Still wondering what Xi Jinping’s new buzzword, the Chinese dream, is all about? Well, the Red Flag journal, a sister publication of the CCP’s official Seeking Truth, continues this week with its series on what the Chinese dream IS NOT.

This latest theoretical rant, written by Yu Zhong (喻中), the head of the School of Law at Capital University of Economics and Business, is called, “‘The Chinese Dream’ and the Choosing of a Road to Democratic Politics.” The basic gist of the piece is that constitutionalism — the recent bugbear of China’s leadership — is a notion inferior and subordinate to the Chinese dream.

The logic that equates the Chinese dream with the “dream of constitutionalism” just as the American dream is associated with constitutionalism, says Yu, is “far too much of an oversimplification.”

Of course, he conveniently ignores the fact that few, if any, inside China who are talking about the issue of constitutionalism are talking about imitating the United States (Just read one of the articles originating the idea of “constitutionalism” and the Chinese dream this year and see for yourself.) Instead, they are talking about China living up to the constitution it already has.

It would be an act of kindness to say that Yu Zhong’s piece makes an argument. Here, for example, is one of several tasty morsels of nonsense he offers up:

The history of China over the past half-century has shown that “constitutionalism” is sometimes the “English dream” (英国梦), and sometimes the “Russian dream” (俄国梦), etcetera. This shows us that the patterns and experience of “constitutionalism” are pluralistic and diverse. In different ages, under different environments, different people have different “dreams of constitutionalism”. While they are all talking about “constitutionalism,” the constitutionalism you are dreaming about in a specific time and place is possibly different from the constitutionalism they are dreaming about in their own time and place. You can see that “the dream of constitutionalism” is not a uniform, clear and specific dream.

This isn’t an argument at all. It’s a common-sense platitude — like saying, “One size doesn’t fit all!” — thrown out as a rhetorical distraction. If this were logic, we could as easily use Yu’s “argument” to undue one of the CCP’s most unassailable political concepts, “socialism with Chinese characteristics”:

The history of China over the past half-century has shown that “socialism” is sometimes the “English dream” (英国梦), and sometimes the “Russian dream” (俄国梦), etcetera. This shows us that the patterns and experience of “socialism” are pluralistic and diverse. In different ages, under different environments, different people have different “dreams of socialism”. While they are all talking about “socialism,” the socialism you are dreaming about in a specific time and place is possibly different from the socialism they are dreaming about in their own time and space. You can see that “the dream of socialism” is not a uniform, clear and specific dream.

The core of Yu’s patronizing sally is the same irrational current of cultural subjectivity that underscores much of Chinese nationalism — the warm-breasted conviction that China is special and works by its own parallel universe of rules.

The notion of cultural subjectivity comes through clearly in this passage from Yu Zhong. Comb through the bluster and you realize he’s saying one thing only, that China is different and everyone needs to respect that. Admitting China’s uniqueness and its need to assert that uniqueness as a matter of cultural sovereignty, we have to admit that constitutionalism, a Western idea, is an assault on Chineseness:

In an age of pluralism, we must see that democracy and freedom have different meanings in different language environments. Under the banner of democracy, we have representative democracy, deliberative democracy, direct democracy, indirect democracy, and other forms of democracy. Under the banner of freedom, we have positive freedom, negative freedom, and also other types of freedom. These differences in freedoms and democracies remind us that we need to see our own process of the building of democratic politics (民主政治建设) and political reform through a different and compatible way of thinking. On this question, [the famous scholar] Fei Xiaotong (费孝通) said it best: “If people appreciate their own beauty and that of others, and work together to create beauty in the world, the world will live in harmony.”

Different countries have different dreams, and the dreams of different countries should “live in harmony.” In the current language environment, we can say more concretely and directly that the Chinese dream and the American dream should “appreciate the beauty of one another.” That kind of thinking that sees the American dream as representing the “dream of constitutionalism”, and then uses the “dream of constitutionalism” to represent the Chinese dream is a kind of cultural lack of confidence and a form of “lazy thinking” (懒汉思维).

This of course is “lazy thinking” at its most refined. Political conservatism — and ultimately the repression of rights and freedoms — is couched in the language of cultural preservation.

It’s not a surprise at all, then, that section three of Yu’s article leads us into a more detailed discussion of the “confidence” that must underlie the Chinese dream.

3. Where does confidence about the “Chinese dream” come from?

One necessary condition of understanding the Chinese dream is the emergence of cultural confidence. Without cultural confidence, there is no Chinese dream to speak of. So-called cultural confidence means establishing confidence about Chinese culture and its future. What is the premise of cultural confidence? Where does confidence in the Chinese dream come from? I believe the “great history” of Chinese culture can provide support for confidence in the Chinese dream.

Yu follows with a brief discussion of the history of Chinese culture, and the two major incursions of “Western culture,” in the form of Buddhism’s arrival from India in the 2nd century, and the arrival of Western Christian culture in the 19th century. He concludes with this affirmation of the future of Chinese culture:

At present, European and American culture may seem to have great attraction, and it may seem to represent a “conclusion” or “ultimate form” of human civilization. But change is the nature of things. Fundamentally speaking, while Chinese culture may assimilate European and American culture, Chinese culture will not become a replica of European and American culture. After Chinese culture has assimilated European and American culture, it will only become richer and more inclusive, and it will at the same time have greater vitality. This is the foundation of Chinese cultural confidence, and it is a precondition for our achievement of the Chinese dream.

This notion of “cultural subjectivity,” or wenhua zhutixing (文化主体性), is at work at the heart of Chinese nationalism — which in turn is the only tangible core meaning of Xi Jinping’s Chinese dream. The dream of national rejuvenation. The rise of China in all of its glorious uniqueness.

The problem, as I see it, is that the ideology of uniqueness is being advanced in order to repress the creative instincts of Chinese society and enforce a culture of unity. For all its rhetorical lightness and buoyancy, the Chinese dream has become a political colossus. How many native dreams will Xi Jinping crush to serve this tyranny of uniqueness?

Chinese historian Yuan Weishi perhaps summed up the pitfalls of “uniqueness” as a political value best when he wrote in 2007:

If we talk grandly about subjectivity, regardless of our ultimate designs, in the end we can only be of use to champions of nationalism and we will produce ideological trash.

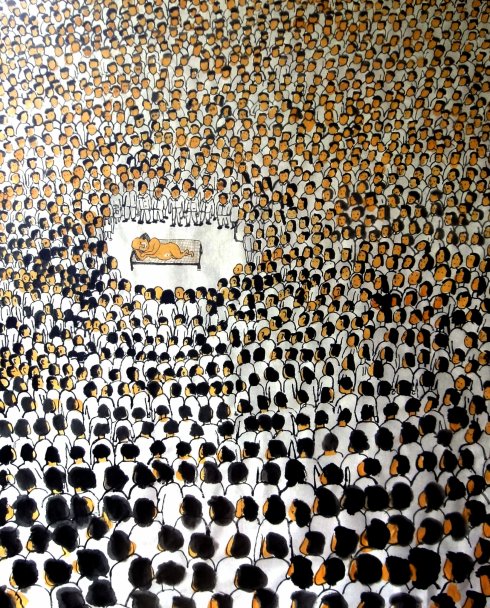

[ABOVE: In this cartoon posted to the internet and Chinese social media, the artist depicts the Chinese Communist Party as a naked man sleeping sweetly and dreaming on a bed surrounded by the masses. The cartoon asks: whose dream is this exactly?]