The idea of external propaganda, if not yet the concrete term, emerged as early as the 1920s in China, as the newly founded Chinese Communist Party sought to engage with overseas counterparts through the Comintern Congress (共产国际代表大会) and other international events – which were efforts, according to a later history of external propaganda, to publicize the Chinese revolution. Another early effort was the magazine Youth (少年), a communist publication founded overseas in the face of press restrictions from Chiang Kai-shek’s ruling Kuomintang party.

During the Yan’an period (1935-1947) as the Chinese Communist Party established a more permanent revolutionary base in the northern province of Shaanxi, external propaganda was about publicizing the idea of “red China” and mythologizing the great feats of the CCP and the Red Army. Among other writings, the National Monthly (全民月刊), a communist periodical published in Paris in 1936, included an account by Chen Yun (陈云), written while overseas, of the Red Army’s Long March, as the party sought to “expose Chiang Kai-shek’s lie that the Red Army had been defeated and that only a handful of men were ‘on the run.’” As the Second Sino-Japanese War went into full swing from 1937, the Party used various means to propagate the Red Army’s role in the resistance against the invading Japanese. This included the translation of Mao Zedong’s pamphlet On Protracted War (论持久战), published in 1938.

In this period, the CCP’s internal infrastructure for external propaganda began to take shape. By May 1938, the Yangtze River Bureau of the CCP Central Committee (中共中央长江局) had established an “international propaganda committee” (国际宣传委员会) and an “international propaganda group” (国际宣传组) to translate and publish the writings of the top Party leaders, and contribute articles for international publications. The following October, the Southern Bureau of the CCP Central Committee (中共中央南方局) began working with international news agencies to provide news copy about the war that was then distributed through Chinese-language newspapers in Hong Kong and overseas. In early 1939, the Southern Bureau formally launched its “External Propaganda Small Group” (对外宣传小组).

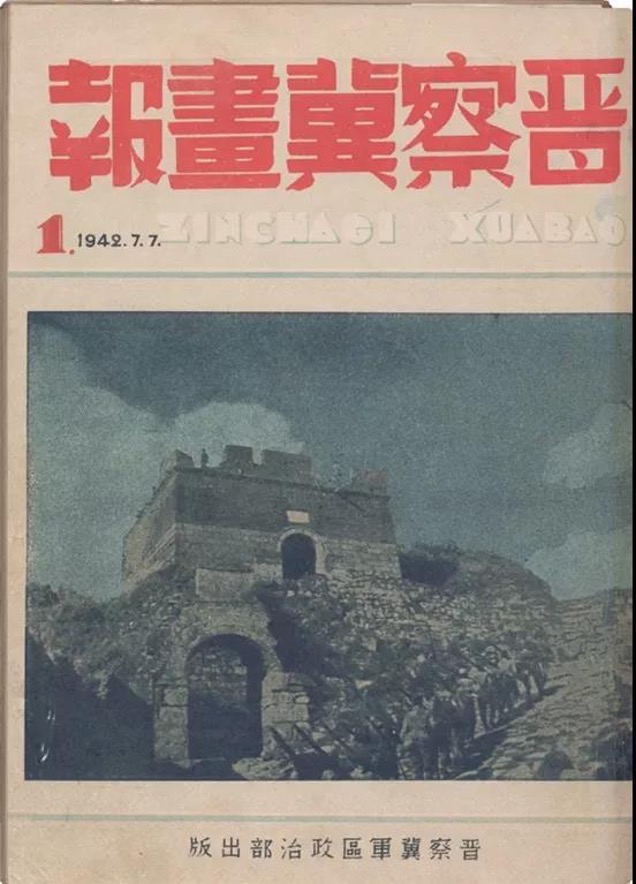

By the 1940s, the CCP’s external propaganda efforts had settled into a rhythm. Publications like China Monthly (中国通讯), published in Yan’an in English, French and Russian, sought to win international support for the efforts of the Red Army. Another publication, the Jinchaji Pictorial (晋察冀画报), was launched in July 1942 in the Jin-Cha-Ji Border Region, a communist controlled area including parts of present-day Shanxi, Hebei and Inner Mongolia. This was followed in May 1943 by the English-language Jinchaji Magazine (晋察冀杂志).

By the mid-1940s, Mao Zedong and other leaders in Yan’an were regularly receiving outside guests, sharing the story of the Party and its ambitions for China. In 1944, this included a reporting trip by a group of foreign and Chinese journalists, as well as a visit by American military officials. In a report passed along to their military visitors and the US State Department, the CCP insisted, according to an account in Party Construction (党建) magazine, that “the Communist Party must be regarded as a continuing and significant and influential force in China under all circumstances.”

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, as the CCP consolidated its domestic press controls under the party’s propaganda department, internal and external messaging was carried out under the principle of “distinction between inside and outside” (内外有别) — an understanding that audiences in and outside of China are fundamentally unalike. That meant foreign propaganda had to adapt to some extent to foreigners’ various cultures, habits, and languages.

An early example of a publication doing just this is China Reconstructs (中国建设), which was founded in 1951 by Soong Ch’ing-ling (宋庆龄), the third wife of Chinese “revolutionist” Sun Yat-sen, to “introduce China to the world and promote peace.” To help in launching the magazine, Soong invited Polish-born journalist Israel Epstein (伊斯雷爾·艾普斯坦) to return to China to take part in the venture. Renamed China Today (今日中国) in 1990, the publication remains an important vehicle for China’s external propaganda, particularly over more sensitive issues of sovereignty and territorial integrity, and it frequently (like other state media) uses foreign voices to support state narratives.

The Early Reform Era

Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening policy marked a period of renewed engagement with the world for China and its ruling party. One development early on was the launch in June 1981 of China Daily, a newspaper published in English (and eventually other languages) after the style of Western papers, and with the express purpose of communicating China’s official views to international audiences. The paper’s website, launched in 1995, was among the country’s first.

Amid broader changes that gripped China’s news culture in the 1980s, the China Daily showed some attempt at experimentation with other approaches, as well as differentiation for global audiences – an approach to the internal/external dynamic that evolved and struggled over the decades that followed. In 1990, the Central Committee of the CCP issued its Circular on Strengthening and Improving Foreign Propaganda, which stressed that external propaganda should be undertaken with more careful consideration of the characteristics of different countries and regions. Publications and other channels should be more targeted, particularly to reach foreign elites. During this period, strengthening relevance became the focus of the “differentiation between inside and outside” principle, and the analysis of foreign audiences became more detailed and targeted. The results, however, remained limited.

Before China’s engagement with the outside world expanded through the 1980s and 1990s, and before the advent of the internet, keeping the internal and external propaganda streams separate — a practice known as “internal and external control” (内外管控) — was relatively simple. Domestic radio and television were only broadcast domestically, and international publications were only distributed internationally. A borderless, worldwide information space presented an unprecedented challenge. Tellingly, however, China dealt initially with the internet as a foreign entity, placing its control from the late 1990s through the 2000s within the Information Office at the State Council, an office dedicated to external matters.

Though some Chinese communications scholars suggested by the 2000s that it was no longer meaningful to distinguish between “internal and external” — that the internet age had created conditions that demanded “internal and external integration” (内外一体)—the divide persisted, compounded as a practical and technological fact by the existence of the Great Firewall.

Hardening Approaches to Soft Power

By the late 2000s, even as China’s economic and military strength grew, its leaders felt that a key area of weakness remained the country’s inability to influence global agendas. In his political report to the 17th National Congress of the CCP in 2007, the party’s general secretary, Hu Jintao (胡锦涛) mentioned “soft power” (软实力) for the first time in an official CCP document. The idea, drawing on the concept by Joseph Nye, was that culture was a necessary reserve of national strength. “In this day and age, culture is becoming an important source of national cohesion and creativity, an important factor in the competition for comprehensive national power,” said Hu. He urged more robust measures to “improve the country’s cultural soft power.” The goal was to build up China’s “international discourse power” (国际话语权), which the leadership saw as key to its comprehensive national power (CNP). And the means to accomplish this, said Hu, was to “innovate the ways and means of external propaganda.”

Hu Jintao urged more robust measures to “improve the country’s cultural soft power.”

During the Hu Jintao era, the goal of enhancing “international discourse power” came with a concerted push abroad by state-run media, including China Daily, Xinhua News Agency, China Central Television, and others – a process often referred to as media “going out” (走出去). Despite substantial investment in the global presence of state media, however, China made few real inroads, and by late 2012, as Xi Jinping came to power, the leadership’s sense of the urgency of its soft power project came to be tied up more closely with the notion of its victimhood at the hands of the West.

According to a narrative that had some currency among scholars in the late 2000s, but became party orthodoxy under Xi, China continued to suffer from what was dubbed the “third affliction.” By building up its military might under Mao and developing the economy under Deng Xiaoping, the country had shrugged off the first of its three afflictions — weakness and poverty — but it continued to be demonized and spoken over by hateful and fearful Western nations.

As he assumed power, Xi Jinping cast himself as the man to beat the affliction of international stigma. Less than one year into his first term, during an internal meeting of top propaganda officials in August 2013, Xi outlined his plan to bring China’s “discourse power” on par with its newfound economic and military might:

There are still numerous misunderstandings about us. Western countries continue to belittle China. The state of international public opinion is determined by the belief that “the West is strong and China is weak.” Western mainstream media still control global opinion; we often find it challenging to make our case or have our voice heard. This issue requires significant effort to resolve. We must focus on advancing our international communication capabilities, innovating our foreign publicity methods, strengthening our discourse system, and striving to create new concepts, categories, and expressions that are understandable both domestically and internationally. We must tell China’s story well, spread China’s voice effectively, and enhance our discourse power internationally.

In his address, Xi Jinping reframed the methods of external propaganda around the idea of “telling China’s story well and effectively broadcasting China’s voice” (“讲好中国故事, 传播好中国声音”). Xi’s approach essentially broadened the concept of external propaganda as a whole-society endeavor. As propaganda officials elaborated the concept in the official communication journal The Press (新闻战线), published by the People’s Daily, telling China’s story well required “the whole party to tell it, all the people to tell it, and to tell it again and again.”

Under Xi Jinping, external propaganda is no longer the work of the central leadership alone. Universities have set up working groups on external propaganda and official outlets catalog their successes in annual responsibility reports. As CMP’s research has shown over the past few years, new “international communication centers” (国际传播中心) at the provincial and municipal levels have also been founded up and down the country, leveraging local expertise and resources to “tell China’s story well” to various target audiences abroad. Part of Xi’s much-touted “innovation” of external propaganda has meant the digitalization of media production across the country (“media convergence”), ensuring that media under CCP control are flexible and ready to exploit new digital tools and reach audiences more effectively — through both domestic and international channels.

The transformation of China’s information landscape, and the global nature of digital communication, has has increasingly eroded the distinction between inside and outside on which the CCP’s external propaganda has long been premised. China’s propaganda system has responded unevenly, both recognizing the importance of remaining relevant, current and flexible on the one hand, and of adhering to centralized approaches to control and production. One commentary in the party’s official People’s Daily called the inside-out distinction “the paradigm will continue to guide China’s foreign communications,” but admitted that the internet and globalization had “challenged” traditional ways of thinking about propaganda.

Bertie Lyhne-Gold

The CMP Dictionary

C

D

F

G

M

N

P

S

- Scaling the Wall

- Science

- Second-Generation Reds

- Security

- Seeking Progress in Stability

- Seeking Truth From Facts

- Self-Revolution

- Seven Bottom Lines

- Six Adheres

- Smart Governance

- Sneaky Visit

- So-Called

- Socialite

- Soft Resistance

- Soul and Root

- Soundless Saturation / Quietly Nourishing

- Sovereignty

- Speaking Politics

- Streamlining Services

- Strong Cyber Power