Headlines and Hashtags

On the "historic" list of delegates in People's Daily and other signposts of inner-party democratization

As October’s 17th National Congress draws closer, the word “democracy” (and its numerous permutations) is being tossed around like a hot potato in China’s media, from official party journals to more liberal commercial papers. Not long ago, an article from Asia Times suggested the late-breaking debate in China over political reform was flash-in-the-pan, “unlikely to last much longer.” But how much of the “democracy” talk inside China is really substantive, and how much can be dismissed as posturing, pandering and doublespeak? [IMAGE: News coverage of “inner-party democracy” begins in November 2006/frontpage of Jinghua Times announcing increase in “differential rate” (see below)].

An article by Liu Junning (刘军宁), a Chinese reform scholar who has often fallen afoul of propaganda authorities, argued earlier this summer that the “fact that ‘political institution reform’ [政治体制改革] has become a widely-accepted term reflects that the ruling party and the public have reached a consensus, the only consensus ever, that political reform is highly necessary.”

One can of course wonder about how deep that consensus runs, but Liu’s general point, that the notion of “political institution reform” — alternatively translated “political reform” — has gained some traction in recent years, is spot on. As Liu points out, however, the term that really seems to be gaining momentum is “inner-party democracy” (党内民主), and in China the devil is in the details of terminology.

The general upward trend of “inner-party democracy” is moderate but sure when we plot the term’s use in China’s media generally. The trend is much more prominent when we isolate official party publications. Study Times, for example, is a journal published by the Central Party School, where much of the party’s thinking and strategizing about political reform happens. The following graph plots articles in the journal that make primary use of particular political reform terms (measured by appearance of these terms in headlines):

It is important to recognize that there are many words to describe the process of political reform in China, some solidly “party”, others neutral, still others redolent of Western-style constitutional democracy (and therefore regarded with caution by party leaders). The term “political institution reforms”, or zhengzhi tizhi gaige (政治体制改革), is a more neutral term, the preference for which, according to CMP analysis, has marginally declined over the last few years.

Another term in the graph above is “political civilization” (政治文明), a creation of former President Jiang Zemin, and essentially “political reform” shrouded in a noncommital fog. The term has, not so surprisingly, plummeted during the Hu Jintao era.

The term “inner-party democracy”, an old term that has blown hot and cold in the past, is quite clearly on the rise under Hu. And much of the buzz about “political reform” in China’s media lately has been about “inner-party democracy.”

A Chinese government white paper on “democratic rule” by Chinese Communist Party (CPC) following the Fourth Plenum of the 16th CPC Central Committee in September 2004 said that “promoting people’s democracy by improving inner-Party democracy” was “an important component of the CPC’s democratic rule.” The basic idea of “inner-party democracy,” as reflected in this paper and other official documents, is about “making efforts to establish and improve a mechanism to guarantee the democratic rights of Party members.” That is, allowing party members a more equal say in decision making on policy, appointments, etcetera.

The term sounds unavoidably slippery to anyone who hopes and supposes China can achieve multi-party democracy without passing GO. But there are interesting — if not quite earth-shattering — things happening under the aegis of “inner-party democracy.”

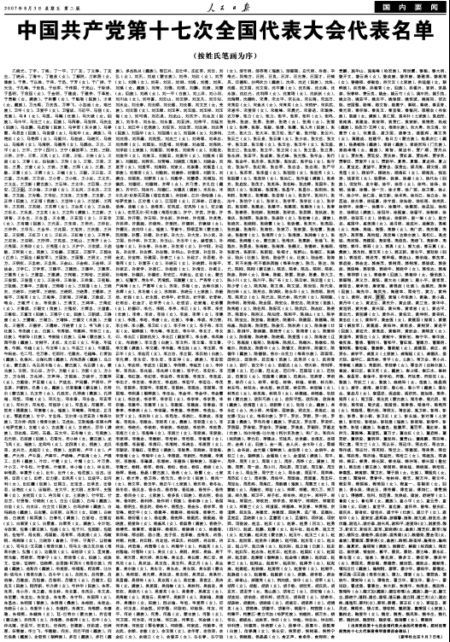

When a list of all 2,217 delegates to the 17th National Congress was made public through newspapers across the country on August 2 [See image below], this received little or no attention outside China. And yet, nodding to the usual need for caveats and potent scepticism, this clearly was a historic first for China.

The list, which appeared in full on page two of People’s Daily, was announced with a headline at the top of the official paper’s front page.

Quoted at Southern Weekend, in one of few domestic news reports to tease out the importance of the candidate list, the director of the History Division of the Central Party School, professor Wang Guixiu (王贵秀), noted this was the first time a list of delegates to the National Congress had been published prior to a session.

Analysts said the move demonstrated the party’s increased attention to public opinion and public feeling. “Before, candidacy was limited to those within the party [SEE People’s Daily coverage] and announced [only] within limited circles,” said one veteran expert on party building at the Central Party School, quoted by Southern Weekend.

Another scholar, Xie Chuntao (谢春涛), said publication of the list meant drawing in the participation of the people in order to better monitor delegates.

But wait a minute. If the public were never involved in nominating or electing these delegates in the first place, what does this sort of “inner-party democracy” have to do with public opinion and feeling?

In the glass-half-full reading of the People’s Daily list (to which CMP does not necessarily subscribe) , this is important because democracy (insofar as it is a process) doesn’t necessarily mean a summary mandate for direct public election of delegates. The publishing of this list injects a tiny but, some would say, unprecedented degree of transparency into the process of the National Congress by allowing a window of opportunity for “participation” through China’s very imperfect court of public opinion.

Yes, the media are controlled by authorities wielding the mandate of “correct guidance of public opinion”. Yes, the people have limited channels to express their views. The idea, nevertheless, is that party officials might begin to hear, between now and the National Congress, the whisperings of unfavorable opinion about delegates now so publicly on the list.

This step toward more transparency and participation within the party structure, and more feedback from society at large, may seem like a silly half-measure from the outside. But it’s more than probable, given the prevalence of corruption in the party’s ranks, that some National Congress delegates are jittery about the People’s Daily list and take it very seriously. One thing to watch between now and October is whether any particular delegate on that list becomes the target of scrutiny from discipline inspection officials.

Other milestones of “inner-party democracy” that have drawn attention from domestic Chinese media this year are the “election” of delegates from a broader segment of Chinese society [See People’s Daily coverage], and the selection of delegates from a larger pool of “candidates” than was the case for the 16th National Congress.

The latter rather esoteric measure refers to the “differential rate” (差额), or cha’e, the ratio between delegates nominated by party standing committees at various levels to the total number of National Congress seats available.

For appointment of delegates to the upcoming 17th National Congress, there was reportedly a five percentage point rise in the differential rate, 15 percent as opposed to 10 percent, from the 16th National Congress back in 2002. That means, basically, that for every 100 seats available for this year’s congress, an additional 15 nominees were chosen (by party committees at various levels) and eventually pared down by party members (any who chose to vote) at those levels.

The list of 2,217 delegates published in People’s Daily represents the results after 15 percent of nominees were removed in the differential rate process (被”差”掉), which means they were pared down from an initial pool of around 2,550 nominees. (Domestic coverage of the increase in the differential rate for the 17th National Congress, courtesy of Xinhua News Service, appeared back on November 13, 2006, suggesting selection of the final list of delegates occurred sometime shortly after that date.)

How significant are those numbers? At this point, they are more symbolic than anything else. Consider that with 30 provinces and autonomous regions in China, there are just over 300 differential candidates, or an average of around 11 per province. That means that in the vast majority of voting districts (county or city, etc.) there are no additional candidates. While party members are theoretically tasked with “electing” their delegates, there are in most cases no decisions to be made.

That doesn’t mean the differential rate is worthless as a measure of political liberalization in China. As Southern Weekend noted indirectly in its recent analysis of the delegate selection process, the rate was higher than at present, over 20 percent, during the relatively liberal Zhao Ziyang era leading up to democracy protests in Beijing in 1989.

Conclusions? We’ll just have to wait and see what changes, however incremental, the upcoming CPC congress brings. But as unappetizing as the concept of “inner-party democracy” may seem, this is a process anyone interested in political reform in China will need to watch closely and seriously.

MORE SOURCES:

“China’s quest for political reform: intra-Party democracy or constitutional democracy?“, China Elections and Governance, June 23, 2007

“China’s inner-party democracy: toward a system of ‘one party, two factions’?“, The Jamestown Foundation, December 6, 2006

“Important measures for developing inner Party democracy and safeguarding Party members’ rights“, People’s Daily, October 26, 2004

[Posted by David Bandurski, August 14, 2007, 11:32am]