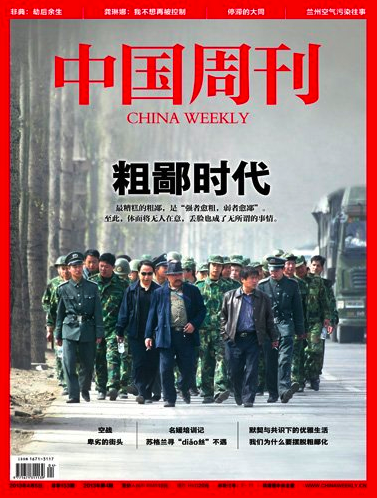

The author, Zhu Xuedong.

In the past, you could find journalists striving for professional space even against immense institutional pressures, a process that often required yielding to the second-best choice (like Southern Weekly‘s old battle-cry, that while there might be truths that could not be told, they would not tell outright lies). Now, even this instinct is lost among media leaders and editorial staff.

With experienced professionals few and far between, expedience is now the name of the game. Online rumors are accepted as “news” without any effort to confirm, fact-check or actually conduct interviews. This is so frightfully common you can even find it at well-regarded media that consider themselves serious professional players.

Our content has become homogenous and superficial. I doubt you could find any time when reporting and writing in our media was so degenerate. These days, news stories slip carelessly into snap political judgements. Even profanity is used without care.

We all know the tendency our online media have to fish for readers with the sensationalizing of headlines. We now use the term “headline party,” or biaotidang (标题党), to refer to those who practice this special form of opportunism. But even our so-called serious media can be found hyping female sexuality on the front page or in prominent headlines. There’s almost nothing we won’t do, however undignified, to attract the all-important eyeball (吸引眼球).

When an official news release came out on the “confession” of Guo Meimei, we threw professional conduct and ethics aside entirely, becoming nothing more than an attack mob. Everyone used the information in the release and not a thing more. We didn’t even bother to attempt the most perfunctory of interviews.

Have we really abandoned the high road for the low road?

There are still media in China struggling to hold on to their professional standards. There are still journalists doing their best to take the high road, pursuing truth for the betterment of our society. But we cannot deny that the travelers on that road are an ever rarer sight. Nor can we deny that the other path grows more crowded by the day.

This article is a translated and edited version of a piece appearing on Tencent’s Dajia platform on September 17. Zhu Xuedong (朱学东) was the editor-in-chief of China Weekly magazine until his resignation earlier this year. He served formerly as deputy editor-in-chief at the Information Morning Post, executive editor-in-chief at Media magazine, and editor-in-chief at Window on the South. He is now working as a freelance writer.

In the past, you could find journalists striving for professional space even against immense institutional pressures, a process that often required yielding to the second-best choice (like Southern Weekly‘s old battle-cry, that while there might be truths that could not be told, they would not tell outright lies). Now, even this instinct is lost among media leaders and editorial staff.

With experienced professionals few and far between, expedience is now the name of the game. Online rumors are accepted as “news” without any effort to confirm, fact-check or actually conduct interviews. This is so frightfully common you can even find it at well-regarded media that consider themselves serious professional players.

Our content has become homogenous and superficial. I doubt you could find any time when reporting and writing in our media was so degenerate. These days, news stories slip carelessly into snap political judgements. Even profanity is used without care.

We all know the tendency our online media have to fish for readers with the sensationalizing of headlines. We now use the term “headline party,” or biaotidang (标题党), to refer to those who practice this special form of opportunism. But even our so-called serious media can be found hyping female sexuality on the front page or in prominent headlines. There’s almost nothing we won’t do, however undignified, to attract the all-important eyeball (吸引眼球).

When an official news release came out on the “confession” of Guo Meimei, we threw professional conduct and ethics aside entirely, becoming nothing more than an attack mob. Everyone used the information in the release and not a thing more. We didn’t even bother to attempt the most perfunctory of interviews.

Have we really abandoned the high road for the low road?

There are still media in China struggling to hold on to their professional standards. There are still journalists doing their best to take the high road, pursuing truth for the betterment of our society. But we cannot deny that the travelers on that road are an ever rarer sight. Nor can we deny that the other path grows more crowded by the day.

This article is a translated and edited version of a piece appearing on Tencent’s Dajia platform on September 17. Zhu Xuedong (朱学东) was the editor-in-chief of China Weekly magazine until his resignation earlier this year. He served formerly as deputy editor-in-chief at the Information Morning Post, executive editor-in-chief at Media magazine, and editor-in-chief at Window on the South. He is now working as a freelance writer.