Since July this year there have been rumblings of change in the world of the Chinese microblog, hints that authorities are getting more active in the control of this new information medium, which allows virtual real-time sharing of information tidbits among networks of users. Last month, CMP fellow and new media expert Hu Yong (胡泳) wrote of the importance of the microblog in China. Hu’s delicate subtext was that new attempts to control the technology must not be allowed to sap it of its vitality.

The signs, it seems, are now becoming more explicit.

In a blog entry posted yesterday, Wu Danhong (吴丹红), an assistant professor at China University of Political Science and Law, who writes online under the alias “Wu Fatian” (吴法天), popped the lid on the recent death of his microblog and the censorship he endured while maintaining it over a period of five months.

Wu Danhong is perhaps best known outside legal circles in China as the man who uncovered the truth about Chinese businessman Yu Jinyong (禹晋永), who was found to have falsified his resume, and was one of a number of prominent Chinese business leaders this summer to be dragged through the muck of the Internet. Here, for example, is a recent interview (in Chinese) in which Wu Danhong talks about how he first began to suspect that Yu Jinyong had lied about his education and credentials.

For those who missed the fireworks, New Century magazine has a good run down in English of the scandals facing Yu Jinyong and others recently.

Incidentally, it was also Yu Jinyong who famously thrashed the media as the source of his troubles, saying during a press conference he called: “If I want to close the door and beat the dogs, I have to first let them into the house. So there are a lot of media with us today.”

The following is Wu Danhong’s post yesterday on the senseless murder of his microblog.

Many people already know who I am — at least since I openly exposed the frauds of Xu Jinyong. But this is only a small part of my world. I have spent fifteen years studying the law, and I have been on the Internet for twelve years already. The Internet has become an important space in which I share my ideas about rule of law.

In the past, I was quite preoccupied with my academic work, a young scholar who scarcely lifted his head to see what was happening in the real world. Every year I wrote academic papers, and only every so often did I write more casual essays. Letters from two death-row inmates ultimately shook me out of my quiet and complacent life.

Both inmates wrote to me after reading editorials I had written for the Legal Daily and the Procuratorate Daily. They described the wrongful aspects of their cases and hoped that I could offer my assistance. I was unable to help them, but their appeals did make me recognize that legal scholars had an obligation to share their knowledge and ideas with society at large, and that perhaps this is a far more important business than the writing of academic papers. Here is how I put it in the preface to Profiles in the Law:

In academia, should we or should we not turn our attention more to real and living things of concern? Indeed, the bulk of our academic work is shared within the community of legal scholarship. But commentaries and editorials can reach a much larger audience, helping more people understand the concepts of democracy and rule of law, and giving them an experience of fairness, justice and conscience.

Ever since I began practicing law part time and writing a blog in 2005, my writings have circled around one idea, or one hope — “that one day those who observe the law will not be alone and isolated, that those who break the law will live in fear, that the law enforcement process can promise fair trials and give us a society in which justice prevails.”

It was by happenstance that I registered on Sina Microblog on April 5, 2010, and began my days as a microblogger. As a Web-based information tool allowing rapid connection with groups of people through bits of information, the microblog allows great ease of communication.

But my optimism about microblogging came with underlying reservations too. Back in April I wrote on my microblog: “The rise of the microblog has revolutionary significance for freedom of speech in China. On this platform through which everyone can become a ‘journalist,’ information controls are already rendered powerless, and hundreds of millions of Internet users are pushing their way into the future through a society that has already become rotten. Perhaps in the not-too-distant future, the communication technology of the microblog will develop and replace traditional media. The biggest unknown factor is when the government will step in to muzzle the power of this wild horse surging forward.“

In fact, controls on the microblog were already evident as I expressed the above sentiment. Another professor at China University of Political Science and Law, Xiao Han (萧瀚), a colleague of mine and someone who dares to speak the truth openly, had already been “reincarnated” some thirty times — he would move his microblog to another account for a while before that one would be shut down. But for those users registering accounts in their real names, there had not yet been a precedent in which a microblog was completely shut down.

August 28 marked the one-year anniversary of the launch of Sina Microblog. To commemorate the day, I wrote a record of my experiences with my Sina Microblog being blocked and deleted. My intention was to gift Sina with a certificate of merit, or a silk banner of honor, if you will, thanking their management personnel for their arduous work in deleting posts and blocking service, for their contributions toward a harmonious society. But this pleasantry of mine ultimately unleashed the pent-up displeasure these management personnel felt towards me. Without any prior notice whatsoever, the posting function on my microblog was made subject to item-by-item review, and all subsequent posts were blocked.

But it seems this matter was not so simple as it appeared on the surface.

On August 29, after the attack on Fang Chouzi (方舟子), there was quite a stir on the Internet. Many people wondered why I had not responded to express my support for Fang. They had no idea I could no longer make posts.

On August 30, my response and comments functions were set to item-by-item review by management personnel, and I found later that my responses were not being posted at all. I was entirely unable to respond or comment.

On August 31, my personal photograph and bio were deleted by Sina Microblog management personnel, and I received no prior notice whatsoever about this. I attempted to make contact with managers, and one manager told me that this wasn’t their decision, but was “the intention up top” (上面的意思). I said my microblog had contained nothing at all that could be construed as illegal or reactionary. He said my posts had probably dealt too much with current politics (时政内容太多). I said I focused mostly on legal issues, and can you guess what he said? He said, “The law is also current politics.”

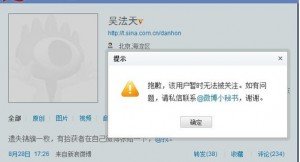

On the night of August 31, I discovered that not only were my microblog followers not growing, but they were in fact falling in number. I watched them fall from 9,958 to 9,952. When I asked my friends about this, they said I had already been marked as “forbidden” (禁止关注), so it was no longer possible for others to follow me. A few of my friends were skeptical. They un-followed me and then attempted to add me again — but this was impossible.

This is how Sina Microblog has managed to thoroughly kill me off. 9,957, 9,956, 9,955 . . . Before long, all of my Sina Microblog followers will vanish.

In the last day or so, I’ve tried many time to get the news out, but all of my posts have been deleted by Web managers. If other microblogs attempt to post my content they too are deleted. A reporter from Youth Times approached Sina Microbog on my behalf and was told that all this was because “large amounts of language attacking the government had been posted” (发表大量攻击政府的言论).

In truth, it’s difficult to find anything among my posts that attacks the government. If they said that I had attacked Tang Su (唐骏), Yu Jinyong (禹晋永), Li Yi (李一) and Dong Siyang (董思阳) then I would have to confess. I’ve spent a great deal of energy exposing their frauds. But do they represent the government?