By Qian Gang — It is no petty crime in China to be accused of setting up an “illegal organization.” Last month, the organization “Gongmeng,” a group of rights defense lawyers that had not obtained legal registration, was branded an “illegal organization,” and its Gongmeng Legal Research Center was raided and closed down.

At the end of April, the Wenzhou Business Club of the Dongguan General Chamber of Commerce in Guangzhou was ruled an “illegal organization” “daring to carry out activities” in the name of a social group, and was ordered to cease all operations. Some time before this, authorities in Guangzhou said taxi drivers who organized a general strike late last year under the auspices of a “collective tea time” (集体喝茶), “[in fact] had illegal organizations working behind the scenes.”

Under strict censorship controls, the vast majority of Chinese journalists are suffocated with a silent fury over such trumped up allegations. But this week instead we’ve seen the opposite — media aggressively opening fire on a so-called “illegal organization.”

On August 26, the Beijing News reported that Zhao Yang (赵阳), a member of the City Administrative Department of Nanjing’s Xuanwu District – this is the office that runs the local brigades of non-police ‘city inspectors’ charged with keeping public order in China’s urban neighborhoods – had been charged with organizing an online “national joint session of city administrative department heads.” Zhao had dared to hold an event without proper registration and in the name of a social group, so this amounted to the act of “illegal organization.”

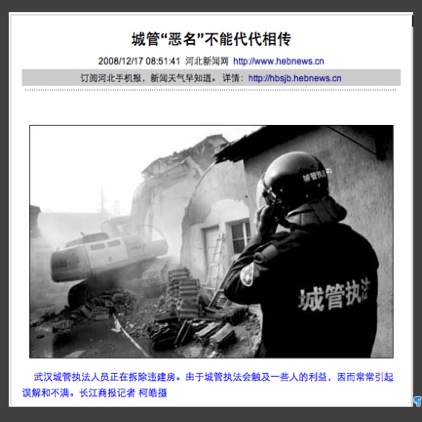

[ABOVE: Do city inspectors need their own guild? Screenshot of coverage at Hebei News Online of city inspectors overseeing the demolition of “illegal” housing in Hebei.]

The reporter following up on the story came across this organization’s statutes. They discovered that the organization had a founding chairman, an honorary chairman, a rotating chairmanship, a managing director, a deputy director, an executive council and so on. It had set up an administrative headquarters, and even had a membership fee system in place. It had already held three national conferences, had issued awards and conferred titles. It had decided on national standards for city inspector identification. For all intents and purposes, it was the national guild for city inspectors in China.

The report caused an uproar. For the authorities to see “illegal organizations” as thorns in their side, that was one thing. But it seemed like a great big joke for government officials like city administrative department heads to be participating in such organizations. The media followed up on the story and found that the organization behind these joint sessions was in fact a private company, which was scooping up all of the funds. A private company boss, in other words, had been toying with city administrative department heads across the country, offering public relations and crisis management services to address the poor public image of city inspectors.

Like a rat scurrying through a busy market, this organization of city inspectors was suddenly the target of unmitigated attacks. Between August 26 and September 3, over just nine days, 353 reports appeared on the Internet (returned in a Baidu search of the terms “city administration heads” and “illegal organization”). Of these, 56 were re-postings of the original Beijing News story. People were up in arms about many different things, including how various local governments could be using taxpayer money to support such an organization.

One Web user at the popular portal QQ.com summed the case up in a snide imitation of the divisive CCP jargon generally used in the event of social unrest:

This is all about ‘people ignorant of the situation’ and ‘at the instigation of a few elements’ daring to take part in ‘illegal organizations.’ As for participation in ‘illegal organizations’ by city inspection heads, we can only say that they were ‘controlled by people with ulterior motives.’

Journalist Guo Yukuan (郭宇宽) wrote in Huashang Bao that the charges made against this “national joint session” were identical to those made against Gongmeng and its founder, Xu Zhiyong: “First of all, it did not register with the Ministry of Civil Affairs. Secondly, it definitely did not have credentials as a public charity organization. So regardless of whether the units involved gave money and participated voluntarily, the founders fall under suspicion of tax evasion for perhaps not having reported taxes to the tax authorities.”

Guo Yukuan (郭宇宽) continues:

Some people will say, if they’re not doing anything illegal, why didn’t they just go and register? But you have to understand that in China the registration process is incredibly troublesome. To register a non-profit organization, you must find a government office or other institution (事业单位) willing to back you up …. And if you want to register as a company, well, then there are substantial tax burdens involved, and setting up an office, even if you don’t have a cent of income, can require tens of thousands of yuan. Who could possibly play such a game? And for all that, you are still not allowed to do activities in the name of a public charity organization . . . We need to think about the fact that it is this excess control that has created this situation in which all over the country we have these ‘illegal organizations’ ‘daring to hold activities.’

China’s media, which are still strictly controlled, must keep quiet about many things that would infuriate the public if known. Like trees abiding in the cracks of a sheer cliff face, they grow twisted. They make only glancing and oblique attacks against the hovering mass of authoritarian power.

Unable to issue direct calls for the relaxation of controls on civic groups in China, the media have paid back in the same coin, viciously attacking the “national joint session of city administrative department heads,” an “illegal organization” bringing private and official business together in an unsavory alliance.

Citizens and media in China have numerous “soft opposition” (软抗争) tactics at their disposal. There is “pretending to be deaf and dumb” (装聋作哑), for example, when journalists hear thunder but act as though they had no idea a storm was coming. The Chinese edition of Esquire had to know last month that Gongmeng was in trouble, and yet they used the small window of opportunity in which the government had not yet fully shut Xu Zhiyong’s mouth, promoting him to the magazine’s cover.

Then there are “word games” (文字游戏), as when Web users criticized Hu Jintao’s policy of “harmony” (a.k.a., censorship) on the Internet by making a cottage industry out of a humorous synonym, “river crab.”

There is the “fresh flower with thorns” (鲜花带刺), writing in a panegyric style what is essentially a critical report – as when media reported on a Hope School that did not collapse in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake as a way of drawing attention to the problem of shoddy school construction.

These tactics of opposition are necessitated by a society that is basically unwell. Chinese media have no other choice but to carry out a low-grade guerrilla war with authoritarian power. Of course we are eager for a time when criticism is afforded dignity, a time of open and rational debate, a time when the ordinary monitoring of power is possible and acceptable. But that time can only come in China when freedom of expression is respected.

[Posted by David Bandurski, September 4, 2009, 12:36pm HK]