Mao Zedong and Liu Shaoqi greet a returning delegation overseas led by Zhou Enlai in 1964. Image available at Wikimedia Commons under CC license.

In the Soviet Union and elsewhere in the communist world, the term “proletarian revolutionaries” generally referred to important leaders of the Party and government who emerged at the end of the 19th century and early 20th century as proponents of Marxism-Leninism and were engaged in revolutionary work. Use of the term within the CCP was generally high praise of political leaders at home and abroad as well as key thinkers such as Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Rarely used today, the term was applied briefly to Xi Jinping in 2020, but was soon deleted.

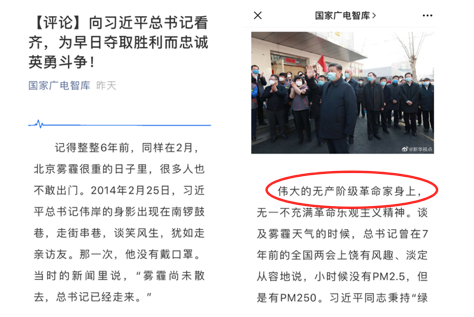

In February 2020, as the Covid-19 epidemic was raging in China, the official WeChat account of the National Radio and Television Administration (NRTA), the ministry-level agency that administers the television and radio industries, made a post in which is lauded the CCP’s general secretary, Xi Jinping, as a “proletarian revolutionary” (无产阶级革命家). The post was headlined: “Following the Example of General Secretary Xi Jinping, For a Loyal and Heroic Struggle for Early Victory.”

The post began by talking about an event in February 2014, when Xi Jinping’s “imposing figure” appeared in Nanluoguxiang, a well-known alley in Beijing, at a time when dangerously smoggy air was a hot topic across the country. The stunt was meant to signal to the public at the time that their leader was human and accessible, ready to breathe the same air. The February 2020 post read: “He did not wear a face mask that time. The news at the time said, ‘The smog has not dissipated, but the general secretary has already emerged.’”

The post included a photo of Xi Jinping wearing a face mask during a tour of a Beijing neighborhood on Monday, part of a series of visits meant to show that he was present on the front lines of the fight against the coronavirus. The reference to Xi as a “great proletarian revolutionary” came a bit further down in the post: “Great proletarian revolutionaries are always filled to the brim with the optimistic revolutionary spirit.”

Since the People’s Daily newspaper was launched on May 15, 1946, 40 people have been described in this way, which may seem to suggest the term is not so exceptional. However, it should be noted that aside from Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, all of those mentioned as “proletarian revolutionaries” were labelled as such only after their deaths, and often in official obituaries. It is exceptional to be designated a “proletarian revolutionary” during one’s lifetime.

The label was used early on and with some regularity for Mao Zedong, accounting for the majority of instances we find in the People’s Daily. For Deng Xiaoping, the title came only after his resignation as chairman of the Central Military Commission in 1989.

As for the others, here is a taste of the distinguished group:

Karl Marx

Friedrich Engels

Former Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin

Former Soviet leader Josef Stalin

Former Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito

The novelist Lu Xun

Revolutionary-era figures Peng Pai, Fang Zhimin and Chen Tanqiu

German Communist Party founder Rosa Luxemburg

Liu Shaoqi

Zhou Enlai

Zhu De

Li Xiannian

Zhang Wentian

Ye Jianying

Peng Zhen

Deng Yingchao (a rare woman on the list)

Hu Yaobang

The group also includes Xi Jinping’s father, Xi Zhongxun, who after his death was praised as an “excellent proletarian revolutionary” (杰出的无产阶级革命家). But the reference to Xi Jinping as a “great proletarian revolutionary” faced a quick death online. The post was removed within 24 hours, yielding the following error notice reading: “This message is not viewable as it violates regulations.”

This was an interesting turn of events, that a post made to WeChat by one of the chief regulators in the information terrain, the NRTA, should be deemed so quickly in violation of regulations. According to its public description, the account, “National Radio and Television Archive” (国家广电智库) is operated by the Development Research Center of the National Radio and Television Administration” (国家广播电视总局发展研究中心), and works to “explain policies in the radio and television sector in a timely manner, posting leadership speeches, industry news, development plans, radio and television laws and regulations, research reports and so on.” In this case, the account’s praise for Xi Jinping perhaps went too far. It might also have been regarded as an embarrassing case of “high sarcasm,” or gaojihei (高级黑), damning through the act of praise.

CMP Staff

The CMP Dictionary

C

D

F

G

M

N

P

S

- Scaling the Wall

- Science

- Second-Generation Reds

- Security

- Seeking Progress in Stability

- Seeking Truth From Facts

- Self-Revolution

- Seven Bottom Lines

- Six Adheres

- Smart Governance

- Sneaky Visit

- So-Called

- Socialite

- Soft Resistance

- Soul and Root

- Soundless Saturation / Quietly Nourishing

- Sovereignty

- Speaking Politics

- Streamlining Services

- Strong Cyber Power