In early July 2024, at one of China’s biggest AI events of the year, a moment of truth arrived to upset an oft-upheld official buzzword — one that had come over several months to represent the country’s world-leading ambitions in the field of artificial intelligence.

The event was the World AI Conference in Shanghai. The buzzword was “The Hundred Model War” (百模大战), the idea that China could lead the global race for AI by encouraging the diverse development of the data-trained machine learning models known as foundation models. The speaker was Robin Li, the CEO of the Chinese tech giant Baidu, a man whose views on tech development tend to command respect.

While Li assured technologists, tech executives and officials at the event that foundational models had allowed China to catch up to the cutting edge of AI, he cautioned there were now too many models — with too few practical uses. “The Hundred Model War has caused a huge waste of resources, especially computing power,” he said.

For such a prominent tech CEO to acknowledge that an oft-upheld official buzzword had downsides was for some a wake-up call.

Beginning in 2023, the phrase “Hundred Model War” has been frequently used by the official Xinhua News Agency, the People’s Daily and other state media as short-hand for the myriad Chinese companies that have released Large Language Models (LLMs) — the deep-learning algorithms that are at the heart of AI — and competed for talent, users and clients as they vie for top ranking in the booming industry. “Hundred Model War” refers essentially to the competitive development of various types of “large-scale deep learning models” in the application domain.

With its reference to hundreds, the phrase invokes dramatic metaphors from CCP history. For some, it conjures up the massive “Hundred Regiments Offensive” (百团大战) of 1940, when the communist National Revolutionary Army under the command of Peng Dehuai joined Nationalist forces against the invading Japanese — and was later praised for acts of courage and sacrifice that were much mythologized.

It even found its way onto a CCTV list of the top 10 buzzwords of 2023, compiled by Xinhua and a government think-tank.

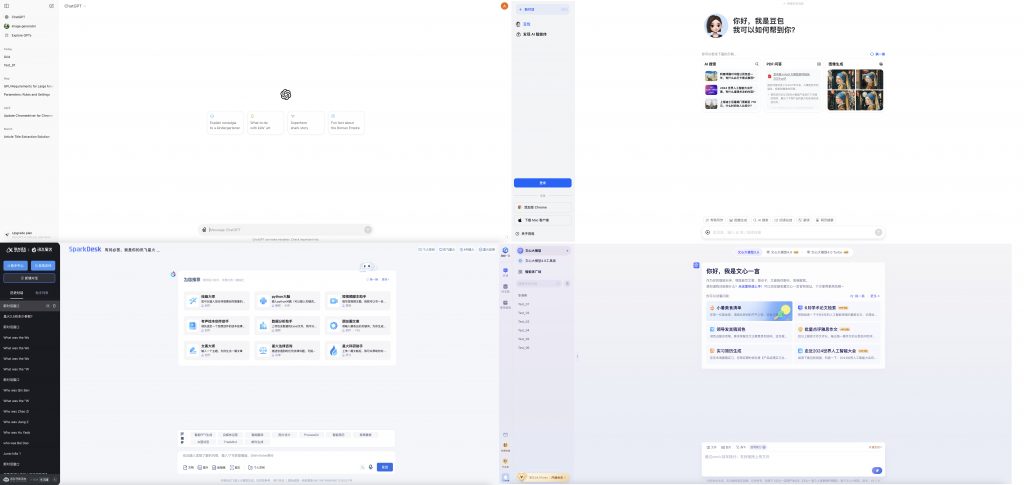

There’s more than a whiff of positive messaging here. The government and the tech industry benefit from the impression — as AI becomes a major development story globally, dominated by companies like OpenAI — that innovative homegrown AI companies are competing aggressively for a large and hungry market. But this battle is carefully coordinated and encouraged by the state, and many of these LLMs resemble OpenAI’s ChatGPT a bit too closely. As Robin Li implied, many may have entered the war for the sake of making a model alone.

Eve of War

There are currently over 300 LLMs in China. However, government statisticians reported in March 2024 that only about 100 of these are substantial enough to compete with ChatGPT. The term “hundred models” also serves as shorthand for the surge of companies entering the AI field in 2023 and 2024. In June 2024, the number of generative algorithms registered by the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) increased twelvefold compared to June of the previous year.

China has been training its foot soldiers for this engagement for a long time. In 2017 the State Council released a development plan, aiming to have an AI ecosystem level-pegging with the best in the world by 2020, and making breakthroughs of their own by 2025. It pledged to cultivate emerging AI business models and encourage existing “large internet companies” to develop key AI software. 2021 saw a dramatic increase in the number of models released in both China and the US, with the pattern continuing in 2022.

But it was the quiet release of ChatGPT on November 30, 2022, and its subsequent popularity with Chinese users, that really pushed businesses into releasing models of their own. Now that a high-quality version of the technology was shown to be possible, it was only a matter of applying it to China’s needs. “Everyone is very clear about one thing, that China must need its own big model,” said one unnamed Chinese AI entrepreneur in March 2023 on the specialist podcast OneMoreAI, one of the earliest mentions in print of the “Hundred Model War.” It seemed clear the ones who made models that could be widely adopted in China would make a fortune.

The phrase emerged among AI developers and entrepreneurs around this time, in reference to the abundance of companies able to enter the area given loose regulatory oversight on AI companies from the government. The idea was that ruthless competition would then winnow numbers down, leaving only the strongest still standing. “This stage will definitely bring a result, that is, ultimately a few [strong models] will come out,” said the entrepreneur.

Models for Models' Sake

Why does the Chinese leadership want to let a hundred models bloom (to appropriate another important "hundred" reference from PRC history)? In October last year the Global Times newspaper, published by the Party’s official People’s Daily, hit the nail on the head, saying the creation of hundreds of models was key to developing China’s AI infrastructure, driving innovation through the use of these models in different industries, an engine pushing the country forwards.

The problem is that many of the hundred models are indeed similar to one another — often trained off the OpenAI technology that spawned ChatGPT, and offering more or less the same applications. Far from innovating, even the web layout for China’s major AI players was an imitation of their US rival's.

In recent months, models have had to start cutting prices as the major way to differentiate themselves from the competition and attract consumers in what has become a highly saturated market.

On July 4 People’s Daily Online argued the field has morphed into a “Hundred Model Price War,” but put a positive spin on it, seeing the competition as evidence of a continued drive towards innovation: “This is not only a game between cost and market, but also a test of the innovation and operation capabilities of enterprises.”

The idea that this is a “war” makes it sound as though innovation was abundant and the market was becoming a crucible, burning away all but the highest-quality contenders. Yet the number of true innovators is small, with many companies launching models merely to look like they're meeting current political demands. “With all the industry summits talking about embracing AI, people will form the logic that if I don’t do it, it will look like I’m not very active,” another unnamed Chinese AI entrepreneur told Initium Media this month.

Alex Colville

The CMP Dictionary

C

D

F

G

M

N

P

S

- Scaling the Wall

- Science

- Second-Generation Reds

- Security

- Seeking Progress in Stability

- Seeking Truth From Facts

- Self-Revolution

- Seven Bottom Lines

- Six Adheres

- Smart Governance

- Sneaky Visit

- So-Called

- Socialite

- Soft Resistance

- Soul and Root

- Soundless Saturation / Quietly Nourishing

- Sovereignty

- Speaking Politics

- Streamlining Services

- Strong Cyber Power