Headlines and Hashtags

WeChat Exposes

This round-up of Chinese Media stories, which covers the holiday period, offers us an encouraging glimpse of how social media platforms, including the super-platform WeChat, can potentially provide an avenue for writers and journalists to expose malfeasance — something we have seen far less in China under Xi Jinping than we did prior to 2012.

First, we have an expose by “Ding Xiang Yisheng” (丁香医生) that alleges that Quanjian, a company marketing various drug regimens, including cancer treatments, has cheated unsuspecting customers, mostly the poor. This follows another big WeChat story earlier in 2018 about tainted vaccines making it onto the Chinese market. Both of these stories, says one media expert, are cases of “knight-errant journalists” (新闻游侠) who were formerly with traditional media, such as newspapers, finding a way to pursue stories in the tougher media environment of the “new era.”

We’re not holding our breath — after all, our other stories here are mostly about tighter controls. But the “Ding Xiang Yisheng” is important to note.

THIS WEEK IN CHINA’S MEDIA

December 22, 2018, to January 4, 2019

➢ WeChat public account exposes a fraudulent health empire in rare investigative report

➢ Allegations by former TV host Cui Yongyuan force China’s highest court into an admission

➢ CAC launches a “special campaign” to clean up “harmful information”

➢ China’s Public Security Bureau issues fines and warnings for mobile “wall-climbing” by individual Chinese users

➢ People’s Daily and other Party-run newspapers to get page reductions for 2019

[1] WeChat public account exposes a fraudulent health empire in rare investigative report

On December 25, 2018, “Ding Xiang Yisheng” (丁香医生), a self-media dealing with health and medicine, ran a report called “The Billion Dollar ‘Quanjian’ Health Empire, and the Chinese Families in its Shadow” (百亿保健帝国权健,和它阴影下的中国家庭). Taking as its starting point the death of a four year-old girl who ended her chemotherapy treatment in the hospital in favour of an oral medication offered by Quanjian, the article reported on Quanjian and its multi-level marketing approach to the sale of what it alleged are fraudulent and ineffective treatments, with sales mostly targeted on low-income working families.

On December 26, Quanjian issued a response in which it accused “Ding Xiang Yisheng” of cobbling together unverified online accounts and information, and demanded that the public account remove its article. “Ding Xiang Yisheng” responded that it would not comply with the request, and that it invited legal action from Quanjian.

According to journalist Zhang Feng (张丰), the “Ding Xiang Yisheng” story is a bona fide work of investigative reporting, and its author is former newspaper journalist. Zhang pointed out that another of the most influential reports in 2018 had been “Vaccine King” (疫苗之王), an article posted to the WeChat public account “Shan Lou Chu” (兽楼处) that exposed problems in China’s vaccine industry, and that that report too had been written by an investigative reporter using information available online. Zhang Feng referred to these former journalists as “knights-errant” (游侠) who continued their old methods of interview, investigation and writing after moving on from jobs at traditional media. Zhang said that with the global collapse of traditional media, the era the “knight-errant journalist” (新闻游侠时代) had arrived.

Key Sources:

WeChat public account “Ding Xiang Yisheng” (丁香医生): 百亿保健帝国权健,和它阴影下的中国家庭

Tencent “Dajia” (腾讯大家): 传统媒体营造的世界已崩塌,新闻游侠时代开始了

WeChat public account “Middle Class Life Observer” (中产生活观察): 新闻游侠靠什么吃饭

[2] Allegations by former TV host Cui Yongyuan force China’s highest court into an admission

On December 26, celebrity and former television host Cui Yongyuan (崔永元) made posts to Weibo alleging that China’s Supreme People’s Court had lost key case documents in an ongoing dispute between two large Chinese mining companies. Initially, on December 27, the Supreme People’s Court issued denial of what it called “rumours,” saying the documents in question were safe. But Cui continued to pursue the issue, questioning whether the court was in fact lying about the documents. Finally, late at night on December 29, the Supreme People’s Court issued a “Situation Notice” (情况通报) in which it admitted that documents were missing and that it would conduct an investigation: “If it is determined that court personnel violated procedure, this will be handled seriously in accord with the law and Party disciplinary regulations,” it said.

The documents in question reportedly include key details of a 2006 lawsuit brought by Kechley Energy Investment against the state-owned Xian Institute of Geological and Mineral Exploration.

Key Sources:

WeChat public account “Huaxia Investigations” (华夏调查): 疑似最高人民法院法官自述视频流出:证实卷宗被盗、监控黑屏

FT Chinese (FT中文网): 从最高法院卷宗失踪案看中国的“人治”与法治

China Youth Daily (中国青年报): 崔永元说的陕北千亿矿权案到底是什么案子

Sina Weibo account of Cui Yongyuan (新浪微博@崔永元): Post 1 and Post 2

[3] CAC launches a “special campaign” to clean up “harmful information”

The Cyberspace Administration of China announced on January 4 that it would launch a “special campaign” (专项行动) from January-June 2019 to “clean up the online ecology” (网络生态治理). The campaign, to be conducted in four phases, will target websites of all kinds (各类网站), mobile apps (移动客户端), forums and message boards (论坛贴吧), instant messaging tools (即时通信工具), video streaming platforms (直播平台) and other services that disseminate 12 categories of content, as follows: 1. pornographic or obscene (淫秽色情); 2. vulgar (低俗庸俗); 3. violent (暴力血腥); 4. frightening and horror (恐怖惊悚); 5. fraudulent and gambling (赌博诈骗); 6. online rumour (网络谣言); 7. feudal superstition (封建迷信); 8. deriding or spoofing (谩骂恶搞); 9. threatening or menacing (威胁恐吓); 10. sensational headlines (标题党); 11. inciting hatred (仇恨煽动); and 12. broadcasting harmful lifestyles and harmful popular culture (传播不良生活方式和不良流行文化). The CAC said the campaign would investigate and shut down illegal websites and accounts, “effectively preventing the power of harmful information to bounce back and return.”

On January 3, CAC authorities in Beijing targeted accounts and products on Sohu’s mobile-based platform, Sohu WAP (搜狐WAP网), the Sohu News app, and certain Baidu products, calling in the managers responsible for discussions. The Sohu News app and Sohu WAP were ordered to suspend posting of new content for one week. Content suspensions were also ordered for Baidu’s mobile search engine (百度手机网页版), the “Recommendations” section of the Baidu News App (百度新闻客户端“推荐频道”), and the “Women’s Channel” (女人频道), “Comedy Channel” (搞笑频道) and “Feelings Channel” (情感频道) of the Baidu APP.

Key Sources:

People’s Daily Online (人民网): 国家网信办启动网络生态治理专项行动 整治12类有害信息

WeChat public account “Media Observer” (传媒大观察): 网信办约谈搜狐、百度,新一年整改正在进行中!

[4] China’s Public Security Bureau issues fines and warnings for mobile “wall-climbing” by individual Chinese users

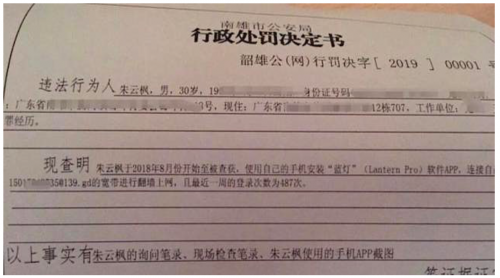

Information made public through the Guangdong Public Security Enforcement Information Platform (广东公安执法信息公开平台) on December 28, 2018, revealed that one internet user in the city of Shaoguan (韶关) had been fined 1,000 RMB for “daring to set up and use of a VPN to “access the international web.” The image available of the “Decision on Administrative Punishment” showed that the accused, 30 year-old Zhu Yunfeng (朱云枫), had installed Lantern Pro, a software application that allows open access to blocked websites and apps, on his mobile phone in order to access websites outside China, a process often referred to in Chinese as “climbing the wall” (翻墙).

Key Sources:

Guangdong Public Security Enforcement Information Platform (广东公安执法信息公开平台): 行政处罚决定书[2019]1号

Toutiao account “Moonlight Blog” (月光博客): 网民“翻墙”被罚:建立使用非法定信道进行国际联网

[5] People’s Daily and other Party-run newspapers to get page reductions for 2019

The WeChat public account “Media Observer” reported on January 3 that a number of key Party-run newspapers, including the flagship People’s Daily, Guangdong’s Nanfang Daily, and Zhejiang Daily, started out 2019 with makeovers, including page reductions and the introduction of new columns and other features.

The People’s Daily introduced full-colour printing for the first time in history, and reduced its total number of pages from 24 to 20, with the usual 12-page weekend editions reduced to just 8 pages. Nanfang Daily, meanwhile, launched a new column called “Theory Weekly: (理论周刊) with which, it said, it intended too “consolidate the high-ground of southern commentary” — presumably meaning that it wished to create a new voice on ideological matters that would showcase the ideas of the Guangdong leadership.

Zhejiang Daily, which has said it will capitalise on its advantages as “the place where the shoots of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era sprang up” — meaning that Xi was Party Secretary there from . 2002 to 2007 — has introduced several new page sections, including a “Hot News” section (要闻板块) showcasing the “most valuable news”, a “City-County” section (市县板块) introducing innovations in governance at the local level (a chance for local officials to advertise themselves?), a “Viewpoint” section (观点板块) that will deal with ideological hot issues (showcasing Party officials and their neologisms?).

Key Sources:

WeChat public account “Media Observer” (传媒大观察): 解读三大日报改版,一起看看有哪些变化