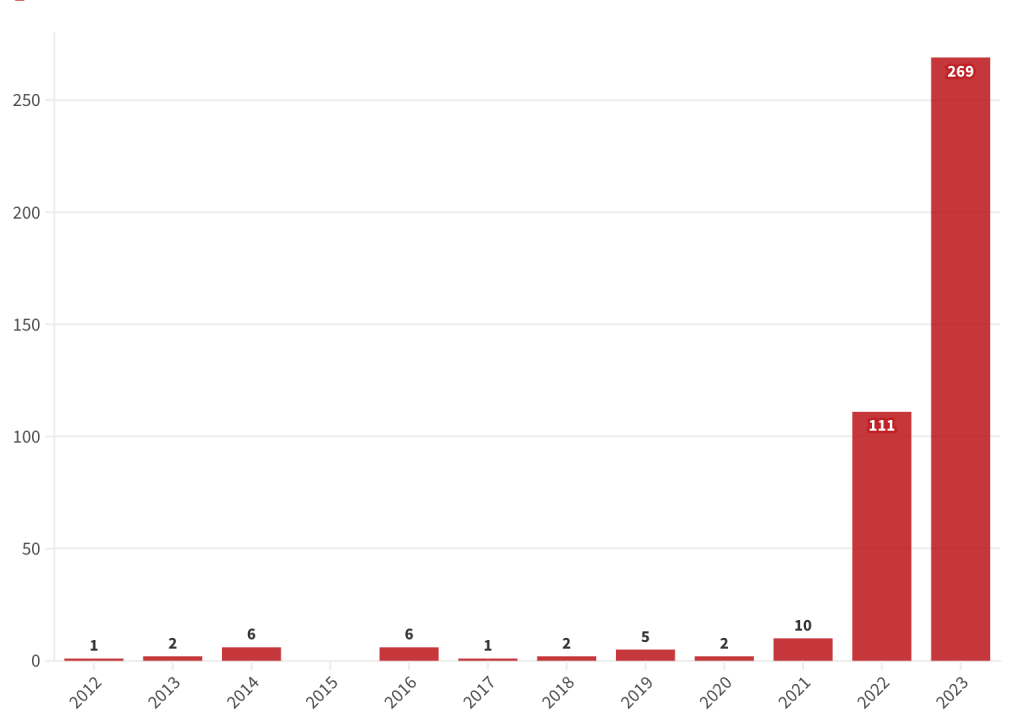

Baidu search results for pages featuring shidaihua in the headline show the term’s appearances in official media have exploded over the past two years.

Notably, the Chinese used to denote this is not xiandaihua (现代化), which is what you will find in any English-Chinese dictionary under “modernization.” Whereas xiandaihua literally means “to make (hua) like the modern era (xiandai),” shidaihua means “to make like the era (shidai).” It is not a new term in Chinese — it means “to change according to time” — but it does not easily translate. Thus it is repeatedly rendered as “modernization” without any care given to the fact that it is a different word with meaningful, if subtle, distinctions.

In two relevant articles from June 2023 in the Party’s official theoretical journal Qiushi, shidaidua appeared 14 and 27 times, respectively, while xiandaihua appeared 36 and 143 times. Conflating the two into the single English word “modernization” is untenable when the pair are so extensively used within a single piece of writing. With the two concepts now likely to appear multiple times within the same sentence, the need to draw a clear line between the two should be obvious.

Getting with the times

“Era-ization” may not roll off the tongue but it strikes at the heart of what the process is really about: the bending of old dogma to the will of the General Secretary and the reality he creates.

The aforementioned Qiushi pieces offer insights into the differences between “modernization” and shidaihua. Yan Xiaofeng, the dean of Tianjin University’s school of Marxism, writes in one that “the CCP’s promotion of the sinicization and shidaihua of Marxism is the process of advancing Marxism to guide China’s reality, incorporating the new features of the times” and “answering a series of major epochal questions.” Both “new features of the times” and “major epochal questions” employ the same modifier, shidai. Chinese readers will recognize the character from another propaganda phrase that has become omnipresent under Xi Jinping: the “New Era” (新时代).

“Era-ization” may not roll off the tongue but it strikes at the heart of what the process is about: the bending of old dogma to the will of the General Secretary and the reality he creates, whatever that may be and however it may change over the course of his reign.

Whereas modernization is the adaptation of Marxist theory to current conditions, “era-ization” is the adaptation of Marxist theory to the conditions attributed to Xi Jinping with implications of special glory — in a way somewhat redolent of the era names (年號) of bygone emperors.

Above and beyond modernity

When it comes to setting era-ization apart from modernization and “Chinese-style modernization” (中国式现代化), context is key.

China’s ‘Xivilizing’ Mission

In Qiushi, Tianjin Univesity’s Professor Yan points out that modernization has take as many forms are there are nations: “The diverse nature of modernization in various countries have been clearly identified,” he writes. “There is no single model of modernization in the world, nor is there a one-size-fits-all standard of modernization.” The sentiment is laudably broad-minded. Yet when it comes to the meaning of modernization within China, there can only be one way:

The essential requirements […] are adherence to the leadership of the Communist Party, adherence to socialism with Chinese characteristics, the realization of high-quality development, development of people’s democracy in the whole process […] and the creation of a new form of human civilization.

Beijing’s now-constantly repeated claim to have “shattered the myth that modernization equals Westernization” commits it to the belief that modernity as an idea exists beyond its political control. “Modernization,” therefore, can be dangerously open to popular interpretation. Era-ization, on the other hand, does not exist independent of political conditions — it is those very conditions and the need to adapt to them in thought as well as deed.

Era-ization is also closely linked to the Two Combines, which demands that Marxism adapt not only to China’s material conditions as Deng Xiaoping proposed but also “China’s excellent traditional culture.” Yan writes that “the Two Combines is the means of sinicizing and era-izing Marxism; Chinese-style modernization is the product of the Two Combines.”

Two Combines

In Doing Things with Words in Chinese Politics, Swedish sinologist Michael Schoenhals writes that “when the CCP leadership approves of a certain formulation, it does so because the formulation is judged to be politically useful and clever. A highly scientific formulation is one the state can use as a powerful tool of political manipulation.”

Untangling the knot

Untangling the rhetorical Gordian knots like the one above, therefore, may be less instructive than observing the utility of these words. Consider Wuhan University’s chief philosopher Li Dianlai, who in a July 10 “academic roundtable” published in the People’s Daily wrote that the “second combine,” which both enables sinicization and era-ization and is the “profound summary” of the two, represents “mental emancipation” and “profoundly reveals that the excellent traditional Chinese culture [i.e. not Marxism] is the root of our Party’s theories.”

Cleaving modernization from era-ization allows the two to go in completely different directions. In some cases, era-izing Marxism can mean undoing the modernization of Marxism under previous leaders, like by regressing to pre-Reform Era tropes such as the personality cult. As Li Dianlai implies, era-izing Marxism can also mean disregarding Marxism entirely and reaching further back into China’s “excellent cultural traditions.”

Like all the best tifa, era-ization is as formless and shapeless as water, ready to fill any vessel it is poured into. One moment it can flow gracefully around rhetorical monuments to diversity and tolerance; the next, it can come crashing down like a waterfall on anyone who envisions a different path for China than the one laid out by the Party and its leader.

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

The CMP Dictionary

C

D

F

G

M

N

P

S

- Scaling the Wall

- Science

- Second-Generation Reds

- Security

- Seeking Progress in Stability

- Seeking Truth From Facts

- Self-Revolution

- Seven Bottom Lines

- Six Adheres

- Smart Governance

- Sneaky Visit

- So-Called

- Socialite

- Soft Resistance

- Soul and Root

- Soundless Saturation / Quietly Nourishing

- Sovereignty

- Speaking Politics

- Streamlining Services

- Strong Cyber Power