Xi Jinping arrives with his wife, Peng Liyuan, to attend the G20 meeting in Argentina in November 2018. Image from G20 Argentina available at Flickr.com under CC license.

It was during the CCP’s first ideological mass movement from 1942 to 1945, as Mao Zedong purged his opposition and secured his leadership of the Party, that the idea of the “leadership core” (领导核心) was first advanced in China. In the midst of the Yan’an Rectification Movement, the Party held a leadership conference extending over 88 days from October 18, 1942, to January 14, 1943. During the conference, Mao delivered a number of speeches in which he reviewed Joseph Stalin’s 1925 interview The Prospects of the Communist Party of Germany and the Question of Bolshevisation, in which the Soviet leader had discussed “the question of the leading cadres.”

It was during these speeches that Mao introduced the notion of the “leadership core,” a not-so-veiled assertion of the necessity of his own strong hand at the top. In one speech, Mao said:

All units must give priority to the building of the leadership core. Without a core, things cannot be done, and no everyone is the leadership core. Without a leadership core, how can there be leadership? The leadership core emerges from the midst of struggle . . . .

The struggle within the Party during those years indeed secured Mao Zedong as the Party’s unquestioned core. It ultimately brought the death of thousands of intellectuals and shaped a cult of personality around Mao that would stand through to the end of the Cultural Revolution.

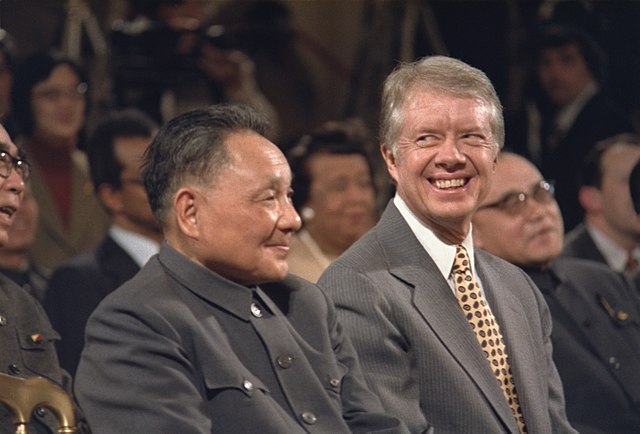

The “Core” in the Era of Reform

In the first years of China’s reform and opening policy after 1978, as Deng Xiaoping set the country on a new path of economic development and opening to the outside world, he criticized the “errors” made during the previous decades, and there was some effort in particular to motivate against the over-concentration of power. Despite being twice purged by Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping did not censure Mao personally for the Cultural Revolution and other catastrophic excesses. Instead, he located the problem in the political system: “Over-concentration of power is liable to give rise to arbitrary rule by individuals at the expense of collective leadership,” he said.

Nevertheless, Deng’s position at the top of the CCP leadership had to be secured in order to focus consensus within the Party and push through his reform and opening policy. It was the Central Advisory Commission (中央顾问委员会), or “CAC,” a high-level body established following the 12th National Congress of the CCP in 1982 to advise the Central Committee, that designated Deng as “the core of the second-generation collective leadership” (第二代中央领导集体的核心). The powerful body, which stood even above the Politburo Standing Committee during this period, was comprised only of CCP officials who had served more than 40 years. It was this “core status” (核心地位) conferred on Deng by the Commission that sealed his position as paramount leader.

Among the Commission members was another leading proponent of reform, Chen Yun (陈云). Like the others, he supported Deng’s “core status.” But he also supported the abolishing the lifetime tenure for serving officials, a step seen as essential to avoiding over-concentration of power like that seen in the Mao era.

In the wake of the brutal crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrations across China in June 1989, and the ouster of Premier Zhao Ziyang (赵紫阳), it was Shanghai leader Jiang Zemin (江泽民) who was brought in restore order and be the new front-man with the backing and blessing of Deng Xiaoping. Deng called on the Party to support Jiang as the “core” of the central CCP leadership (以江泽民同志为核心的党中央) to guide China through a new and difficult phase of reforms, which were initially threatened by the resurgence of leftist hardliners within the Party and growing isolation internationally.

Importantly, Jiang Zemin’s status as “the core” was conferred directly by virtue of Deng Xiaoping’s support at a crucial moment following the convulsions brought on by the Tiananmen Massacre. It was not a title Jiang claimed for himself. By the time Jiang’s successor, Hu Jintao (胡锦涛), rose to the position of CCP general secretary at the 16th National Congress in November 2002, Deng had been dead for more than five years, having passed away in February 1997. Hu’s tenure continued what seemed a growing trend toward more collective leadership, parting ways with the more charismatic leadership styles of the past under Mao and then Deng. Hu Jintao was never referred to as the “core” of the CCP leadership, and was generally marked in the official discourse by the rather more literal phrase “the CCP Central Committee with Comrade Hu Jintao as General Secretary (以胡锦涛同志为总书记的党中央).

The “Core” Returns

From the very beginning of his tenure as general secretary in late 2012, Xi Jinping seemed to pursue of more nostalgic path as the Party’s charismatic top leader. He placed himself prominently at the heart of revanchist narratives about historical greatness and the “Chinese dream” (of the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”), fashioning an image of himself as a lovable leader walking in the midst of adoring masses – rather unlike the more technocratic images of Jiang and Hu. From 2014 in particular, Xi’s utterances as the man adoringly referred to as “Uncle Xi” (习大大) were touted a homespun inspirational wisdom in the party-state media, with top lists of pithy quotes in various policy areas.

In the years following, the quasi-cult surrounding Xi Jinping continued to take shape, and it became clear the Xi and his Party publicists were actively emulating the iconography of the Mao era. Even Xi Jinping’s signature as added to books and official propaganda materials was decidedly Maoist in appearance. Just four years into his first tenure as general secretary, Xi Jinping was designated as China’s “core” leader during the 6th Plenary Session of the 18th CCP Central Committee in October 2016. According to reporting by the People’s Daily in 2016, the plenum called on all CCP comrades to “unite around the Central Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping as the core.” This marked the first time Xi was referred to in official CCP discourse – in a high-level publication – as the “core.”

Since 2016, Xi Jinping’s power and prestige within the CCP has continued to advance, and references to him as the “core” have become routine. For example, in an article in the People’s Daily on June 13, 2022, (丁焰章), chairman of the state-run China Power Construction Group, began a commentary on “green development” by saying: “China’s striving to achieve carbon peak by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060 is a major strategic decision made by the CCP Central Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping as the core . . . . “

Stella Chen

The CMP Dictionary

C

D

F

G

M

N

P

S

- Scaling the Wall

- Science

- Second-Generation Reds

- Security

- Seeking Progress in Stability

- Seeking Truth From Facts

- Self-Revolution

- Seven Bottom Lines

- Six Adheres

- Smart Governance

- Sneaky Visit

- So-Called

- Socialite

- Soft Resistance

- Soul and Root

- Soundless Saturation / Quietly Nourishing

- Sovereignty

- Speaking Politics

- Streamlining Services

- Strong Cyber Power